Fred Steward

The UK’s first Labour government in the 1920s was undermined by ‘fake news’. The Zinoviev letter, published in the national press at the time, was a forged document purporting to be instructions from the Communist International to influence domestic UK politics. Messing about with the ‘truth’ in politics is hardly new. Yet there are troubling signs that the populism of Brexit and Trump does have some newer features. It is accompanied with an unprecedented and brazen disdain for ‘expertise’ coupled with a loss of scruple in the propensity to use the innovative potential of ICT network platforms for the propagation of ‘alternative facts’. That this represents a new political era of ‘post-truth’ is a challenging claim which, intriguing as it is, is rather too daunting for me to try and answer in this piece.

Instead, I wish to focus on a more specific domain where knowledge interacts with politics. This is the arena of science based policy concerning the assessment and mitigation of risks to health and the environment. What does Trump’s rejection of the global Paris Agreement on climate change, and the Brexiteers’ relish to exit European institutions on medicines, food and nuclear safety signify? Is it merely contingent and collateral damage or is there an emerging existential challenge to institutionalised knowledge based approaches in key policy domains such as environmental sustainability and public health? The academic field of science and technology studies (STS) should be in a good position to answer this question. It has pioneered sociological analysis of general topics germane to the answer, including the politics of expert advice, the interweaving of knowledge and interests, and processes of epistemic contestation and consensus. This is in contrast with many of the expert actors within the domain itself who tend to address specific issues from within their own specialised fields of natural science.

Yet, STS faces some difficulty in rising to this challenge. This is primarily because the thrust of its analysis has highlighted the limitations of the ‘modern’ regime of evidence based policy rather than explained its strengths. The exclusion of ‘lay’ expertise, the hidden hegemony of specific epistemic communities, the boundary work defining distinctions between facts and values, have all received considerable attention. On the other hand, the role of academic expertise in contesting commercial interests, the power of consensus building, the role of hybrid instruments to enable societal action despite scientific uncertainty have received far less prominence.

As a consequence, we are not articulating a narrative which effectively situates the positive role of modern institutions such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the European Environment Agency alongside a discussion of problematic limitations to epistemic and social pluralism. In the old political context of a post war consensus of welfare statism, this was understandable. However, in the new virulent context of right wing populism following 30 years of neoliberalism this carries considerable risks. The desired reform of the knowledge system to express the greater epistemic and social pluralism implied by the STS agenda has only been achieved to a limited degree. A result has been that the defence against populist threats has been largely expressed through a conventional discourse of scientific authority and unproblematic facts.

The new context has certainly exposed the vulnerability of any political project which relies on ‘giving voice to the marginal’ as an adequate aspiration in and of itself. This is what has been exploited by, for example, the populist endorsement of climate denial. The populist position is of course essentially dishonest. The political character of populism is not at all about pluralism. It is about a unitary claim for representation of ‘the people’ against ‘the elite’ which obscures complexity, uncertainty and diversity. Fundamentally it mobilises scepticism about scientific authority in support of a simplistic political authority.

This is surely a threat which the STS community needs to counter. Its absence leaves the public debate vulnerable to simplistic scientism as the only countervailing voice. Despite its rhetoric the populist approach does not espouse a more pluralistic approach to knowledge and expertise. Instead it simply substitutes a new focal point of political authority over traditional centres of scientific authority. Its rise exposes the unfinished and widely misunderstood nature of STS insights into the situated, partial and contested nature of scientific knowledge and the need for policy processes to acknowledge this more explicitly and effectively. This is quite different to the displacement of expertise by selective interpretation of the ‘social will’.

Rather than a shocked retreat from this new, rather unseemly and fundamentalist public discourse we need to find different ways of intervening. The unfinished transformation of government practices for knowledge in policy needs new articulation and promotion in this new political landscape. The STS community has to draw on our shared intellectual and moral resources in order to rise to this challenge. We need to show that our pluralistic project of socially situating knowledge is quite different and opposed to the populist endeavour to displace and side-line the role of expertise.

Fred Steward, Emeritus Professor, Policy Studies Institute, University of Westminster, London

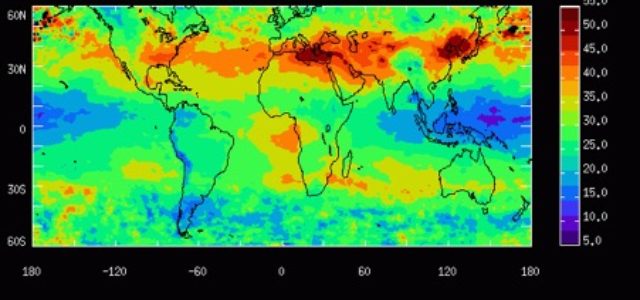

Image Credit: NASA OMI/MLS Tropospheric Column Ozone (Dobson Units)