Sebastian Möller

When I recently went to a seminar on local council borrowing in London, the horrific Grenfell Tower fire in June was one of the prominent examples referred to by speakers. This might be due to the fact that this event was both incredibly brutal and still very recent. However, it certainly also shows the connection between local finances and social housing. The crisis of the latter in the UK has not just become obvious since the Grenfell fire. British cities, and London in particular, increasingly lack affordable homes and the building condition of the social housing stock of many local authorities at best leaves much to be desired and at worst turns into a danger for the health and life of its residents. Grenfell has become an exemplar for the devastating state of social housing in this country that reminds some observers of the Victorian times when Friedrich Engels wrote his impressive ethnography on the living conditions of workers in Manchester (Chakrabortty 2017a). Irresponsible deregulation, a remarkable investment backlog, and an incredible ignorance towards resident´s complaints turned the tower into a deathtrap for at least 80 people (Benjamin 2017, Chakrabortty 2017b, Grenfell Action Group, Kirkpatrick et al. 2017).

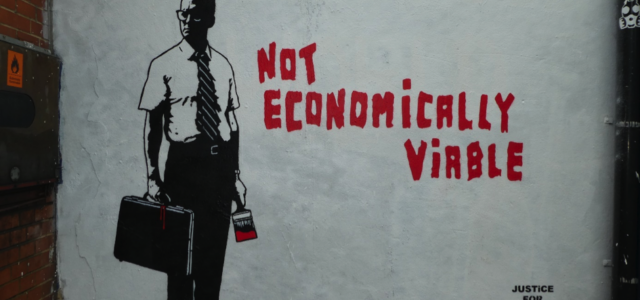

After what happened, it is of the utmost importance that the truth of the causes of this tragedy is brought to light. All actors involved in social housing provision from city councils to regulators and contractors need to learn from it in order to prevent a similar catastrophe from happening in the future. Part of this effort is that residents and neighbors in North Kensington can tell their stories and share their impressions of what has happened. Fortunately, local residents are strongly voicing their complaints and concerns. Most likely, this will reveal that Grenfell was much more than a tragic accident. Hopefully, it will also reaffirm the long-standing protests of residents across the country against the devastating state of social housing and the concerns raised by activists against the neoliberal transformation of local government.

The UK housing crisis has a long history and strongly reflects rising inequalities between the rich and the poor (de Noronha 2017). However, the persistence of austerity as a dominant policy program, certainly, has worsened the situation in the last 10 years. This can be interpreted as a further redistribution of wealth (and power). We already know that fiscal retrenchment threatens lives and sometimes even contributes to (poor) people dying (Mendoza 2015, Whyte & Cooper 2017). Grenfell, however, constitutes a new dimension of this violence of austerity. We might not yet know the full picture of the immediate causes leading to the fire and the high number of victims. We do, however, know that there are related processes of transforming social housing and local authority finance that need to be addressed in order to fully understand the socioeconomic and political environment in which this could take place. These changes in local government have resulted in marketization, a stronger affirmation of risk-taking, and new modes of governance including contractualization (Bowman et al 2015), the outsourcing of core functions to corporations or Arms-Length Management Organizations [ALMOs] (Cole & Powell 2010) and other Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) as well as privatized urban regeneration and the use of highly contested Private Finance Initiatives [PFIs] (Ball et al 2007, Froud 2003).

The London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, in which Grenfell is located, is reported to have accumulated financial reserves of £274m and to have granted tax rebates for high income residents (Syal & Jones 2017). With this in mind, it is hardly convincing that the council was not able to pay for a fire resistant thermal cladding at the Grenfell Tower. What is worse, Kensington is not a single case. Arguably, local councils, in general, are under a huge (and rising) pressure to generate savings due to cuts introduced by the central government. Simultaneously, many local authorities are engaging in (local or non-local) property investments in order to generate future income. This seems to be highly needed because, under the Coalition government, councils are increasingly put into a position where they have to rely on generating revenues rather than on redistributed money from the Treasury.

Accordingly, there have been reports on a rising trend towards councils borrowing money in order to invest in commercial property which is basically a speculation on rising values (Ellson 2017, Plender 2017). This does not only raise concerns about the proper use of public money, it also comes at a time of a systematic neglect of social housing investments in Britain. Nick Dunbar, editor of Risky Finance, has collected data on local authority borrowing. He argues that the 2012 HRA reform that was meant to help councils invest in housing actually increased the inequality between councils with high value land (usually in the south) and those with a high share of social housing (some London Boroughs and councils in the north). Clearly, there is a link between the ability of councils to borrow money and their leeway for social housing investments (how they would use the borrowed money, obviously, is another question to be asked).

However, not only has the financial situation of councils changed a lot over time but also the way in which local authorities “manage” their debt. In fact, the very idea of managing debt entered local government only in the last two decades and originates in corporate finance. It is probably not a bad thing to look for the best conditions and dates to take on loans. Citizens rightly demand a sound and prudent financial management from their councils. The transformation of local authority finances, however, is as much technical as it is political. So-called “active debt management” introduces financial market logics to public administration. It also increases the dependence on external expertise given the complexity of markets and financial products and the staff cuts in town halls.

It is, thus, no surprise that almost all UK councils are using private treasury management advisors and brokers in order to manage both their borrowing and investments. While some councils might have actually saved money, in many cases, this new way of doing local finances has resulted in unfavorable deals (and thus in the opposite of its intention). Among other factors, this is due to the heavy asymmetry of information between the public sector and the financial industry and high competitive pressures within finance that call for higher profits (which someone has to pay for). For instance, instead of taking money from the PWLB, a state agency that provides loans for councils at a rate just slightly above gilts, many councils have been borrowing from the markets. British and foreign banks were offering so-called LOBO loans to councils (and housing associations) that are not only ultra-long term but also include an embedded derivate that increased the risk of rising interest rates (Benjamin 2015, Foster 2016, Gilbert 2016, Möller 2017). If councils want to cancel those loans they would have to pay extraordinary high redemption costs. This makes it harder to replace a LOBO with a new PWLB loan at lower interest.

Meanwhile, the LOBO market has dried out on both the demand and the supply side. The campaign of Debt Resistance UK has increased the awareness of the public and within town halls. It puts the newly financialized practices of UK councils under high legitimacy pressures. However, this is neither the beginning nor the end of the story. Only a stone´s throw away from Grenfell tower lies the border to Hammersmith & Fulham, another West London Borough. In the history of British local finance, the name of this particular council is closely tied to the emergence of derivative products. In the late 1980s, Hammersmith town hall was the scene of an unseen speculation with public money: the council entered into various derivative contracts, mostly interest rate swaps, and almost went bankrupt (Campbell-Smith 2008, Tickell 1998). Subsequently, those deals were declared ultra vires and banned from UK local government. Afterwards, interest rate swaps, as an instrument of local authority debt management, moved from Britain towards the continent were their selling peaked just before the crisis and caused considerable losses for local budgets (see Lagna 2015 on Italy and Hendrikse & Sidaway 2013 on a German case). Apart from significant institutional differences, the resemblances of changes in local authority finance across Europe are quite astonishing.

Arguably, LOBO loans constitute a return of derivatives to British town halls in a new form. If you take the Hammersmith & Circle Line towards east at Latimer Road Station just down the road from Grenfell, you can observe where this return of derivatives might lead. The London Borough of Newham has not only the highest share of LOBO loans, it also entered contracts of the most risky type even after the crisis when other councils already returned to PWLB. Even after the restructuring of the loans from Barclays, Newham pays much higher interest than it would with PWLB loans. According to the Risky Finance data, Newham spends almost 60% of its council tax income on interest. Money that cannot be spend on much needed social housing investments. The council even had to make further cuts in order to service the LOBO debt. This basically transfers money from the ones that are most in need of welfare and public infrastructure to those on the other end of the ladder. What that means in practice has been shown in the Channel 4 Dispatches documentary “How Councils Blow Your Millions”.

Grenfell is located between Hammersmith and Newham in every sense of the word. Also in between are the City of London and Canary Wharf, epicenters of global finance. The geography of this transformation of local government is noteworthy and somehow in line with the distribution of wealth in this beautiful and often brutal city. Financial market logics are rapidly expanding from the City to the residential areas via new modes of local governance. But it is not only the financial industry that is driving this but also the politics of austerity and new public management pushed by central government and other state actors.

The lack of adequate financial resources for much needed social housing investments, certainly, has contributed to councils taking higher risks on the markets. Some of the poorer councils were desperately looking for capital after years of financial hollowing-out under the Conservatives and performance management under New Labour. If we want to understand Grenfell and other cases, we also need to look at financial practices of councils and housing associations. Kensington council did not engage in LOBO loans but the new (entrepreneurial) spirit of local government no doubt is at work there, too, in other ways. We might have to think of new ways to better govern a council and the respective community independently of market logics. This endeavor should include the public and academia.

Sebastian Möller is a PhD student in the Research Group on Transnational Political Ordering in Global Finance at the University of Bremen.

Image: Duncan C Flikr, under a Creative Commons licence