Jon Glasby and Rosemary Littlechild

The Policy Briefing section of Discover Society is provided in collaboration with the journal Policy & Politics. The section is curated by Sarah Brown.

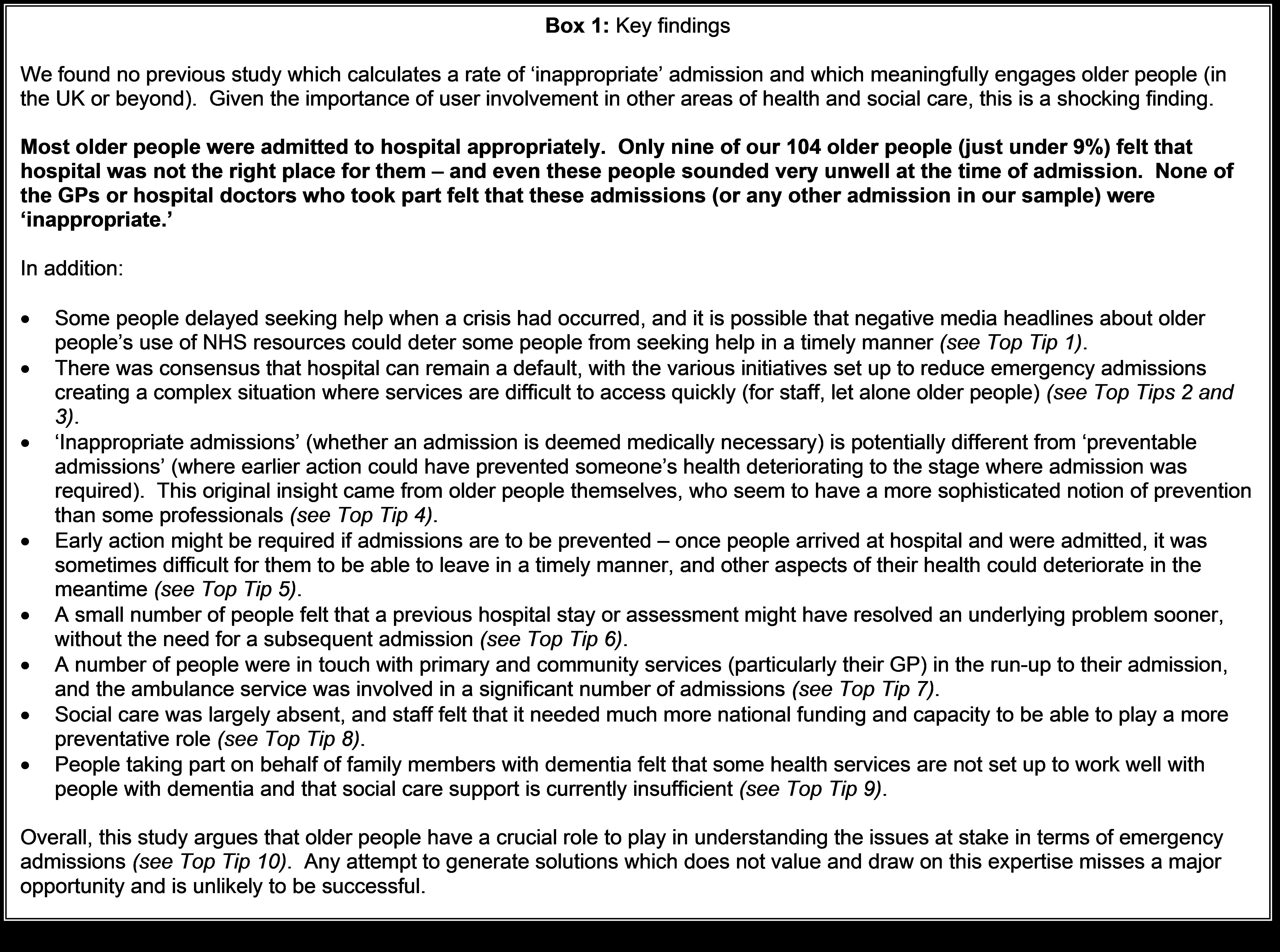

Every year, the NHS experiences more than 2 million unplanned hospital admissions for people over 65 (accounting for 68 per cent of hospital emergency bed days and the use of more than 51,000 acute beds at any one time). With an ageing population and a challenging financial context, such pressures show no sign of abating – and the NHS is having to find ways of reducing emergency hospital admissions (in situations where care can be provided as effectively elsewhere).

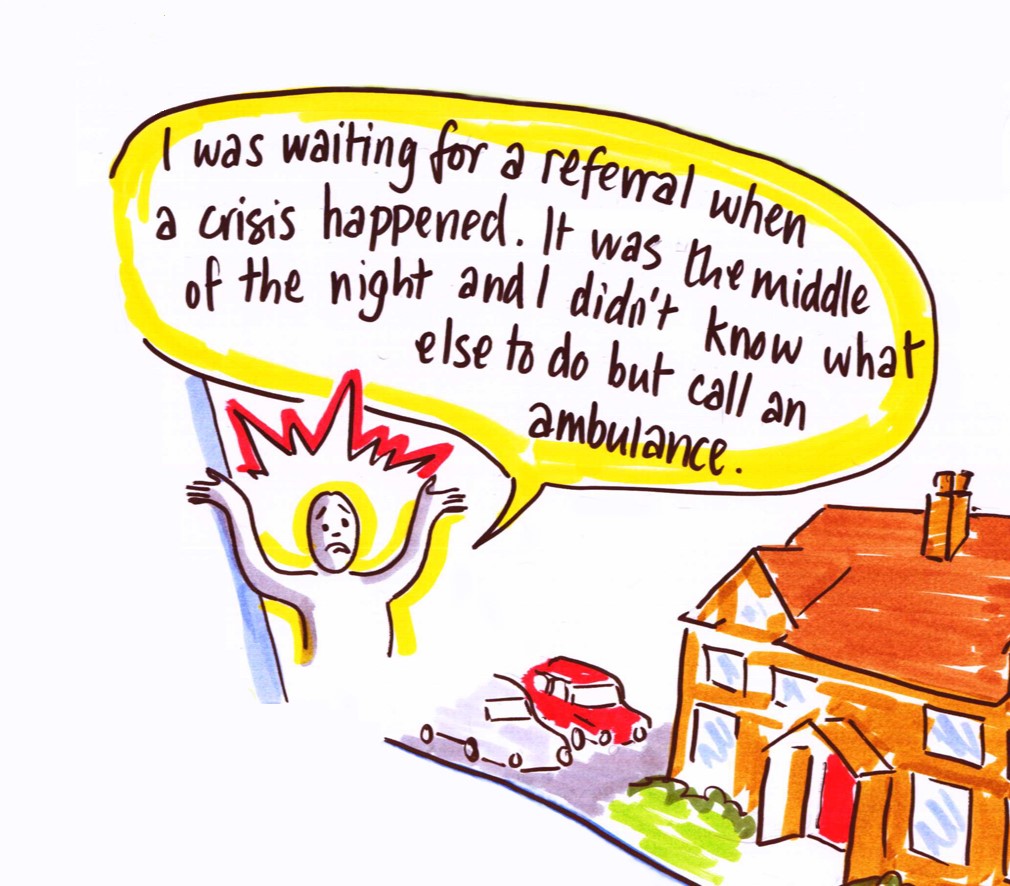

Often, the assumption in policy and media debates seems to be that potentially large numbers of older people are admitted to hospital without really needing the services provided there, but because there is nowhere else for them to go or because other services are not operating effectively. Depending on the commentator, the culprit may be slightly different – from a lack of social care to difficulties accessing out-of-hours GP care, and from the limitations of community health services to problems with 111 or the ambulance service. In earlier debates, hospitals themselves were the focus of significant blame and mistrust, with suggestions that some older people were being admitted unnecessarily to ‘game’ NHS access targets and payment mechanisms. However, most accounts are much better at identifying alleged problems than they are at exploring the detail of the claims made or proposing practical solutions.

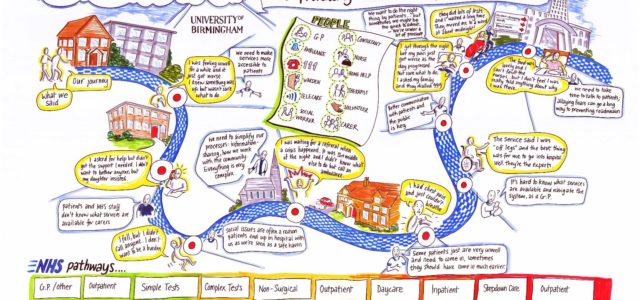

In response, our ‘Who Knows Best?’ research is believed to be the first study in the UK to explore the issue of ‘inappropriate’ hospital admissions from the perspective of older people – and quite possibly the first English-language study to do so internationally. Working with older people and their families, as well as with front-line staff, in three case study sites – our research found that most older people needed to be in hospital (Box 1).

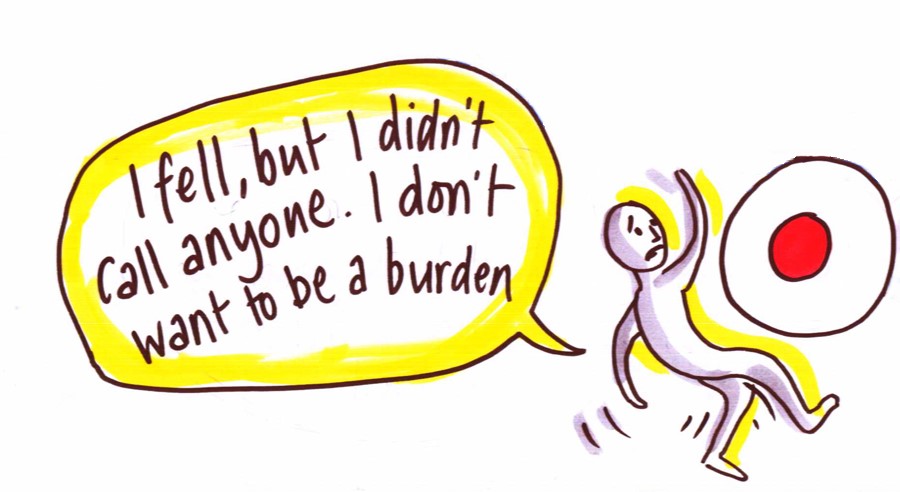

Contrary to media stereotypes, some older people may have delayed seeking help in a crisis, perhaps through a desire not to be seen as a burden on scarce NHS resources. By talking to people with in-depth

personal experience of the issues at stake, we also identified a series of broader issues that may help to improve services and to develop more preventative approaches over time. These have been captured in a national guide to good practice, which sets out ‘ten top tips’ which could only have been developed by engaging with older people themselves (Box 2).

This guide will go to every hospital, social services directorate and clinical commissioning group in the country, and is accompanied by a free online video summarising key issues for front-line practitioners.

|

Box 2: Ten ‘top tips’

|

|---|

Ultimately, we believe that older people have a key role to play in understanding and responding to the rising number of emergency admissions. While health and social care professionals can only ever know the person from the moment they walk in the front door, it is older people and their families who have a longer-term sense of how their health has changed, what response they got when they sought help and what might work best for them. Until we start to value and learn from this expertise, the contested and problematic issue of emergency hospital admissions is unlikely to be resolved.

Jon Glasby is Professor of Health and Social Care and Head of the School of Social Policy at the University of Birmingham. Rosemary Littlechild is Senior Lecturer in the School of Social Policy at the University of Birmingham. This article is based on a two-year national research project funded by the National Institute for Health Research (Research for Patient Benefit programme). In total, we interviewed 104 older people or their families within 4-6 weeks of their emergency admission and sent surveys to these people’s GPs and a hospital-based doctor (with a total of 45 responses). We also reviewed the previous literature in the UK and beyond, interviewed 40 health and social care professionals and explored the stories of some of the older people who took part in focus groups with 22 local front-line practitioners. The project was overseen by a national ‘Sounding Board’ comprising: Age UK; Agewell; the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services; the NHS Confederation; and the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE). A ‘Social Care TV’ video summary is available from SCIE and the full report and a national guide to good practice will be available via the University of Birmingham website (see here and here).