Mehita Iqani

Often lambasted for their supposed political indifference, labeled by their parents as apathetic, lost, or shamefully materialistic, South Africa’s generation of “born-frees” (those born after 1994) has proved in the past weeks that they are conscientized, politicized and capable of powerful forms of united mass action in service of social justice. In the past weeks, university campuses across South Africa have seen a variety of protest action – most of it entirely peaceful – including blockades of campuses, marches to and assemblies outside of key sites of decision-making, and the occupation of university buildings.

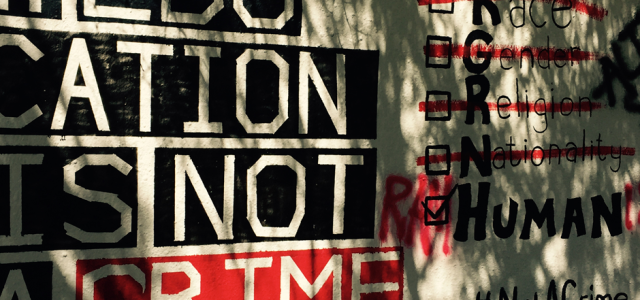

Building on April’s Rhodes Must Fall movement at the University of Cape Town (UCT), in mid-October students at Johannesburg’s University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) mobilized to protest against a 10.5% increase in tuition fees for 2016, using the hashtag #FeesMustFall. But as many have pointed out, the movement was about much more than the high costs of fees. The student movement vocalized huge dissatisfaction with the marketization of the university system, the failure of government to provide the free education that was promised in 1994, and the exploitation of the lowest paid workers on university campuses through outsourcing.

The success of the student movement is hard to overstate. In just over two weeks, it effectively shut down 14 South African university campuses for varying lengths of time, influenced the national government to decree that there should be no increases in fees for 2016 and to commit (rhetorically at least) to investigating how to provide free, quality education to the poor. They also succeeded in convincing university vice-chancellors at UCT and Wits to commit to ending the practice of outsourcing, which has been in place for a decade and a half. Outsourcing is the policy of re-locating jobs, usually the lowest-paying, on contract to external companies, rather than keeping them within the sheltered environment of institutional employment.

Student protestors faced police brutality, indifference from politicians, and were – in the beginning of the movement at least – largely misrepresented by mainstream media outlets. Yet they remained focused, committed, peaceful and energized. Although some micropolitical schisms and skirmishes broke out as the tide of the revolutionary spirit ebbed as new successes were achieved, and on all campus the student movements are fracturing as party-aligned politics re-emerges, in the main the movement was distinguished by its sense of united moral purpose.

By making their demands, students have forged a new form of politics in post-Apartheid South Africa. It took today’s hashtag generation to show up those in power – those running governments and universities – for their failure to deliver on the promises of opening the doors of learning for all. The petition of the student movement was simple: develop a new funding structure for higher education. Harking back to scenes of striking schoolchildren and students in 1976 and images of smartphone-wielding youth leading a revolution in Tahrir Square in 2011, the spring of 2015 has witnessed masses of young people facing teargas, private security forces and rubber bullets to make their views heard and achieve real change – tweeting all the while.

Why did students protest? Because of devastating financial exclusion suffered by academically deserving students from poor, black families. No matter how excellent their academic performance – already often compromised by the many obstacles that poverty places in their way – students who do not have the means to pay are repeatedly denied access to university. Most institutions in South Africa – especially the best – require payment of a massive upfront fee before registration each year. Moreover, students are routinely and dispassionately kicked out of their programs or denied access to their grades if the fee accounts are not settled by the end of each year.

Students testify to the huge implications that these policies have on families already struggling to make ends meet. For poor families, putting a child through tertiary education is not just a question of individual prestige. It is a matter of social mobility and a better future. Parents, who have been stuck in menial, low-paid labour all their lives, as a direct result of Apartheid and its legacy, put all their hopes into the next generation. They trust that their children, degrees in hand, will be able to access a better paying jobs and thereby help to lift entire families out of poverty. Graduates from poor families who make it through the system carry huge responsibilities for extended families. An inability to pay fees leaves families’ dreams of a better life in tatters. All of these issues were taken on by #FeesMustFall protestors, with varying results. At Wits, where I teach, after intense, long negotiations an agreement was finally reached that addressed some of these issues: for example, students owing R15,000 or less will no longer be prevented from graduating.

Despite the many successes achieved by the student movement, the bigger question remains on the public agenda, and will surely spark sustained action and engagement in the future. Why do South African universities, institutions statutorily constituted as public, charge fees? Especially when one of the election campaign promises of the African National Congress in 1994 was free quality education for all? This is precisely the question that thousands of students forced everyone in South Africa to ask during the past weeks. Professors and policymakers argue that tertiary education has been grossly underfunded by the state since the democratic government took over. Quite simply, because of reductions in government contributions, universities have tried to make up the shortfall through fees.

Add to this the rise of a mangerialist, corporate logic in the running of educational institutions, where the lowest-paid workers are outsourced to save money (while management pay themselves high performance bonuses), and a mal-administered national scholarships programme, and you have what David Dickinson, Professor of Sociology and a member of Council at Wits, calls “an explosive cocktail”. Although students used #feesmustfall to access the national spotlight, what they are fighting against is a broken system that displaces the financial responsibility for tertiary education on to those least able to shoulder it. As one student tweeted, “Broken hearts and broken bones from a broken leadership structure filled with broken promises leaving us with broken dreams” (@Bobo_Motsoane). Considering that the South African government routinely spends huge amounts on arms procurement, new road toll infrastructures, private jets and bodyguards for officials, its under-spending on higher education begs at least critical analysis, and at most, a revolution.

And it was youth of today that spearheaded that challenge to the government. Inspired by a student leadership united across political affiliations, including some very high-profile women, the current student movement reinvigorated politics and provided a principled challenge to the ANC’s failure to deliver on its promises with regards to opening the doors of learning to all. They also achieved massive successes in a short time period: no increases on fees for the immediate future, turning the public spotlight on to the urgent need for the government to respond to the higher education funding crisis, and forcing out the exploitative practices of labour outsourcing on university campuses. Despite having been initially criminalized by their own universities, attacked by police on their own campuses, arrested and even allegedly charged with treason (charges that were later dropped), seeing the ANC itself try to co-opt the cause, and experiencing some fractures in organization and leadership, the Student Spring of 2015 remained disciplined and convincingly claimed the moral high ground away from those in power.

Ironically, those sitting in parliament, Luthuli House, and the Union Buildings upon which students have marched were the youth of 1976, fighting for the right to learn on their own terms. They were forced to hear the same message from today’s revolutionaries. But did they listen? What remains to be seen is how the legacy of 2015 will translate into ongoing reform in South Africa’s higher education sector in the long term. If the past weeks are anything to go by, this is not a struggle that students will easily abandon.

Read a statement from South African academics calling on the government to restructure its higher education funding here.

Mehita Iqani is Associate Professor of Media Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand.