Steve Hanson

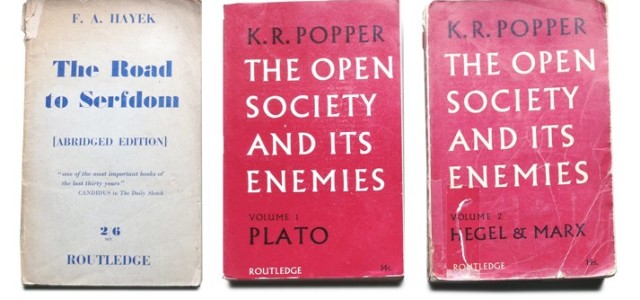

A few years ago, I was given some books. Among them was a 1946 edition of F.A. Hayek’s The Road To Serfdom, a ‘liberal’ right-wing intellectual, whose ideas were eventually championed by Margaret Thatcher, informing her 1980s policies on free market monetarism, coupled with a weakened state.

I felt that this book was a kind of gauntlet thrown down. I approached my reading with an internal deep breath, an ‘OK von Hayek, convince me’, before taking the plunge…

Previously, and only semi-consciously, I had feared dipping into relatively right wing texts, in case I became even partly converted. Infected, even. But actually, reading on the right is a great discipline, and I want to champion it here. Reading Hayek, I quickly realised that my combative entry into his text wasn’t fully applied to my reading ‘on the left’.

Put more simply, I wasn’t entering into work by writers I lazily assumed to be ‘the goodies’ with anything like the same wariness I applied to Hayek. But rather than turn me into a neoconservative apologist, this experience actually fortified my resolve. It showed me the weaker spots in the walls of pre-Thatcher political theory, but more importantly, it made me realise that my reading on the left was lazy. It was flabby and needed to get back into training.

This isn’t a new argument. For example, Les Back asks PhD candidates to read more ‘promiscuously’, and the general conundrum can be traced right back through Orwell.

But I want to restate the point for the present moment, because reading on the right strengthened my general engagement as a reader. By extension, it shaped me as a writer. The mental, two-way conversation going on in my head when I entered Hayek’s text was much more lively than what was going on when I swallowed that last bulky essay by Jameson whole, simply because I thought I ought to.

Reading Hayek was a pivotal moment. I began to interrogate left wing texts much more critically. This didn’t turn me into a right wing apologist, it made my thinking more supple and strong. Some left wing fluff did get taken to the charity shop. I won’t go into specific titles here, but a much more rigorous weeding of my library followed. This was a good thing. The Hayek eventually got chucked out too.

It’s also worth pointing out that I’m uncomfortable with the lazy, horizontal, geographical allegories of political affiliation. When people begin to designate ‘the left’ and what ‘it’ should, shouldn’t, might or might not do, I see only that thinking has gone one level too macro to be useful. We need to bear in mind what is actually assembled behind our words. Words that already only very crudely designate the things that we want to describe.

Not long after reading Hayek, I met up with an ex-colleague from my days teaching in art schools. It was a Saturday afternoon. We sat down in the pub, and I noticed the branded Salmon pink colour of the Financial Times peeping through a leafy head of celeriac, tin cans, and the rest of his weekly shop.

Surprised, I asked him why he bought the FT. He pulled it out of his carrier bag and slid the monthly colour supplement out, which is called ‘How To Spend It’. He turned to a page of gaudy consumer knick-knacks, watches, wallets and earrings, underlining their prices with his index finger. I’ll spare you the equally lavish expletives, but he then said something like, ‘these people don’t do irony, they don’t feel they need to.’

This Saturday, I bought the FT. There are adverts for bespoke tailors, but also bespoke yacht builders. A wristwatch for £41,150 here, a purse for £2,485 there and a pair of earrings for just short of four grand.

My friend still sends me articles in the post from the FT, often selected because their political views are surprising. I remember Brian Alleyne being unfairly harangued by a naive activist, in his lecture series on global risk, at Goldsmiths, in 2003. Brian’s response was to very politely ask if this ‘radical’ ever read the financial indexes. He didn’t.

In this Saturday’s FT, a column by Jonathan Ely called ‘Serious Money’ is titled ‘Corbyn victory could lead to painful outcomes.’ The front page flags this article up, enticing readers in, by promising to tell them how ‘Corbynomics’ might hurt their wallets.

Ely, it’s safe to say, isn’t a socialist. I read through his article carefully, and as he approached Corbyn’s claim – that austerity was a choice, rather than a necessity – my stomach began to tighten for the ideological punchline. But it suddenly relaxed, as Ely, it turns out, wholly agrees with Corbyn on this point. In fact, he goes even further, stating that austerity probably didn’t help economic recovery one bit. So here was a neoconservative – and his approval of the current state-capital balance clearly make him one – telling us that not only does austerity hurt ordinary people, it probably doesn’t help capitalists either.

Austerity, for Ely, is a punitive, cultural measure, and he cites the Legal & General CEO who described it as ‘a policy by the rich, for the rich.’ Ely then goes on to criticise the system of encouraging buy-to-let landlords, siding strongly with Corbyn’s policy on the issue, negatively describing the future ‘rentier economy’ we are sliding into, and critiquing Britain’s obsession with home ownership.

The point I want to make here is not that we should be surprised that Ely holds such views, we shouldn’t. Nor should we start to imagine that he is a socialist in disguise, he clearly thinks that a lot of Corbyn’s emerging policies are ‘bonkers’, and uses that heavily loaded term in his article.

But I think we should be very surprised by the amount of left wing people claiming to be ‘intellectuals’ who don’t ever expose themselves to this kind of material. The amount of people from within my own social media networks who are completely oblivious to these discourses, I do find surprising.

If you looked at my Facebook and Twitter feeds right now, you might think the revolution had arrived. It has not. Many people don’t even realise they are in their own echo chamber, one constructed by language. There are still others who don’t realise that there are discourses which they aren’t aware of.

Back in May, an FT columnist described giving advice at a Secondary School, as part of the Speakers for Schools programme, telling them to find someone rich to live with, to then work below the threshold after which benefits are capped, in order to save money towards a deposit for a house. Here was the logic of Benefits Street inverted, its exact dialectical flipside, as it suddenly reappeared as perfectly moral advice for young upper middle class people setting out in the world. Did the mythical ‘left’ jump on this article and expose it? No.

To be fair, you can’t just grab these FT articles. They are stashed behind a pay wall. But the Guardian is so fluffy these days. The parts that I actually read would fit on to a single broadsheet. You may as well buy the FT, every once in a while, and learn to understand the indexes as well as you can.

Leftwing intellectuals need to read on the right much more urgently than they need to read the ghastly Morning Star, with its masculine, industrial worker tabloid format, loud headlines and sport at the back. The newspaper is not an envelope. It doesn’t simply empty untainted information into your head. Its form is an inextricable part of its information. Its form is content. Leftwing newspapers, at this point in history, should look like a crack in the fabric of the universe. The technology is there, the means of production and a surplus army of creatives bursting with ideas.

At the start of 2014 I began a group called Manchester Left Writers, in order to work on leftwing writing, with others, in my home city. My urge to do this partly began by reading on the right. We collectively wrote a piece called ‘The State of Scripts’, which examined some ‘symptoms of bad writing’, operating across contemporary ‘left’ academic discourses. We then satirically listed elements of these ‘scripts’, that so-called ‘radical academics’ fall back on when not utilising the full potential of their resources in the here and now.

Scripts are all resources from the past. Scripts are always half bad style and bad meaning, ruts of lazy thinking that have congealed into dead literary-academic modes, underwritten by little brackets, containing the famous names and biblical page numbers of the Harvard referencing system.

To reoccupy the present and future, actually, physically, and politically, we need to recalibrate leftwing writing so that it is symbolically fit for the scale of the task. Scripts are not about exploring the representation and politics of life in the present, in a new, risky or tentative way, because what is being produced has not yet been tried, and so is a little frightening. Scripts are about making ego-capital. A big part of this problem is that ‘leftwing’ writers often only read leftwing texts.

Despite all this effort, Manchester Left Writers received some curious comments from readers, asking us what our class credentials were, and if we were involved in trade unions and campaigns. Many of us were and are, but the idea that a group that was formed explicitly to examine and produce writing needed such qualifications seemed strange. Some of them asked why we didn’t deploy particular words, ‘socialist’, or ‘class’, for instance, much more frequently.

This immediate assumption that we fall back on the tropes of leftwing rhetoric, or die, is crazy. The demand that anyone using the word ‘left’ requires an unbroken heritage of working for trade unions, campaigns or protests, this demand for proof of a chest-beating working-class northern ‘authenticity’ bordering on cultural ethnocentrism, is dubious. It is actually quite difficult to find this kind of narrow cultural ethnocentrism in classical laissez faire neoliberal writers. This depresses me, not because I want them to be easier targets, but because I want many leftwing writers to wake from their slumbers.

When someone starts designating ‘the good socialist’, or starts to ask for solid working class credentials, as when someone starts calling ‘the left’ a thing, all useful thinking has ceased. None of this is to say that class no longer exists, or that socialism isn’t worthwhile, or any of that hideous postmodern rubbish. But ‘the left’ is still gazing into the opiated magic lantern show of its own past, its ‘glorious lineages’. The best thing it can do is to see them as broken and pick them up, and that seems to be happening, but in a notably retro-looking manner. At the same time, the right carry on dismantling it all. For five years, maybe even a decade. Labour may have a new leader, but its MPs were hammered at the last election.

That Keir Hardie began the Labour Party in Scotland is serendipitous, given that it may yet be written into history as extinguished there. Like many others, I hope that only the neoliberal Labour party was extinguished in Scotland, not the party per se. It is in no way clear what the outcome will be, yet to read some of the more exuberant monologues floating through the air, you could be forgiven for thinking it a done deal.

This is largely because so many leftwing-aligned writers remain in their bubbles. All those blogs full of blue plaques, suffragettes and dead trade unionists. Pictures of Keir Hardie, with glowing tributes, many editing out his troubling comments on migrant labour. It makes me feel exhausted. I am being provocative to make a point here, because all that history is crucial, of course, but when it becomes the sole focus, there are problems.

And we can go back here, to Marx’s 18th Brumaire, and the ‘mensch’ making their own history, but out of pre-constructed discourses, the ‘dead weight’, a ‘nightmare’ weighing heavily on the brains of the living. It isn’t an actual weight. It is language, and part of that language problem is bad reading.

This said, the dead weight of language is always so heavy that it is impossible to lift, so high that you can’t get over it, so wide you can’t get around it. My second book, then, will be offered as critical theory for the humanities, but it is a re-collage of ancient ‘scripts’, which acknowledges the inevitable saturation of the past, and revels in it, while refusing to fall back into the deep, sunless, airless dead ruts of what currently passes for academic writing. But the point to make here is that all of this partly began by reading on the right.

Ask yourself, having got this far into my article, are you one of its targets? I can hear the shrieking already, ‘how dare you reify “the left” as not reading on the right!’ Well, some people do, clearly, myself, a couple of my friends, and Brian Alleyne. But informal discourse analysis makes me sure I’m right to say that many others don’t.

I was openly mocked at a recent conference on a key leftwing writer for having the FT in my bag. My reply was a paragraph length factory floor language version of this piece.

But I am perhaps making some big assumptions about the political allegiances of my own readers. I want to invert that too, and suggest that if you consider yourself rightwing, liberal or ‘centrist’, that you should read on the left occasionally as well.

Not so that we might all get along better, or that some new middle way might open, like a blissful third eye in our political foreheads, but so that we might understand each other’s stances in detail, and that we might then argue more, and better.

Notes:

Back, L. (2007) The Art of Listening. Oxford: Berg.

Ely, J. (2015) ‘Corbyn victory could lead to painful outcomes’ in the Financial Times, Sep 19.

Somerset, M. (2015) ‘Work 16 hours a week and have rich relatives’ in the Financial Times, May 29.

Steve Hanson works as a lecturer, writer and researcher. His first book, Small Towns, Austere Times, was published by Zero, in 2014. His second volume, A Book of the Broken Middle, is currently being finished for Repeater. He has taught at Goldsmiths, in the Sociology department, at MMU, the University of Salford and the University of Lincoln. He has worked as a research assistant for the University of Oxford and central government, and as an ethnographer for City University, and LMU, in London. He has written widely for publication, including Cultural Studies, Visual Studies, Open Democracy, Street Signs, Social Alternatives.