Jodie Pennacchia

Education stood out as a controversial policy area for much of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition government. Under the leadership of Gove, change was volatile, emotively framed, and highly contested. Gove attracted extreme responses from educational stakeholders and commentators. Whilst Toby Young praised his work, Twitter was rife with furious teacher commentary on his ‘World buffet’ approach to policy making. Ahead of the 2015 election Cameron sought to quell some of this controversy, aiming to woo teachers by replacing Gove with the less contentious Nicky Morgan. Morgan has remained in post throughout the first 100 days of Cameron’s majority Conservative Government, but so far little has materialised to separate her education policies or discourse from those of her predecessor.

This is certainly the case for academy schools, which are the focus of my doctoral research. My work concerns the original and ever-present strand of this policy that aims to transform the fortunes of historically ‘under performing’ schools in communities facing economic and social challenges. This has been a key element of the policy since its launch in 2000, and has been seized upon by successive governments as a way of harnessing public support for a policy that is plagued by ambiguous and negative research. This strand of the policy has appealed to politicians seeking to market academy status as a tool for social justice. It purports to tell a compelling story of academisation ‘saving’ children in poor schools and communities from the intergenerational curse of low aspirations and educational standards.

In the build-up to the General Election a couple of things emerged as particularly noteworthy in the Conservative government’s approach to this area of policy. First we were told that the focus on so-called ‘failing’ schools would continue, but with a renewed zeal. Morgan reminded us that academy status is the main route to solving the problem of school failure, and that, under a majority Conservative government, the ‘academisation process’ would be called upon more often and implemented more quickly in order to ‘transform’ more schools into high achieving institutions. Second, that celebrated figures from the academy movement would be parachuted into these ‘failing’ schools so that those who have made academy status work can share their wisdom with less successful schools.

The first of these policies has materialised. The Education and Adoption Bill has indeed reinvigorated the long-standing link between academisation and the turnaround of ‘failing’ schools. The key change here is that the democratic processes through which school staff, pupils, parents and members of the community can challenge academisation can now be bypassed. The rationale for this, Morgan argues, is that these processes are slowing down the saving of schools, which means children spend longer being educated in ‘failing’ institutions. These democratic processes, it is claimed, are getting in the way of the social justice that academisation aims to bring about. Democracy is, in this version, repositioned as bureaucratic, as red tape, as stifling social justice.

The second of the proposals – to parachute academy super-heads and super-teachers into failing schools – has not yet materialised. However, if we consider the number of individuals who have emerged and been promoted as educational heroes through the academies programme it is a fair assumption that this is a policy that may resurface at some point over the course of this government.

Thus, it seems that shifts in the first 100 days of Cameron’s government – both in actual policies and in discourses about policies that may be coming – amount to a continuation of existing narratives about ‘failing’ schools in more economically disadvantaged areas of the country. The focus is on the ‘transformation’ of these schools through academisation, which is presented as a tool to fight educational inequality. In this way the Conservative Government continue to use the policy to capture and reframe the discourse of social justice in education.

Incorporated into the academies narrative is the assertion that poverty is not an excuse for educational failure. This powerful idea has been seized on by successive governments as a way of censoring schools who draw on poverty as part of their analysis of student performance. The inherent contradiction is that academy status is being sold as a tool for fixing the educational challenges that may be heightened in contexts of poverty, whilst also espousing a rather hard-lined narrative about not using poverty as an excuse for poor performance. In promoting the merits of school-level autonomy, what the academies policy has often done is increase the responsibility of particular schools to compensate for a wider set of social and economic challenges. These challenges have their roots in the wider social policy sphere. Moreover there are interesting symmetries between education policies and discourses – academies being a pertinent example – and the assumptions that underpin a range of other narratives that are flourishing under a Conservative administration across public and welfare services.

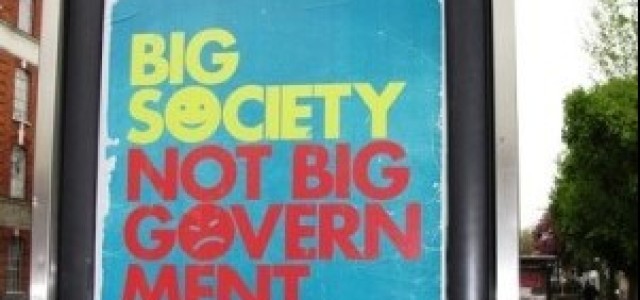

Here I am talking about narratives that position those living in poverty, and the services that work to support them, as lacking. These narratives are underpinned by an ideology that is tough on what it perceives to be ‘failure’, which has amounted to being tough on people living in poverty. Across them we see a demand for people who are struggling to take greater responsibility for themselves and for their fortunes. It is part of the Broken Britain discourse, which continues to bubble away as an underpinning thesis of Conservative public sector and welfare reforms. This is a discourse that has painted young people as feral, immoral and in need of ‘tough love’, communities as deficient, and the schools that serve them as failing.

What I have found inspiring through the process of researching academies is the vehement rejection of these discourses by the school staff I have spoken to. My doctoral research will present a critical policy study of academies through a combination of discourse analysis and ethnographic fieldwork in a school and its local community, which are facing complex economic and social challenges. I want to highlight the forms of resistance that are taking place around the narratives of lack that are being perpetuated by the new Conservative government, which have a strong presence in the academies programme.

At the same time I do not want to underplay the power of these overarching narratives on the work of schools in challenging contexts. Schools labelled as ‘failing’ that are turned into academies to improve are under immense pressure, particularly when this improvement does not come quickly enough. Amongst other consequences, this context is putting pressure on community-orientated work, which is vital in those places that have been hit hardest by austerity.

For those of us interested in education policy, the example of academies reminds us that our analysis should not remove schools from the wider political and social contexts in which they operate. Instead, schools are intimately linked with the wider set of stories that are told about social policies, and those affected by them. It reminds analysts of social policy to step back from time to time from their focused areas of study to consider how these relate to wider ideologies, and the narratives that sustain them. There is an important role for policy analysts to provide individual and joined up critiques and understandings of policy narratives. In shifting the level of analysis we take, we can open up new ideas and lines of argument in our work. In understanding the way different policy areas speak to one another, we can create more opportunities to question and challenge, in more coherent and joined-up ways, the stories that are told about the people most vulnerable to the impacts of austerity, and those who work to support them.

Jodie Pennacchia is a Doctoral Researcher in the School of Sociology and Social Policy and the School of Education at the University of Nottingham.