Ian Sanjay Patel

Much fanfare has accompanied the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta this year. For Prime Minister David Cameron, the Magna Carta marks the beginning of ‘guaranteed access to justice’ in the ‘law of the land’. Yet what can we learn about the Magna Carta, and English law as a whole, by going back into imperial history? What happened when English law and the principles it supposedly embodied were enforced on India?

English law and the Magna Carta

Historically the Magna Carta was the first in a series of instruments that asserted the right to ‘due process of law’. It is closely associated with habeas corpus (literally, ‘you may have the body’), which was designed to ensure detainees are presented to a court and thus protected against arbitrary detention. Colonial administrators, orientalists, and politicians such as Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859) maintained a righteous idea of English colonial justice in the face of its actual effects on colonized societies. Macaulay had a keen sense of English lawfulness and celebrated the Habeas Corpus Act in his History of England. Certain received ideas about an intrinsic English liberty and lawfulness continue to thrive in our understanding of Britain’s imperial history. As Dominic Sandbrook wrote recently in the Daily Mail, that the British empire ‘stands out as a beacon of tolerance, decency and the rule of law’.

In fact, the gap between the supposed equity and fairness of British governance under common law and the violent realties of colonial rule was terribly conspicuous. As Indian nationalist Bal Gangadhar Tilak put it in 1907: ‘The goddess of British Justice, though blind, is able to distinguish unmistakably black from white’.

The first writ of habeas corpus was issued in India as early as in 1775. But this much-celebrated legal principle rarely benefited the lives of countless colonial subjects over centuries of imperial rule. As evidenced in the Aliens Act, passed by the imperial parliament in 1793, non-British subjects and particularly non-European subjects were deemed in themselves a threat to the safety of the state. Not only were non-European subjects denied the King’s protection under law, their ‘foreign allegiances’ and racial ‘savagery’ were considered inherently threatening.

British rule undermined the writ of habeas corpus in India by deferring to the Governor-General’s discretion and by introducing parliamentary statutes that restricted judges’ ability to grant habeas corpus writs. Colonial governance, working according to a jurisprudence of emergency, demanded first and foremost that non-Europeans could be detained as threats to national security, however cogent their legal claims to protection.

The Indian revolutionary activist Bhagat Singh is today revered as a martyr of the Indian independence movement. In 2008 a bronze statue of ‘Shaheed [martyr] Bhagat Singh’ was erected in the Parliament of India in Delhi. He was hanged in 1931 on charges of murder, conspiracy, and ‘waging war against the King’. Applications for a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of Bhagat Singh were rejected up to two days before his execution. His death warrant had been issued after a Special Tribunal had decided Singh’s fate as a matter of national security in which the normal processes of law did not apply. On appeal that the death sentence and trial of Singh were illegal under ordinary law, the Bombay High Court averred that national security trumped individual rights, particularly in cases of revolutionary resistance: ‘The Governor General may, in cases of emergency, make and promulgate ordinances for the peace and good governments of British India’.

Bringing English law to India

Law has always been central to the self-perception of nation states. The characteristics, real and imagined, of English law and the ‘rights of free-born Englishmen’ were crucial to the legitimacy and rationale of British imperialism. Law was a pillar of British imperial governance in the colonies as well as a justification of imperial rule in the metropole. Because of the conquests of the British Empire, English common law is the most common legal system in the world, used in some 27% of the world’s legal jurisdictions. Under the pretence of bringing ‘legality’ to ‘Orientalism despotism’, the British deepened and maintained its hold over conquered and subjugated populations, principally in India. As English lawyer James Fitzjames Stephen (1829–1894) wrote regarding colonial subjects: ‘Our law is in fact the sum and substance of what we have to teach them. It is, so to speak, the gospel of the English, and it is a compulsory gospel which admits of no dissent and no disobedience’.

Until the eighteenth century in India, Islamic law and locally based Hindu law (including the iniquities of the Hindu caste system) had been in place for centuries, with many local customs stretching back to ancient India. Beginning in the 1600s, Britain began its intrusion into India via the profiteering of the East India Company (EIC), which was a wholly commercial outfit. For about a century and a half, the EIC made steady gains in political and military influence. By 1757 this commercial venture commanded almost total military dominance, and by a relentless logic of expansion now took on the enormous project of colonizing India.

For the British, the legal system of a colony and the necessary economic conditions to maximize profit were intimately connected. The Permanent Settlement Act of 1793, for example, provided the early colonial state with a legal mechanism to collect land revenues. The legal system was a natural terrain on which commercial ambitions and, eventually, the outright economic domination of India, could be realized. For example, despite stalling direly needed famine relief in the Deccan plateau, the Anti-Charitable Contributions Act of 1877 prohibited ‘at the pain of imprisonment private relief donations that potentially interfered with the market fixing of grain prices’.

The violence of English rule of law

Bringing ‘rule of law’ to the colony meant in reality the suspension of habeas corpus, the declaration of martial law, massacres, mass detention, and countless everyday acts of racial violence by white settlers. The manifold violations of colonialism, from torture to land grabs, were justified within a legal framework as so many necessities and exigencies of state governance during conquest.

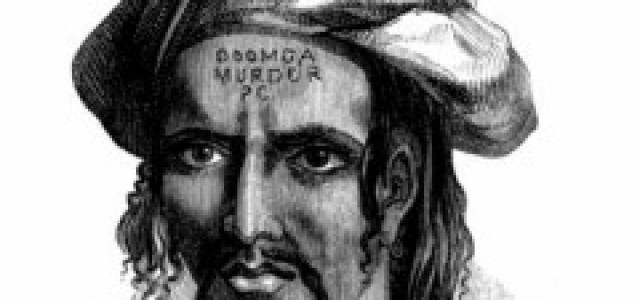

Under the empire’s rule of law, the British colonial authorities introduced penal tattooing (godna) in 1789 (see image at head of article). The godna penal tattoo was both a surveillance device and act of punitive shaming, etched on convicts foreheads in Bengal and Madras presidencies from the late eighteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries. Typically, a convict’s name, crime and place of conviction were permanently incised. Unsurprisingly, the dispensation of colonial law was starkly racialised.

The Criminal Tribes Acts (firstly in 1871, with subsequent later Acts) empowered local governors to declare as a ‘criminal tribe’ any group suspected of hereditary congenital criminality, such as the thuggee, a criminal class constructed by the British. The Acts were first applied to the North West Provinces, Awadh and Punjab, before being expanded throughout India. A governor’s judgment would by itself be taken as ‘conclusive proof’ of collective guilt, and ‘no court of justice shall question’ subsequent punishments. Punishments included life imprisonment, death, or removal to a ‘reformatory settlement’ such as the Andaman Islands, often with the word ‘thug’ (in English) permanently inked on convicts’ foreheads or cheeks. Of 3,849 defendants charged with thuggee offences between 1826 and 1841, 460 were sentenced to death, 933 to life imprisonment, and 1,504 to transportation overseas. By the time Britain was forced to leave India in 1947, over three million men and women (including children) were subject to ‘criminal tribes’ legislation.

Social functions of English law in India

Law was a particularly useful vehicle since it was able to achieve the same end results as physical conquest with less expense by using deceptively pacifying symbols of justice. British law and colonial rule were not simply about occasional uses of overt power but operated too at the level of daily Indian life, containing social, moral, and religious forces that might inhibit the colonial project. The so-called Hasting’s Plan rested on the assumption that local customs and norms needed to be incorporated into a British legal structure that was regulated by ‘universal’ – that is to say, English – principles of law. It was at this time that prominent Orientalist Sir William Jones (1746– 94) offered to conduct a ‘complete digest of Hindu and Mussulman law’. The British transformed the Hindu caste system into a rigid legal taxonomy in which Brahminical norms and texts were consolidated as superior. The modern political categories of Hindu and Muslim in India are a creation of the British, who enforced uniformity on the vast and diffuse array of devotional Indic practices.

Despite the exuberances of the anniversary this year, the Magna Carta is more symbolic than substantive. This was also the case during the colonial period, both in the metropole and in the colonies. And until the UK is able to face its colonial past the Magna Carta will continue to be weaponised as a symbol of ‘British liberty’ by reactionary UK politicians.

Ian Sanjay Patel is a writer and academic. He has a PhD from Cambridge University and has held academic posts at the University of East London and King’s College London. His writing has appeared in Al Jazeera, The Guardian, and the New Statesman among other publications.