Peter Nias (University of Bradford)

Diaries are full of them. So are the television and radio. Books, newspapers and magazines revel in them. Events are timed to coincide with them. Funding bids excel in digging them up. Web sites offer up seemingly endless hits from which to choose.

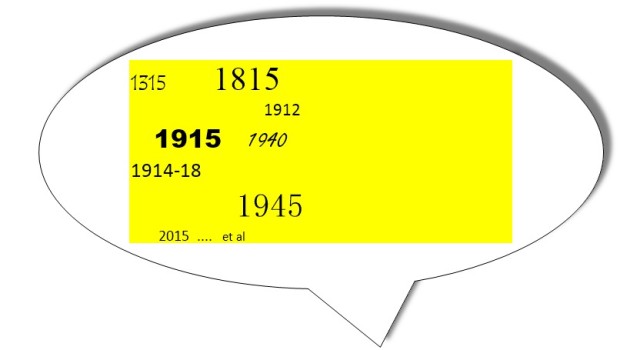

This month we have the octocentenary of the Magna Carta and the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo. This year we have the sexcentenary of the battle of Agincourt. There is the centenary of the Women’s Institute, the centenary of World War One and the purchase of Stonehenge for £6,600. There is the 75th anniversary of the Blitz – World War Two city bombings. Also the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, of the ending of World War Two and of the first re-delivery of bananas to Britain.

Welcome to the remembrance garden of public anniversaries, and it’s not only war history either.

Are they interesting? – yes. Educational? –when put in context. A thinly disguised narcissistic patriotism? – yes. Too much about violence (or are they really about victory?) – yes. A perverted use of the word ‘celebration’? – it seems so. A modernist montage of the past which constrains thinking about the future? – hmm, quite possibly.

How did we arrive at this anniversary mania? Such events have always been observed, of course, but they have proliferated and intensified over the last couple of decades. The associated term ‘heritage’ has emerged from obscurity to become a sacrosanct co-conspirator. What started out many years ago as a celebration of the ‘good old days’ (and bad ones too) has grown to become a growth market, a lucrative and apparently necessary attachment to daily life. Was it the anticipated ending of the millennium that gave the impetus? Whatever the cause, the net result is that we are driving uncertainly along the future road whilst gazing at the anniversaries in the rear view mirror.

The rapid pace of change throughout the 20th century and into the 21st has meant that we seem to prefer to reflect on events in the past rather than to look forward. These experiences may be positive or negative, but at least they are safely encompassed in history. The interlude allows ‘old father time’ to exercise his soothing touch.

Anniversaries as personal and public memory give structure and stability to societies, and rightly so. They allow happy or sombre reflections on what has occurred, and enable people to move forward. However, whilst such memory and memorials are good things, the excessive exploitation of the words ‘anniversary celebration’ is quite another. It has become too close to ‘celebrity’ and ‘partying’, despite half-hearted attempts to downplay the normally joyous interpretation of ‘celebration’ to really mean a more sombre ‘cautious remembrance’.

So why have we, especially in the most recent generation, become so intensely keen on such remembering? A few thoughts. First, some decennial considerations.

In the 1950’s and 60’s, and perhaps into the 70’s, the past living memory was not good. Those who lived through two world wars and the depression might have wished they could have skipped those times. Instead, they concentrated on looking to their children – the post-war baby boomers – to make a better job of the future. In the later 1970’s and into the 80’s the people who were brought up in the ‘never had it so good’ era started to have the time, money and inclination to look back. Even so, it was selective viewing, arguably preferring to remember the distant 19th century ‘poor law’ living rather than the awful 20th century. By the 1990’s and then into the 2000’s the wish to look into the past really began to take off. We were almost wallowing in it, wanting to look back up to one hundred years and one thousand years. Now in the 2010’s, anniversaries are still going strong in the popular mind, aided and abetted by heritage lottery funding.

Second, nostalgia may be a feeling that increases with age. There are now more older people about. There are currently significant numbers of the aforementioned post-World War Two baby-boomers aged 60+ in the population, many with good levels of education, affluence and time, and who are also avid voters. These attributes combine into an economic and political demand for the past. Whether this is expressed in, for example, visits to outdoor museums, to watching and perhaps following in the railtracks of Michael Portillo at home and abroad, or to delving into local and family history, or seeking funding for heritage projects, it adds up to be a well-financed and supported industry.

Third, ‘anniversary’ may be seen as a paradoxical rationalisation of catastrophes. Recent and current centenaries hold some clues. Scott’s Antarctic expedition and the Titanic were human and technological tragedies which have been transformed into ‘glorious failures’, reflecting a time when British people still strived to master the world. Now we hear about the political-and-everything-else tragedy of the First World War with its ‘glorious dead’ and the gradual loss of empire. Remembering the times ‘when Britain was great’ tries to bolster a now somewhat deflated ego. Such societal reflections are a kind of post-dated justification of past jingoistic endeavours. But are they also escapism to avoid knuckling down to the present and for what is to come? (climate change anyone?).

Fourthly, anniversaries thankfully place events in the distant past, their celebration being a kind of relief that most of us were not there at the time and that we do not want to go back.

A latter-day angle is that anniversaries have become agreeable excuses for festivities to accompany whatever occasion is being highlighted, the millennium being one example. A good idea of course, but it sounds as though these ‘jollies’ are increasingly being held in the restaurant at the end of the universe. Namely, we continue partying until we cannot turn the clock back anymore.

The peace writer, Elise Boulding, introduced a concept of the 200-year present, arguing that things that happened up to a century ago still affect us today, and things that are happening now will affect us for up to a century in the future. Her message was that it takes a long time to get over wars, and other events, because they are so deeply engrained on the collective memory. It is imperative to move on, she implies, but all the time we are dragging ourselves back into the past.

Technological development has a part to play in this. Arguably we would not be remembering World War One quite so much if moving pictures had not been available at that time. Indeed, that we didn’t ‘celebrate’ the centenary of the Boer War was probably not only because it was a defeat (and it would raise the concentration camp issue, too) but also because there is no film available. It seems that the more film there is, the more is shown and the more the anniversaries can be illustrated and remembered. It’s easy copy to reel out the past.

There are certainly positive sides to anniversary commemoration. Remembering genocides are vital. Recalling events also helps when otherwise forgotten people, or politically ‘inconvenient’ actions, become more widely known and remembered. These have resulted in some acknowledgement of past wrongs and have inspired future positive deeds. The women’s movement has particularly benefitted, I would say, from the revelations of many previously unknown women.

But these constructive reminders of the past are being overtaken by the incessant re-living of the destructive. So when will a dose of reality kick in? And can all this help us address our still evolving post-modernist place in the world? Instead, what about toning down the ‘hello to all that’ and swap it with a Gravesian ‘goodbye to all that’?

We need to build on our past societal foundations, of course, but repeatedly showing films of their construction to remind us of them means that we don’t look up and around as much as we should.

So what could we do?

We could adapt a Cleesian adage: what have anniversaries done for us? Nothing! The Poet Laureate could create regular ‘anni-verses’ to explore why we desire to delve so deeply into past depths. For every celebrated anniversary we could have a public discussion on what we as a society may be doing on that subject in the same number of years ahead as that anniversary is in the past. We could review how other countries deal with their anniversaries, particularly those with a large young population who primarily look to the future rather than the past. Another way could be to omit one or other of the 70th or 75th anniversaries. Do we really need for public events to be held on both of these dates? Also, for multi-year military anniversaries why not concentrate all the war events of each year in one chosen week only? That can be put into practice for when the all-too-soon centenary of World War Two comes along.

Peter Nias is an Honorary Visiting Research Fellow in Peace Studies at The University of Bradford. He was formerly at The Peace Museum, Bradford. He writes in a personal capacity.