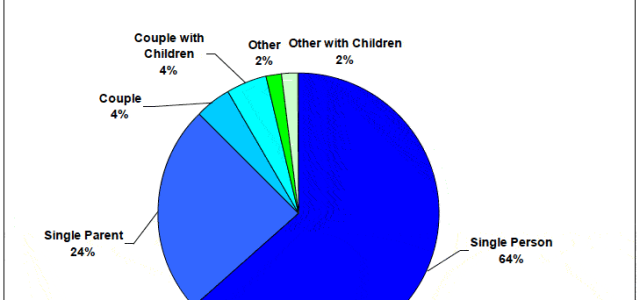

Figure. Scotland: Types of Household applying for Homelessness Assistance, April – September 2011

Isobel Anderson, University of Stirling

In November 2012, the Scottish Housing Minister confirmed that the commitment ‘to ensure all people facing homelessness through no fault of their own would have a right to settled accommodation’ would be fully in place by 31 December. Although not an unconditional ‘right to housing’, Scotland’s strengthened legal framework to protect people from homelessness received a human rights award (2003) and a UN recommendation for adoption across the UK (2009). More than a year on – to what extent are expectations still being met?

Homelessness statistics published in July 2013 gave the first detailed picture of outcomes as Scotland passed the 31 December 2012 milestone for abolition of the longstanding distinction between priority and non-priority need in Scotland’s homelessness legislation. Over the ten year implementation period, the proportion of homelessness acceptances assessed as being in priority need rose from 73% in 2001-2 to 96 % in 2012-13 and single people (26-65 years) had become the largest priority group, rather than an excluded group. At 31 December 2012, the target was fully met in 26 out of 32 local authorities, with two others achieving 98 and 99 % of the target and just four in the range from 88-97% of the goal. As of 1st January 2013 it effectively became a breach of the law to distinguish between priority and non-priority need in homelessness assessments, and Scottish Government statistics reported that from January to March 2013, all Scottish local authorities met this commitment.

The proportion of homeless households moving into settled accommodation as the final outcome of their application increased from 41% to 72% over the ten years, but the number of households in temporary accommodation virtually tripled between 2001-2012. A critical gap in the national data set, is that it does not indicate the period of time homeless households spend in temporary accommodation until settled housing is provided, but qualitative data from local authorities indicated lengthy periods in temporary accommodation became increasingly common.

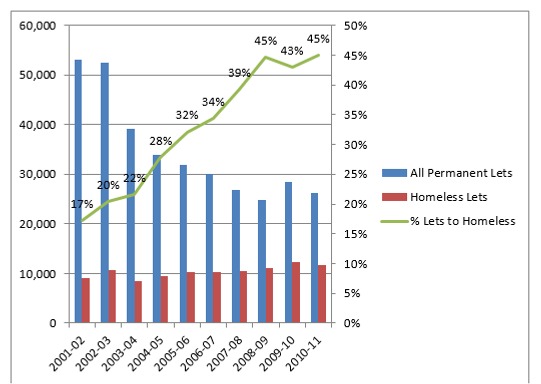

At least part of the driver towards a shift to homelessness prevention was the perceived high level of social allocations to homeless households during the implementation period. However, Figure 1 indicates that during 2001-2 to 2010-11, the absolute number of vacancies let by local authorities declined significantly. This meant that the relatively modest absolute increase in lettings to homeless households resulted in a disproportionately high share of the (declining) pool of total vacancies being allocated to homeless households. Even allowing for stock transfer and the role of Registered Social Landlords (RSLs) in housing homeless households, the decline in vacancies at least partly explains why, the proportion of lets to homeless households increased from 17 % to 45%.

Figure 1 Local authority permanent lettings during 2001/2 to 2010/11 and lets to homeless households

Source: Scottish Government, Management of Local Authority Housing (2010-11), Lettings

The post-2009 shift towards homelessness prevention and housing options assessments, combined with greater emphasis on settled accommodation in the private rented sector mean that proposals to increase landlord flexibility on allocations raise some questions for the sustainability of the modernised legal framework. Despite the perceived success of homelessness prevention in England, we still lack clear evidence on the extent of increasingly restrictive interpretations of the homelessness legislation (redefining rather than resolving the problem) and there remains a lack of clarity on the impact of homelessness prevention across the UK.

The Scottish policy landscape was bound to change over the ten year implementation period, but the shift towards a housing options approach, coupled with housing benefit reform appeared to overwhelm the final phase up to 2012-13 to an extent that the different effects could not readily be disentangled. In particular, there remains a need to better capture the lived experiences of those facing homelessness and seeking housing advice in the emerging housing options services.

In terms of social justice, the expanded homelessness safety net removed longstanding discrimination between different groups of homeless households, thereby increasing equality in access to housing. Continued monitoring of the strengthened framework remains essential to demonstrating both the abolition of the priority need test and the provision of settled accommodation within a reasonable time period. The long-term impact of the right to settled accommodation unintentionally homeless households will depend on whether the Scottish housing policy community sustains this strengthened legal framework; or whether the risk of policy blurring becomes increasingly pronounced as homelessness assessment is blended with broader housing advice services.

The case for progressive measures which genuinely prevent the trauma of homelessness is irrefutable, but should not be at the expense of diluting Scotland’s broad definition of homelessness or of diverting those facing homelessness away from the strengthened legal safety net which has been such a focus of national and international acclaim. Perhaps most importantly, a good deal more empirical evidence of the actual lived experiences of those facing homelessness in Scotland is needed in order to ‘de-blur’ the picture and fully assess implementation of the right to settled accommodation for homeless people.

Isobel Anderson is Professor of Housing Studies and Director of Research the School of Applied Social Science at The University of Stiirling. Her research has focused on housing, inequality and social exclusion in the UK and international contexts. She founded the working group on Welfare Policy, Homelessness and Social Exclusion within the European Network for Housing Research, jointly co-ordinating the group from 2003-2013.