Kim Allen, Kirsty Finn, Nicola Ingram

As COVID-19 grips the world, the UK government have been labelled as slow to respond; their public messages delayed and confused. Moreover the UK has stood apart from its European neighbours, seemingly refusing to learn lessons from Italy and Spain, and prompting accusations that the UK government are prioritising ‘Brexit over breathing’. Despite vast geographical, topological and health care policy differences, similarities have curiously been drawn between the UK and the US rather than Europe with little mention of the East Asian countries which have been relatively successfully in dealing with the pandemic.

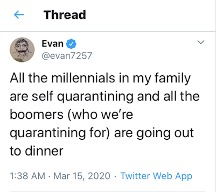

As the public grapples with the current crisis both traditional and social media have increasingly turned to discourses of generational difference and conflict to make sense of the varied reactions to the pandemic and the government’s guidance, pitting so-called ‘Millennials’ against ‘Boomers’ (the post WWII generation). We reflect on the generational tropes that have emerged in the last few weeks. Rather than reify these ‘hot takes’ or their characterisations of generations as truth, we consider what underlying concerns these generational framings express and what they obscure.

From Brexit to COVID-19: Generational framings and contemporary ‘crisis’

In the UK, notions of social division and polarisation have saturated the national debate since the 2016 Referendum to leave the EU. One of the most salient and oft-repeated of these is the idea of a generational divide between Leave-voting older generations and millennials who are commonly labelled ‘Generation Remain’. Born between 1981 and 1996, the label of ‘the millennial’ has become shorthand for a generational cohort are who are not only deemed ‘hardest hit’ by the Brexit process, but also one that is apparently unified by shared values and orientations towards cosmopolitanism, social-liberalism, and modes of governance that connect the UK globally.

Emerging in relational contradistinction to their older ‘Baby Boomer’ (or ‘Boomer’) counterparts, millennials dominate news headlines about everything from housing and education to climate change and mental health. They do so in a myriad of complex and contradictory ways: sometimes as a ‘lost’ generation, unfairly punished by austerity and falling wages, and ‘burnt out’ by precarious work; other times as fragile, work-shy and avocado-chumping ‘snowflakes’ whose ‘woke-ness’ is a threat to free speech.

As sociologists of youth (and as millennials/Gen-Xers ourselves) we have been struck by the many articles, tweets and memes filling our social media timeline over the last few weeks in which these generational tropes have been reanimated. We have participated in sharing these – sometimes for light relief; sometimes to express frustration when navigating our own family relations and responsibilities for elderly parents; more often because they have engaged our sociological imagination.

Indeed, whilst seemingly trivial and ephemeral, memes are an increasingly prevalent part of our digital lives and a communicative practice in which political and social issues and identities are expressed, debated and sometimes resisted. Those created and shared around COVID-19 provide insights into the ways in which contemporary concerns around citizenship and governance are being expressed through a distinctly generational lens. Focussing mainly on the ways in which different generational cohorts are perceived to engage to a greater or lesser extent in self-policing and ‘social distancing’, these are emblematic of the different ways generations are understood to perceive freedom, governance, and ‘expert’ knowledge.

For example, The Simpsons meme below is illustrative of wider cultural discourses which posit a distinctly generational response to COVID-19. In this case, Boomers are presented as in denial of the gravity of the crisis and its risks, unwilling to curtail their freedom for the greater social good, and sceptical of official knowledge. Contrastingly, Millennials – encapsulated by Lisa Simpson – emerge as hyper-responsible, socially-conscious actors who see COVID-19 as a social justice issue that has exposed the vulnerabilities of neoliberalism and extractive capitalism, and are engaging in emergent forms of collective action and mutual aid.

Covid Contradictions: Millennials as reckless or responsible?

Closer inspection of the way in which the figure of the millennial has emerged in the public and media discussion around the pandemic illustrates how the discourses relating to this generation are fraught with tension and contradiction. Indeed, millennials as a definable cohort have been held up to intense cultural scrutiny, leading to both praise and castigation, sympathy and recrimination.

In some instances, millennials figure as selfish and reckless, posing a risk to others and too selfish to take proper precautions (“‘Generation Me’ must start thinking about others if we’re to stop the spread of coronavirus”, The Telegraph 3 March 2020). Even one of the World Health Organisation’s top advisors used their platform to criticise millennials for not taking the virus seriously, stating they are ‘terrified’ by millennials’ sense of ‘invulnerability’.

Yet elsewhere, millennials appear as hyper-responsible, taking the virus and its impact on society more seriously than their apparently cavalier Boomer elders. Myriad articles and memes abound in which millennials are seen to be practising strict social distancing (even in the absence of clear messaging from the UK government) whilst older generations are accused of engaging recklessly in ‘business as usual’.

Recent changes to legislation introduced by government to enforce social isolation have been viewed by some as an attack on hard-won personal liberty by millennials who seek to police behaviours through ‘draconian’ solutions. Echoing the culture war generational narratives of Brexit, as millennials align themselves with global responses this too is read through the lens of anti-nationalism and a lack of support for the UK’s own responses, shoring up generational chasms.

Many of the memes generated and shared on social media work on the basis of the twin discourses of fragility and infantalisation, which play a central role in framing the predicaments and problems of the millennial generation, and generating particular affective responses, namely disdain. However, the positioning of millennials as fighting the good fight against the coronavirus and taking responsibility for the older generations puts these tropes under significant pressure. The response to this, as the above meme depicting a comfortable sofa reveals, is to present the actions and capabilities of Millennials as trivial and superficial through comparisons with hardy and brave ‘war-time’ generations. In a scathing attack on ‘millennials and everyone else who has bought into “the cult of me”’ an article in the Telegraph implies that COVID-19 will be as lethal to a culture of ‘woke-ness’ as it will be for human societies.

Conclusion

A rich body of scholarship in the sociology and cultural studies of youth has shown that media attention to the conditions and behaviour of young people is heightened at times of social, cultural and political upheaval, as the young come to figure as ‘symptomatic of the health of the nation’ (Cohen 2003). Millennials have been at the receiving end of this attention in recent years and the COVID-19 crisis has thrown problematic generational discourses into sharp relief.

Johanna Wyn identifies how young people are positioned in the media through twin discourses of youth as ‘threat’ and youth ‘as a symbol of hope for the future of society’ (2005: 24) whose potential must be realised in order to secure the nation’s wellbeing. Over recent successive crises – the GFC, austerity, Brexit and now COVID – we have seen both of these discourses working through the figure of the millennial, albeit in ways that are complicated and in many ways distinct from previous abject figures of youth such as chavs, or mods and rockers.

The fallout of COVID-19 is yet to be known. As with previous crises, there will be clear winners and losers. However, we are mindful that the notion of generational conflict that is being animated within contemporary debates around the crisis works to obfuscate the deep running class, spatial, gender and race-based inequalities that cut across generations. Moreover, we are concerned that these debates mask the linked lives of societies and intergenerational connections of care and compassion that are greatly needed, and we hope will emerge, as this pandemic plays out.

References

Cohen, P. (2003), ‘Mods and Shockers: Youth Cultural Studies in Britain’, in A. Bennett, M. Cieslik and S. Miles (eds), Researching Youth, 29-54, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wyn, JG, (2005) ‘Youth in the media: Adult stereotypes of young people’, in Williams, A. and Thurlow, C. (eds). Talking Adolescence: Perspectives on Communication in the Teenage Years, New York: Peter Lang. pp. 32 – 34

Kim Allen is a University Academic Fellow in the School of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Leeds; Kirsty Finn is Senior Lecturer in Sociology of Education at the University of Glasgow and Nicola Ingram is Professor of sociology of education at Sheffield Hallam University. They have written collectively and individually on youth, educational inequalities, class, gender, and employment.

Image Credit: Merkushev Vasiliy / Shutterstock