Lotika Singha

A major concern for Western feminism related to contemporary outsourcing of domestic work is the refusal of householders to consider themselves as employers with responsibilities, when they directly hire the services of a domestic worker, such as providing holiday pay. Indeed, even the International Labour Organization’s recent recommendations to member states for formalisation of domestic work centre on the notion that the relationship is an employer–employee one. This certainly is the case as regards a live-in domestic worker who works in a single household. But live-out providers work in a range of positions: directly employed by one (or more) households, as an employee of a third-party (for example, a cleaning services agency), as an independent declared own-account worker or an undeclared worker.

Despite this variation, two points are taken for granted in policy research. First, these workers are all employees, either of the households where they work or of agencies that employ domestic workers. Secondly, the best way forward to ensure decent work conditions involves following established, male-stream, ‘good’ employer–employee relationship-based business practices.

Here I contest this received wisdom by drawing on the views of a group of White British women working as domestic cleaning service-providers in the North West, North East and Midlands regions of England. I interviewed these women as part of a research project that interrogated the relationship between Western feminism and waged domestic work. I went into the field expecting to meet many a ‘Mrs Mopp’ – women with little education and work opportunities, familial caring responsibilities, living in households dependent on benefits, doing cash-in-hand work. But most of the cleaning service-providers I met ‘out there’ were operating as small businesses (18 of 27 women), particularly those who had level 3 qualifications (for example, A-levels), and their work status and experiences surprised me in many ways.

My data collection included a questionnaire that I asked the service-providers to fill out regarding details of the households they cleaned, such as the size of the house and the work they did. I used the word ‘employer’ to refer to their service-users as is the convention in published research and ILO policy documents. So it was a key moment when early on in the research when two sprightly English women, who had recently opened a cleaning business, firmly told me they were not employees and nor were their clients’ their employers. From then on, I asked all respondents how they defined their employment relationship, and these data gave me much food for thought.

Many women stated clearly that they did not want to be employees. This is not a novel finding. In several older American studies of domestic work, the live-out multi-client cleaners working informally also preferred the vendor–customer relationship. Yet, the employee–employer relationship is overwhelmingly accepted as the frame of reference because researchers commonly see it as the most secure way to work, that is assurance of basic legal and social employment rights, such as an income that takes into account inflation, regular paid holidays, job security in times of illness, a clear job description and humane treatment of the worker.

Evelyn Glenn showed that pre-industrialist traditions of personalism and asymmetry persisted in contemporary paid domestic work, and because of this, she considered the actors as employers and employees (1). Mary Romero, who used a Marxist feminist framework with a point of departure that assumed a clear modern–feudal dichotomy, discounted Glenn’s justification (2). She asserted that the domestic employer–employee relationship was ‘an instance of [capitalist] class struggle … [women] employing private household workers and childcare workers share[d] the same self-interest as other employers’. Romero’s rationale appeared to be driven by her choice of analytical framework rather than her respondents’ experiences: who, as she showed, had been establishing ‘business-like’ working conditions using strategies of self-employment, such as negotiating fees and benefits individually with each ‘employer’.

More recently, Helma Lutz’s (3) comment following her attempt to justify why ‘employer’ and ‘employee’ are the right terms appeared to end in confusion. She based her argument on the premise that the work is ‘socially necessary “work”’ but ended up noting ‘the absence of a contract and the fact that the work is performed in the private sphere give rise to functional and terminological diffuseness’. Her respondents did not share this idea, as she notes they often rejected the ‘employee’ label. Yet the research team decided to overlook the workers’ view, because, as researchers, they ‘knew’ it obfuscated the power–dependence equation in domestic work.

Anecdotal evidence indicates that the self-employed status of other domestic service-providers such as plumbers and external window cleaners, is not contested. The UK’s employment status indicator confirmed my respondents’ claim of being self-employed. Thus, as a reflective feminist researcher, I could not easily label them ‘employees’ or base policy suggestions on this employment relationship because that is the dominant top-down view. Using this approach, I found my respondents’ experiences of domestic cleaning service provision raises issues regarding some of the conditions of formalisation of domestic work as are being proposed more generally.

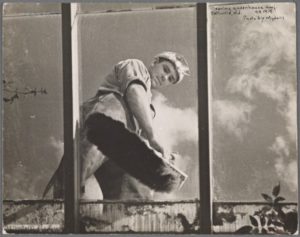

The service-providers found the contractual obligations of being employed constraining. Indeed, across cultures, research shows how capitalist cleaning agencies have co-opted the ‘wages for housework’ debate to give back to women – and men, as the image shows – their work under Taylorist conditions, reminiscent of historical servitude. Through both personalism and depersonalism, and cleaning to pre-prepared scripts, the work of cleaning is reduced to mindless labour, resulting in disenfranchisement and exploitation, as for other low-wage agency workers.

Bowman and Cole (4) argue the recently established Swedish cleaning companies offer a progressive model, protecting workers by clearly structuring the work: no picking up after people and no ‘potentially dangerous’ tasks such as ‘cleaning windows and moving furniture’. However, in the UK, window cleaning (from the inside) forms part of outsourced cleaning and none of my respondents objected to it. They valued their ability to decide which services to offer and which risks to take. Meeting prospective clients and decision-making – the negotiations where ‘power’ can be exercised – were part of what made the work more interesting and challenging than a job in a retail organisation or administrative office work. It made the women cleaning business-owners rather than just ‘the cleaner’.

All the registered service-providers I interviewed had professional indemnity insurance. Many had had Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) checks. But they did not do ‘written contracts’. Several respondents gave me thoughtful reasons why ‘fair’ contracts that are meant to safeguard workers’ rights are not always appropriate. For instance, older people, who may be frequently in and out of hospital are more comfortable with an agreement that takes their week-on-week status into account. The service-providers did not think it was reasonable that they should have to pay if they were suddenly taken ill and were not at home. They were willing to negotiate verbal agreements that recognised that service-users were not just clients but had wider lives that could impact on their outsourcing of domestic work. Also, they themselves were not atomised workers and each workplace was different. Their job was not just to hoover and spray a lot of room freshener for effect, but to leave each house feeling warm, welcoming and individual. Thus establishing rapport and, subsequently, a friendly work relationship based on mutual trust was important. Should feminists be dismissing these views as ‘astonishingly’ pre-modern, as described by Lutz?

The service-providers also preferred to reserve the right to drop customers and I argue that for good service-providers, this right can considerably raise their negotiating power as most service-users do not want to lose their ‘cleaning fairy’. In long-term relationships, terms of service can alter as household configurations change. Thus, these women were not behaving irresponsibly. Rather, they were participating in a considered appraisal of ‘good’ contemporary business practices that in real terms often provide only lip service to many workers. For instance, contracts that advise employers to provide their live-in workers with ‘adequate food’ without defining what this means still leave workers vulnerable to abuse. The Equality and Human Rights Commission’s research on commercial cleaning shows some UK cleaning agencies do not given copies of or even issue contracts to employees, whereas elsewhere, cleaners may not read contracts or understand the contents.

Although the service-providers accepted cheques and direct bank transfer, they preferred payments by cash per visit from the elderly clients with health problems whose cleaning needs may vary from week to week. Indeed, cash payment does not implicitly imply ‘informal’ work or that a service-provider ‘does not know their way around a self assessment tax form’. Some service-providers issued receipts, but reported that customers could appear ‘bemused’, which the service-providers found belittling.

As regards self-employment more generally, concerns have been raised recently about the validity of this form of work at the lower end. In particular since the 2008 recession, organisations have been co-opting the principles of self-employment to avoid fulfilling employed workers’ rights. Workforces are split into a small group of permanent employees and a larger group of floating workers who are coerced into presenting themselves as ‘self-employed’. Such workers are deemed doubly vulnerable. But at the other end, some middle-class men and women are downshifting in search of ‘meaningful’ work, having failed to find self-actualisation in elite careers. In the presence of sufficient education and financial capitals, ‘kaleidoscopic’ non-linear careers and mucking out on the farm after graduating from Harvard may even be lauded. Sociological analyses of these work experiences take a philosophical turn, drawing on concepts of selfhood and individualism: ‘these men and women have the access and “ability” to imagine and carry out – more meaningful – work-life trajectories’ (5).

Although my respondents’ work was stigmatised as ‘low-status’, they, like people in other work elsewhere, had made reflexive decisions about moving on within the constraints of their social locations. Jesse Potter’s observation that middle-class opt-outers’ attempts at ‘weav[ing] the disparate parts’ of lived lives ‘together to form some sort of a more coherent and meaningful whole’ should be ‘an integral part of this thing we call career’ also applies, as Potter himself conjectured, to people with ‘just’ a job. That is, my respondents’ precarity was not due to being self-employed per se, but to the structural factors that maintain age-old hierarchies in ‘egalitarian’ societies. For example, the continued reluctance of several Western states, including the UK, to accord full legal recognition to domestic work, and the artificial division of work into high and low status based on ‘skill’. A Canadian study by Wall of self-employed nurses showed that self-employment was integral to working practices that were fulfilling for both the nurses and their patients, and commensurate with the nurses’ values (6). Wall’s nuanced conclusion was that like gender, analyses of self-employment require an intersectional approach to understand where exactly the problems lie.

More generally, a single model of domestic work risks becoming deterministic and possibly difficult to realise in a world where traditional male white-collar jobs are being replaced by ‘flexible’ working spaces and schedules, individualised contracts, and neo-Taylorist working conditions, and where career-jobs are meandering along the ‘ghost of the stable path’ (quoting Potter). Also, freedom and autonomy appear increasingly one step ahead of the worker with the introduction of ‘innovative’ management processes such as ‘Lean’. Care work often suffers under job conditions that focus only on physical aspects of care. I propose feminist policy research focusing on improving domestic work conditions should explore further the employment relations different kinds of domestic workers themselves prefer, rather than starting from a position that assumes every low-paid worker is, or should be, an employee.

Notes:

(1) Glenn, E.N. (1992) ‘From servitude to service work: historical continuities in the racial division of paid reproductive labor’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 18(1), 1–43.

(2) Romero, M. (2002). M.A.I.D. in the USA. 10th Anniversary Edition. London: Routledge, pp 7–8.

(3) Lutz, H. (2011) The New Maids: Transnational Women and the Care Economy. Translated by Deborah Shannon. London: Zed Books, pp. 33,187.

(4) Bowman, J.R. and Cole, A.M. (2014) ‘Cleaning the ‘People’s Home’: the politics of the domestic service market in Sweden’, Gender, Work & Organization, 21(2), 187–201, at p. 191.

(5) Potter, J. (2015) Crisis at Work. Identity and the End of Career. Basingstoke, Hants: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 9; also (a) Mainiero, L.A. and Sullivan, S.E. (2005) ‘Kaleidoscope careers: an alternate explanation for the ‘opt-out’ revolution’, Academy of Management Executive, 19(1), 106–123; (b) 2005; Wilhoit, E.D. (2014) ‘Opting out (without kids): understanding non-mothers’ workplace exit in popular autobiographies’, Gender, Work & Organization, 21(3), 260–272.

(6) Wall, S. (2015) ‘Dimensions of precariousness in an emerging sector of self-employment: a study of self-employed nurses’, Gender, Work & Organization, 22, 221–236.

Lotika Singha is currently a PhD student in the Centre for Women’s Studies at the University of York. Her research explores the ‘problem with a name’ in feminism and paid domestic work, through the lens of outsourced domestic cleaning in the UK and India. She has previously worked for several years both as an employee, as a hospital orthodontist, and as a self-employed copy-editor and proof reader. The research presented here is supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ES/J500215/1].

Image credits: Forms of employment: Lotika Singha

Cleaning greenhouse roof. Prince Georges County, Beltsville, Maryland. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1935 Aug. Three men at dusting books: Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.