Trude Sundberg

A 62 year old woman is pulled out of the bus she is travelling on and beaten up. Why? Because she has dark skin and head scarf. In a different country, at a different time a disabled person is doing her shopping at her local supermarket with a friend, and when asking a question to the shop assistant, the shop assistant turns to her friend to answer the question. In another location, a recently unemployed man opens the newspaper and sighs, another day, another headline about lazy welfare claimants.

These three stories have something in common. They all relate to how our negative stereotypes of certain groups in society affect people’s daily lives, and reflect an overall lack of solidarity and concern for some groups in society.

This is particularly important to emphasize in the wake of the latest terrorist attacks in Paris, where governments again are faced with a choice, a choice of dividing or uniting. Should they choose to target certain groups, associating them with labels and stereotypes, and, as a result, divide societies further? Or, should they seek to use rhetoric that unites? Attitude research shows that media coverage and language, political rhetoric as well as policies associating certain groups with negative stereotypes can lead to divisions and negative stereotypes amongst the wider public. In other words, negative stereotypes used in the media, by politicians and in our daily lives have real consequences not only for individuals’ lives but also for the concern people in societies show for each other.

Divide and conquer – the dominance of negative stereotypes

Now, in what ways do media, political debates and policies influence negative stereotypes? In the examples above I point to very different groups who are all associated with negative stereotypes; immigrants, disabled and the unemployed. I could also have added other groups, such as single mothers or even LGBTQ+ individuals. The point being that negative stereotypes, defined as a set of negative traits associated with a group, enforce and reinforce differences between groups, in particular when they are repeated in the media, by politicians and reflected in policies.

One may ask why media and politicians choose to use these stereotypes, if they divide societies and create less concern for the living conditions of some groups in society. The motives may vary. For politicians, political parties can gain votes and popularity by distancing themselves, from groups that are seen to embody negative stereotypes. For the media, stereotypes can be used to appeal to an audience, and, on a more cynical note, to enable more sales. Thus, by dividing groups, they can conquer both readers and voters. An example of an area where we could tell a success story is immigration. Immigrants have been found to contribute positively to the economy. In contrast to these findings, the focus in the media and amongst politicians has been on immigrants as a burden to the economy.

In the media, examples would be the (in)famous ‘Benefit Street’ on TV, articles on benefit scroungers, stories on radicalized young men, and immigrants as benefit tourists. Stereotypes are also present in political rhetoric when politicians refer to scroungers and skivers, or emphasizing certain groups as potential dangers to society.

Stereotypes are also strengthened and reinforced by policies created by politicians and policymakers. An example is that welfare policies related to disability policies and those out of work. In the UK, these now contain stricter criteria that recipients have to fulfil to be deemed ‘deserving’. These criteria mean showing that they are not ‘lazy’, an often mentioned characteristic of the unemployed, by, for example, demonstrating that they submit a certain number of job applications each week. All of these are examples of how negative stereotypes are not only existent amongst the public, but also prevalent in the media, amongst politicians and in policies.

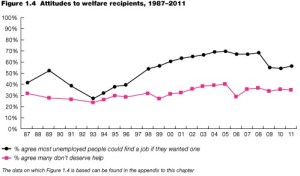

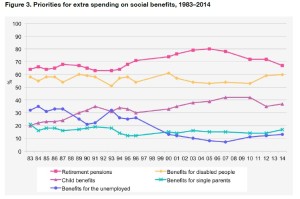

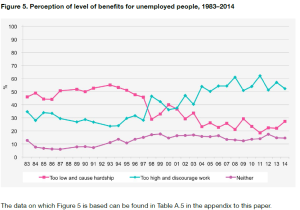

Amongst the wider UK population we have seen a harshening of attitudes towards those receiving benefits in the UK, more negative attitudes towards some groups that are deemed as lazy, e.g. the unemployed, as well as suspicions in terms of the consequences of receiving benefits (see below for findings from the British Social Attitude survey). This means that there seems to be a rising belief in the welfare dependency rhetoric, e.g. receiving benefits makes you lazy and unwilling to work.

Why does this matter?

In attitude research, and in particular when focusing on attitudes, perceptions and stereotypes towards certain groups in society, we often find that larger inequalities and distances between different groups increase tendencies of judging groups harsher, of associating them with negative stereotypes and having lower levels of concern for their living conditions. Importantly, feeling that a group is similar to yours is associated with more positive attitudes towards it. The area of attitudes towards immigrants has several examples of this, and we find that attitudes towards immigrants are more negative in places where there are fewer immigrants.

Negative coverage in the media and negative language reinforces negative stereotypes, further strengthening and reinforcing pre-existing perceptions. As a result, coverage in the media, political rhetoric and policies become important, because they influence stereotypes, and have very real consequences on the lives of those associated with them, as well as the level concern we have for the wellbeing of these groups. In this context, awareness and reflexivity is called for. Journalists, politicians and policymakers need to take into account the danger of dividing societies – rather than uniting them in difference – when they write about, talk about and make policies. A negative focus in news stories, hostile political rhetoric and policies can distance welfare recipients from the majority, making them subject to further testing of ‘deservingness’. This then leads to further divisions in society and harshening of attitudes.

Negative stereotypes also have a further implication, beyond the lived experiences of being associated with a stereotype or dividing groups in society. What I am referring to is a real political impact through voting. Stereotyping, perceptions and attitudes can influence which parties citizens vote for, which means that negative judgements can be further reinforced through parties not only shaping their manifestos to attract voters, but through these policies being implemented. The result being a vicious circle reinforcing negative stereotyping, causing deeper divides in society, and lower concern of a majority for the wellbeing of minority groups.

What to do?

We need a greater emphasis on the complexities and fragilities minority groups in societies face. The experiences of stigma, discrimination and negative stereotypes should be reported on. The language in the media should reflect these aspects. Politicians and policies need to use language that unites, and policies that builds solidarity across groups.

Politicians´ failure to understand long term consequences in society of a divide and conquer type politics is a problem that is more likely to bring about more violence, more difference, and deeper divides. The importance of reflection and contemplation, rather than gut reactions based on negative stereotypes is needed. It is needed if we seek to create societies based on solidarity amongst citizens, rather than further division.

Research has consistently shown that for a more stable society to be created, with citizens who have higher levels of concern for each other, more contact between and across groups, not less, is needed. This should ideally be combined with more socio-economic equality, as we find higher levels of solidarity and interpersonal trust between citizens in more equal societies. More conditionality and requirements of welfare recipients to prove their ‘deservingness’ or disassociate themselves from stereotypes of being lazy through different activities divides rather than unites the population.

Overall then, this is a call to seek language and policies that unite, rather than divide to build a society where citizens have higher levels of concern for each other’s wellbeing.

Trude Sundberg is Lecturer in Social Policy at the University of Kent’s School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research and one of two Co-directors of the University’s Q-Step Centre, a Centre awarded 1.15 million pound to help create a step-change in quantitative skills amongst our social science students as well as the wider population in Kent, and in particular students in Secondary Education. Her main research interests are welfare legitimacy and the values, attitudes and perception underlying and supporting different types of welfare arrangements across the world.

Image: From the Qatar Culture Club Blog