Jessica Paddock and Alan Warde

The challenges associated with mitigating climate change make us ever more aware of the need for urgent action. Last year, the Governor of the Bank of England warned the insurance market at Lloyd’s of London that “the challenges currently posed by climate change pale in significance compared with what might come”. Mark Carney added, “the far-sighted amongst you are anticipating broader global impacts on property, migration and political stability, as well as food and water security. So why isn’t more being done to address it?”. This question echoes the messages of academic research, social movements, voluntary sector and policy campaigns aimed at changing our behaviour. So how might we overcome our stubborn reluctance to change our consumption habits in order to meet reductions in CO2 emissions?

Most people find changing their everyday routines difficult. If pain is anticipated obstacles are commensurately greater. Hence, much well-meaning policy aimed at reforming consumption is often unpopular. Many of the targets for behaviour change interventions and green campaigns are things we enjoy the most and that make our lives that little bit easier; such as foreign holidays, eating the foods we prefer and have become accustomed to, and driving pretty much everywhere. We need only recall the outcry that initially met the replacement of the incandescent light bulb, as well as the more recent move to reduce plastic bag usage, to imagine reactions to plans for the extreme reductions in fossil fuel consumption required for less energy intensive ways of living. Hopes that scientific and technological developments will bring enough new solutions to the market in time to obviate the need for change will, almost certainly, prove optimistic. Nor can we expect many to shun a life of employment and consumerism to pursue an alternative, simple, green way of life. As argued elsewhere in this issue of Discover Society, we might do better to consider how the reconfiguration of socio-technical systems and daily life practices might bring about the scale of social shift needed, and especially shifts which might seem pleasing rather than punitive.

Where better to start this imagining than around a practice that we each engage in every day and which demands much in the way of precious resources: eating. Systems of distribution for consumer retail, display, and consumer travel to provision the home with ingredients, which are then prepared and cooked in individual kitchens, comprise a complex of energy intensive practices that could be reconfigured for sustainability. Policy interventions might be targeted less at what people eat, more at where and how food is consumed.

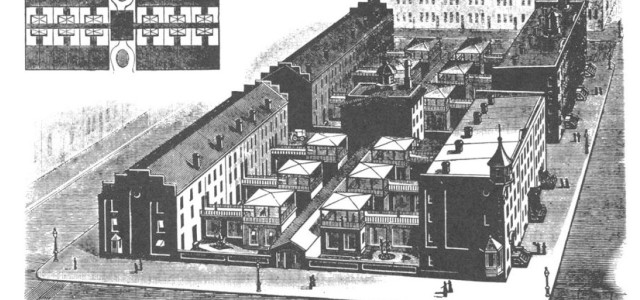

In the early 1900s, with women’s liberation from the drudgery of domestic labour in mind, Marie Stevens Howland and Alice Constance Austin proposed the reconfiguration of household design, most notably eliminating kitchens! Emphasising economy of space, labour and material resources, Dolores Hayden (1978) described Austin’s designs thus:

“each kitchenless house was connected to a central kitchen through a complex underground network of tunnels, where all telephone cables, water electric and gas cables were also housed. Railway cars would bring cooked food and laundry from the centre of the city to a neighbourhood hub, from which small electric cars would deliver to each home. With public delivery systems handling all shopping, residents have access to the city centre on foot, creating a more restful city.”

This utopian vision did not come to fruition, not, one suspects, because women refused to abandon heavy domestic labour but rather because a supporting infrastructure was neither available nor apparently feasible in the immediate future. Now is a good moment to revisit aspects of their proposals in the light of issues of environmental sustainability (see Spurling et al., 2013). Could Britons fare well if more people were persuaded to eat more of their main meals outside of the home? Trends in eating out and results from our recent survey suggest that people might see this not as a sacrifice, but rather as a welcome prospect.

Food prepared and eaten away from home plays an increasing role in the nation’s diet. The most recent wave of the Food Standards Agency’s ‘Food and You’ Survey found that 75% of respondents reported eating out or buying food to take away in the last week, and 10% reported eating out six times or more in the last week. To understand more about patterns of eating out, change over time, and its bearing on the potential to reconfigure ways of provisioning, cooking and eating to be more sustainable in the future, we have revisited a 1995 study of eating out in Britain (Warde and Martens, 2000). Comparing these two sets of survey data reveals not only that eating out is still on the rise, 20% of the sample eats a main meal out once a week or more, but is also enormously enjoyable. 97% report having enjoyed the last main meal out, and not because it was a special occasion: 20% of the last main meals out were special occasions, with 75% described as a ‘convenience or quick meal’ or ‘just a social occasion.’ 61% disagreed with a statement ‘I prefer the comfort of my own home to a meal taken outside the home’. Eating out is clearly appealing.

Of course, while Britons overall may not want to let go of meals prepared and eaten at home altogether; women in particular might be ready and willing to forego them more often. While men and women eat out equally frequently, 60% of women agree strongly that they ‘would like to eat out more often’ compared with 40% of men. Twice as many women as men in 1995 agreed strongly that they liked to eat out in order not to have to prepare a meal themselves, a proportion unchanged by 2015. 61 per cent of respondents overall agree that they like eating out as it gets them out of the house, with 65 per cent of those agreeing strongly with this statement being women. Escaping tasks like cooking and clearing up, which women still perform disproportionately, underpins their desire to eat out more often.

On the other hand, we might imagine further objections and constraints upon increased eating out. For a start, people also say that they like cooking and entertaining at home. 69% agree that they have an interest in everyday cooking, and 71% are interested in cooking for special occasions. Numerous mass media programmes on cooking encourage such a response, although the actual time spent on cooking in Europe and North America has fallen steeply in the last forty years. Thus, although eating out was enjoyed as a treat in the past, we might imagine a future where this is reversed; where turning on your oven to cook a meal for a small number of close friends or family becomes the special thing to do. If currently routine cooking is believed to be a key means to show affection and to care for a family surely an alternative can be imagined. An additional key challenge would be for the catering industry and restaurant sector to devise means of providing affordable meals that fit with household budgets of all shapes and sizes. Interestingly, the meals most often described as having been eaten out in 1995 and 2015 remain remarkably similar; roasted meat or fish with a staple carbohydrate and vegetables (see also Warde and Yates, 2015). Presently only 9% agree that eating out is poor value for money, and while more regular eating out would stretch budgets in different ways an expanded industry should be able to meet demands for nutritious and tasty meals that conform to popular ideas of a good dinner at the right price.

So while abandoning our kitchens may at first sound unconscionable, it may be more attractive than many other options, in relation to the radical changes needed to deal with climate change. Supporting an infrastructure for more eating out and less cooking at home might achieve substantial reductions in energy and resource consumption. We do not know for sure, as this question is never asked. More research is needed to understand the shape, size and trade-off involved in moving from one mode of eating to another. For now, we can only imagine what might be possible. For example, commercial motives for efficiency in small businesses might conserve resources and prevent waste. More eating out and more use of prepared meals delivered to homes may reduce the energy consumed at home in cooking and storing food, but also reduce environmental burdens associated with a system of provision which requires retailers to move goods and produce through supermarkets which require dispersed populations to drive a private car to collect raw ingredients, which then require further energy-intensive treatment. Maybe the time for the kitchenless home has come! Or, at least, if, given a supporting commercial context and material infrastructure, cooking at home became the exception rather than the rule, then a utopian vision could get closer to realisation. We might even enjoy ourselves more at the same time.

Further Reading

Hayden, D. (1978) ‘Two Utopian Feminists and Their Campaigns for Kitchenless Houses’, Signs, Vol.4 No.2, pp. 274-290.

Spurling, N., McMeekin, A., Shove, E., Southerton, D., & Welch, D., (2013) ‘Interventions in practice: re-framing policy approaches to consumer behaviour’, SPRG Report, Sept

Yates, L. and Warde, A (2014) ‘The Evolving Content of Meals in Great Britain: results of a survey in 2012 in comparison with the 1950s’, Appetite: Vol 84: 299-308.

Warde, A and Martens, L. (2000) Eating Out: Social Differentiation, Consumption and Pleasure, Cambridge University Press.

Alan Warde is Professor of Sociology and Professorial Research Fellow at the Sustainable Consumption Institute at the University of Manchester. Between 2010-2012, he was the Jane and Aatos Erkko Visiting Research Professorship for Studies in Contemporary Society, at the University of Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, Finland. With Tony Bennett, Mike Savage, Elisabeth Silva, Modesto Gayo-Cal, and David Wright, he is author of Culture, Class, Distinction (Routledge, 2009) and The Practice of Eating (Polity 2016), editor of Consumption (4 volumes, Benchmarks in Culture and Society: Sage, 2010). Jessica Paddock is a Research Associate at the Sustainable Consumption Institute , University of Manchester, and is currently working on revisiting the study ‘Eating Out in Britain: Social Differentiation, Consumption and Pleasure‘ with Alan Warde. She has a PhD in Sociology from Cardiff University, and her main research interests are concerned with class culture, gender, food consumption and environmental change. Recent publications include ‘Household Consumption and Environmental Change: Rethinking the Policy Problem through Narratives of Food Practice’, Journal of Consumer Culture; ‘Positioning Food Cultures: Alternative Food as Distinctive Consumer Practice’, Sociology; ‘Invoking Simplicity: ‘Alternative’ Food and the Reinvention of Distinction’, Sociologia Ruralis (2015 Vol 55 (1) pp.22-40); and Baker, S. Paddock, J., Smith,A., Unsworth, R., Hertler, H. and Cullen-Unsworth, C. (2015) ‘An Ecosystems Perspective for Food Security in the Caribbean: Seagrass Meadows in the Turks and Caicos Islands’, Ecosystem Services.