Irene Zempi (Nottingham Trent University) and Imran Awan (Birmingham City University)

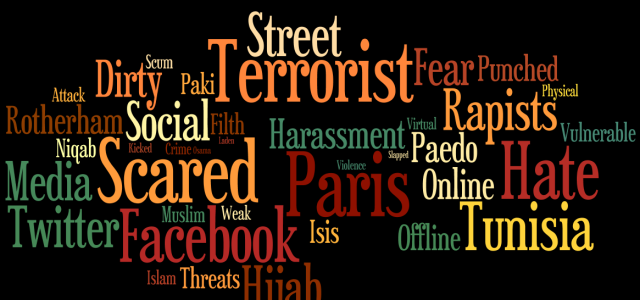

Following the terrorist attacks in Paris and Tunisia in 2015, and in Woolwich, south-east London where British Army soldier Drummer Lee Rigby was murdered in 2013, there has seen a sharp rise in anti-Muslim attacks. These incidents have occurred offline where mosques have been targeted, Muslim women have had their hijab (headscarf) or niqab (face veil) pulled off, Muslim men have been attacked, and racist graffiti has been scrawled against Muslim graves and properties. Moreover, there has been a spike in online anti-Muslim attacks where Muslims have been targeted by campaigns of cyber bullying, cyber harassment, cyber incitement and threats of offline violence.

Against this background, we were commissioned and funded by the Measuring Anti-Muslim Attacks (Tell MAMA) Project, to examine online and offline experiences of anti-Muslim hate crime in the UK. Specifically, the aim of our project was threefold: (a) examine the nature and extent of online and offline anti-Muslim hate crime directed towards Muslims in the UK; (b) understand the impact of these attacks upon victims, their families and wider communities; (c) offer recommendations on preventing and responding to anti-Muslim hostility, both online and offline.

With this in mind, we conducted 20 interviews with Muslim men and women who have been victims of online and offline anti-Muslim hate crime, and had reported these experiences to Tell MAMA. A common characteristic amongst our participants was that they were ‘visibly identifiable’ as Muslim. For example, some of the female participants wore the jilbab (long robe for Muslim women), hijab (headscarf) and/or niqab (face veil), and some of the male participants had a beard and/or wore a jubba (long robe for Muslim men) and a cap that identified them as Muslim.

Our participants reported a range of anti-Muslim hate experiences from abuse they suffered online (on social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, myspace, hi5 and bebo) where they were threatened with violence to offline abuse where they suffered verbal and physical abuse on the street. In the online world, participants’ experiences included hostile comments, racist posts, fake id profiles, messages and images used to harass and incite violence against them. For example, in one case a female participant had an image of her redistributed on Twitter with the caption ‘You Burqa wearing slut’ and in another case the perpetrators found the address of the victim and threatened her with violence. Typically, participants were identified as ‘Muslim’ by the perpetrators because of their online appearance, name or nature of comments that revealed their Muslim identity.

For perpetrators, the internet allows them to take on a new and anonymous identity, and to bypass traditional editorial controls, to share their views with millions. Online anti-Muslim hate messages can be sent anonymously or by using a false identity, making it difficult to identify the offender. The anonymity aspect in cases of online anti-Muslim hate messages is extremely frightening as the perpetrator could be anyone and the online threats can escalate into the physical space.

Similarly to the virtual world – where actual and potential victims are identified through the visibility of their Muslim identity by virtue of their appearance, name, or the topic of their posts – Muslims are equally vulnerable to intimidation, violence and abuse on the street, particularly when their Muslim identity is visible offline. Indeed, the research literature shows that ‘visible’ Muslims – such as Muslim men with a beard and Muslim women who wear jilbab, hijab or niqab – are at heightened risk of anti-Muslim hostility in public by virtue of their visible ‘Muslimness’. Specifically, popular perceptions that veiled Muslim women are passive, oppressed and powerless increase their chance of assault, thereby marking them as an ‘easy’ and ‘soft’ target to attack.

In addition to suffering online abuse, participants reported incidents of offline attacks including women being punched, kicked and having their hijabs or niqabs pulled off. In one case, a female participant was threatened by someone on the street who wanted ‘to blow her face off’. Additionally, we heard disturbing accounts of how Muslim men had also suffered anti-Muslim hostility in the workplace. In one case, a participant described how his work colleagues had purposively locked the room where he was praying. Typically, male participants felt too scared to report it to the police in case people perceived them as being ‘weak’ whilst female participants felt that the police would not take it seriously.

Moreover, we found that the prevalence and severity of online and offline anti-Muslim hate crimes are influenced by ‘trigger’ events of local, national and international significance. Terrorist attacks carried out by individuals who identify themselves as being Muslim or acting in the name of Islam – such as the Woolwich attack, the atrocities committed by ISIS and attacks around the world such as Sydney, the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris, and attacks in Copenhagen and Tunisia – induced a significant increase in participants’ online and offline anti-Muslim hate crime experiences. Additionally, national scandals such as the grooming of young girls in Rotherham by groups of Pakistani men, and the alleged ‘Trojan Horse’ scandal in Birmingham framed as a ‘jihadist plot’ to take over schools, were also highlighted by participants as ‘trigger’ events, which increased their vulnerability to anti-Muslim hostility, both online and offline.

Throughout the ‘fieldwork’ i.e. while doing the interviews we realised that both offline and online anti-Muslim hate crimes and incidents can have damaging impacts for victims, whose level of self-esteem and confidence are affected, as well as them living in a constant state of fear and anxiety. In this regard, many participants highlighted the relationship between online and offline anti-Muslim hate crime, and described living in fear because of the possibility of online threats materialising in the ‘real world’. The actual and perceived threat of anti-Muslim hate crime had forced them to adopt a siege mentality and keep a low profile in order to reduce the potential for future attacks. Many participants reported taking steps to become less ‘visible’ such as taking the jilbab, hijab and/or niqab off for women and shaving their beards for men in order to reduce the risk of future attacks.

Last but not least, we asked participants what they believed should be done to prevent anti-Muslim hate, both online and offline. They made a number of recommendations including encouraging fellow Muslims and wider Muslim communities to be confident in recognising, reporting and challenging such incidents; better media training in order to report stories about Muslims and Islam fairly without stereotyping them as ‘terrorists’, ‘extremists’ and ‘radicals’; the police taking steps to increase the confidence of victims taking forward; witnesses intervening (where possible and safe) to protect and assist victims of anti-Muslim hate, and inform the police; more information about anti-Muslim hate crime in the form of workshops, advertisements, posters, flyers, reports promoted in mosques, community centres, businesses, shops, cafes and schools; social media companies making their systems of reporting hate crime more user friendly; more diversity in the criminal justice system; challenging anti-Muslim rhetoric, and engaging schools in the debate. We hope that policy makers, the police, victim support, communities and other agencies and stakeholders concerned with anti-Muslim hate crime will use these recommendations as a means to create safer communities in Britain.

Irene Zempi is a lecturer in Criminology at Nottingham Trent University. Imran Awan is Deputy Director of the Centre for Applied Criminology at Birmingham City University. His new book Islamophobia in Cyberspace (2015) is published by Ashgate. For more information, please contact the authors or Tell MAMA for a copy of the report “We Fear for our Lives”: Offline and Online Experiences of Anti-Muslim Hostility.