Yvette Taylor and Emily Falconer (London South Bank University)

What and where are the spaces for queer religious youth? Who are in them? What sentiments and subjectivities are fostered in – and between – these spaces? Perhaps you are wondering if such spaces exist, and who might occupy them? You may have paused at the first question, noticing three seemingly clashing categories – ‘youth’, ‘religious’, ‘queer’ – that don’t normally sit side by side. You may imagine religion, sexuality and youth as ‘contradictory’, or be apprehensive that these spaces have come to be seen as sites of trouble and struggle, where widely held perceptions have often cast religion as automatically negative or harmful to the realisation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) identities.

A previous NatCen Social Research Report (#28: 2011-12) on British Social Attitudes implied a correlation between youth, secularisation and ‘liberal’ attitudes to non-heterosexuality. In addressing the meaning of a general decline in religion, the report suggests that the UK will continue to see an increase in ‘liberal’ attitudes to issues such as homosexuality and same-sex marriage. These apparent liberal attitudes to sexuality may, according to the report, ‘…see an increased reluctance, particularly among the younger age groups, for matters of faith to enter the social and public sphere at all’. And yet matters of faith continue to enter the public sphere…

From Wednesday 10 December 2014 couples are able to convert civil partnerships to marriage (if the partnership was registered in in England and Wales, or overseas in a consulate or armed forces base according to the laws of England and Wales), and again we hear widespread celebration and condemnation of this move from across the religious spectrum, queer communities, and general publics. Comments have invoked universal rights – and wrongs – and the ‘fit’ into family and future, as conveyed by Minister for Women and Equalities, Nicky Morgan, and Skills and Equalities Minister, Nick Boles: ‘Marriage is a universal institution which should be available to all. It is the bedrock of our society and the most powerful expression of commitment that two people can make. While civil partnerships remain an important part of the journey towards legal equality, it is entirely understandable why so many same-sex couples want to be able to enter into the institution of marriage and express their love in the same way as their peers’ (pink news).

It is interesting to consider how queer, religious, youth have come to be viewed as absent, awkward and contradictory, where public commentaries and social policies, including Equalities legislation, often address an older adult citizen (as consumer, employee, resident etc.). At disciplinary dis-orientations, the fields of ‘Youth Studies’, ‘Religion’ and ‘Sexuality’, are often separate, representing other bridges to cross and query. Some sociological studies into queer Christian identities have unpacked the experiences of those ‘wrestling the angel of contradiction’ (O’Brien in Taylor and Snowdon, 2014), noting too that Christian denominations can officially hold a variety of perspectives towards homosexuality, from wholesale acceptance, grudging ‘tolerance’ to condemnation. But often queer Christians are not officially welcomed or legitimised in the institutionalised church (as audiences, listeners, leaders – see Taylor and Snowdon, 2014).

In August 2014, The Independent published an article about the Christian rock star Vicky Beeching coming out. After moving through the painful story of Beeching’s ‘psychological torture, life-threatening illness and unimaginable loneliness, imposed all around from a supposedly Godly environment’, the article concluded that the telling of her story, and the happy ending of peace and resolution of sexual and religious identities, would be of huge comfort to other young queer Christians. The tone of the media coverage surrounding Beeching’s journey of resolution sits alongside other, even more playful and imaginative stories, of living with and through ‘contradictions’.

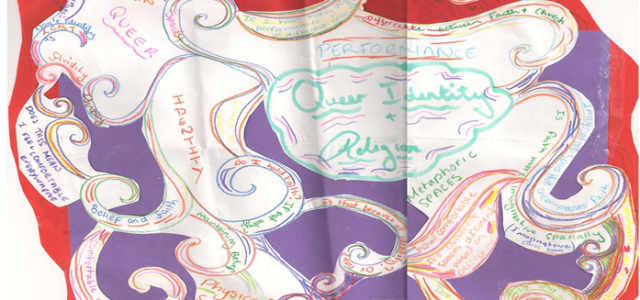

The project explored with interviewees the possibilities of queering religion. During fieldwork, interviewees were asked to keep a diary for a month to record everyday reflections, also completing ‘mind maps’, on the spaces, places and people they take up and talk to on a day-to-day basis (see the photo illustrating this article).

In thinking through religious-sexual meaning and movements, reflections and questions revolved around, the spaces where LGBTQ religious youth felt (un)comfortable: where to be ‘religious’ as a younger, queer person? Where to be ‘queer’ as a Christian? The circular, flowing representation is suggestive, perhaps, of the possibility of less binaried identities, and of hoped for and hopeful imagined spaces (‘metaphorical spaces’) of belonging, as well as material sticking points (‘physical spaces’).

Reflections were visually mapped onto a blank piece of paper with participants choosing different, creative, and colourful ways to express and display identity, movement and belonging. This exhibition reveals the creative ways in which ‘queer identifying religious youth’ express, relate and create their identities, illustrating negotiations, conflicts and celebrations. This has culminated in several exhibitions hosted by the Weeks Centre for Social and Policy Research (LSBU) including Making Space for Religion, Youth and sexuality? Implications for Policies, Politics and Public Imaginations. These exhibitions-as-impact, or impact-as-exhibition, have surpassed disciplinary and non-academic boundaries, involving young ‘religious queers’ themselves as experts in the field, queering secular and religious spaces through physically changing University and Church rooms.

Opening the panel discussion at St. George the Martyrs Church, across from London South Bank University, was Samuel, a young representative from Diverse Church. Samuel began with an apology he always gives on behalf of Diverse Church, which is to convey to anybody who is young, queer and religious how sorry he is if anybody has ever told them God doesn’t love them because they are LGBTQ. What followed was a powerful account of what it feels like to be pulled, like a ‘child of divorce’ between the bitter arguments between those advocating LGBTQ equal rights and certain oppositional, or simply ambivalent or absent, religious organisations. The return to the language of familialism here is interesting and awkward, given the discussion on the prevailing heteronormative frames of religion inclusion, as intersecting sexuality and gender. In terms of specifically lesbian involvement and leadership, the young women in the project were particularly concerned that the most viable role for women was as an ‘elders’ wife’ (see, Making Space for Young Lesbians in Church? Intersectional Sites, Scripts, and Sticking Points)

Despite this, there were many ways in which young people ‘made space’ for religious and sexual identities in creative and meaningful ways. For example, young people creatively claimed space online, in social media forums and through using digital technologies, ‘coming out’ as queer and religious (see, Taylor, Falconer, Snowdon 2014). Rather than online technologies creating difficulties and unwelcome exposure, many young people use these spaces to activity negotiate, question and shape sexual-religious identification. Such engagements often act as interactive resources, through which young participants (re)gain control over their identity profiling (e.g. on Facebook pages), and provides a ‘virtual space’ to be both religious and queer, against the restriction of offline spaces (‘I just said it on Facebook, typed in ‘I’m gay’ and I hit ‘enter’). One interviewee, for example, mentioned the ‘picking up’ of personal-public information as replacing a face-face ‘coming out’ moment: ‘He’s [her brother] probably picked it up, like I’m on Twitter and I think that’s part of my description, so he’d be a bit dim if he hadn’t picked it up by now but he just hasn’t mentioned it’. When much has been mentioned about the disconnect between ‘religion’, ‘sexuality’ and ‘youth’, from policy formation to media reporting, and academic ‘wrestling’, the project hopes to continue to consider the co-existence and lived-in realties of queer and religious identities.

Yvette Taylor and Emily Falconer are members of the Weeks Centre for Social and Policy Research at London South Bank University. Read more on the policy impacts of Making Space for Queer Identifying Religious Youth: Politics, Policies and Public Imaginations. The title for this article is borrowed from Jodi O’Brien.