Michael Rosie (University of Edinburgh)

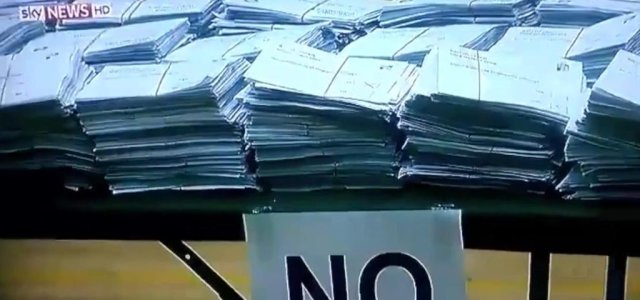

On 18th September Scotland said ‘No’ in its independence referendum. Yet therein lies a tale, for there are five remarkable things about Scotland’s independence referendum that bear reflection. The first was the extent of democratic engagement and participation: 85% of those registered to vote actually turned out to do so. Let’s put that in some kind of context: only two UK general elections since 1918 had turnouts exceeding 80% (1951, 1955), and the highest previous referendum turnout in the UK was the 81% who came out to participate in Northern Ireland’s 1998 referendum on the Good Friday Agreement. The 1998 and 2014 referenda were unusual: the Common Market referendum of 1975 offers the highest UK-wide referendum turnout – 65%.

But there is more. In 2014 an unprecedented 97% of those eligible to vote in Scotland registered to do so. What we have just seen in Scotland is a remarkable democratic engagement across class, across gender, and across region. The debate over independence did not just exist in our morning newspapers or in the set piece televised debates in which political leaders shouted and pointed at each other. You could hear, and participate in, referendum talk on the buses and trains, in post office queues, in shops and pubs and football grounds. A slow burning debate, which began almost as soon as the dust of the 2011 Scottish election had settled, burst into life around February as hitherto rather static polls – suggesting a clear ‘No’ lead – began to narrow.

And it was the last six months or so of the campaign that saw the second remarkable thing: a grassroots activism that spanned far beyond the confines of ‘official’ campaigning. This was very much a one-sided affair. Whilst the ‘Better Together’ campaign (a platform shared by the three major UK parties in defence of the union) was fairly sluggish on the high street and in canvassing housing estates, pro-independence activism expanded dramatically. Whilst much of this was focussed around the official Yes Scotland campaign, much else centred around the Radical Independence Campaign (RIC – an umbrella collective of radical and green activists), and groups such as Women for Independence, Academics for Yes, Business for Scotland, and the artists and writers of National Collective. These pro-independence groups were adept at utilising social media and of giving the clear impression (sometimes true, but sometimes usefully and artfully spun) that it was the Yes side where you would find the passion, the commitment and the energy.

By contrast, Better Together leaflet drives – or Scottish Labour’s Referendum Battlebus – seemed at times downbeat and undermanned, and at others as contrived and rather superficial media stunts. Such interpretations may have been unfair or inaccurate – there were stunts on both sides – but there was a clear sense that the campaigning ‘buzz’ and ‘substance’ was very much with Yes. Better Together could be their own worst enemy. With RIC spearheading voter registration drives in Scotland’s most deprived and politically alienated housing estates, one senior ‘No’ strategist reportedly sneered that “people with mattresses in their gardens do not win elections”. In football parlance, this was a quote from the other team to be pinned to the dressing room wall. With the polls continuing to close it began to seem that all the momentum lay on the Yes side of the debate, and Better Together appeared to have little by way of substantial response.

By Spring it was clear – at least to those paying attention – that the unionists were in trouble. Opinion polls continued to narrow and suggested a public wearying of a relentlessly negative No campaign (apparently privately dubbed ‘Project Fear’ by Better Together strategists). Better Together announced a new emphasis on the “powerful, positive case” for continued union. This was that Scotland could enjoy The Best of Both Worlds: remaining within the security and stability of the United Kingdom whilst enjoying “a Scottish Parliament with more powers guaranteed”. Strikingly, few in the media queried this ‘guarantee’ of more powers even though Better Together were vague on specifics beyond legislation already on the statute books. It was clear that there was little agreement between (or within) the unionist parties on what further powers would, or could, be given to the Scottish Parliament in the event of a No vote in September. Nor was there any detail on the mechanics of how Westminster legislation on these powers would be achieved, and how the concerns of MPS – not least those representing English constituencies – would be addressed and assuaged.

Some of this may have shown, since the polls continued to narrow until, less than a fortnight before the vote, YouGov for the Sunday Times put Yes ahead. Discounting the undecided, YouGov found 51% of Scots would vote Yes, and 49% No. Although the Yes lead was well within the realms of sampling error the poll set loose what seemed to be a rather ferocious cat amongst some rather unprepared pigeons. Better Together gave off the clear impression of utter panic. Cameron, Clegg and Miliband embarked – separately – for Scotland to rally the cause. So too did Gordon Brown. It became quite unclear who was leading the Better Together campaign –Darling, the campaign’s formal and rather bureaucratic head, Cameron, a UK Prime Minister deeply unpopular in Scotland, Miliband, leader of UK Labour, or Brown, former PM and now backbench Labourite. By this stage leaders of the Scottish LibDems and Scottish Labour seemed missing in action, or seriously sidelined by their Westminster counterparts. Only Ruth Davidson, the leader of the Scottish Conservatives – a rump party in Scotland down to its bare electoral bones since 1997 – seemed to give any kind of a ‘Holyrood’ profile to the No side.

To the third remarkable thing, then. Two days before the Referendum the UK party leaders signed The Vow, published on the front page of Scotland’s Daily Record. The chosen outlet is significant –the Record remains tabloid of choice in Labour’s Scottish heartlands, and suggests fears over the loss of a significant portion of the Labour vote to the Yes side. The Vow is a truly noteworthy piece of text. In it the three leaders commit to the following:

The Scottish Parliament is permanent and extensive new powers for the parliament will be delivered by the process and to the timetable agreed and announced by our three parties, starting on 19th September. […] People want to see change. A No vote will deliver faster, safer and better change than separation.

Take a moment to consider the implications: under pressure from Yes, the unionists shifted from their rather vague, and potentially empty, ‘guarantee’ of further powers to Scotland after a No vote. Now they conceded Holyrood’s permanency and that new and extensive powers would be delivered within a highly ambitious timetable. In just two weeks, the Yes campaign had wrestled from the UK Government and Opposition a commitment to far-reaching constitutional reform. Compare that to the constitutional reforms won by the Liberal Democrats in over four years of formal coalition with the Conservatives.

Equally remarkable, however, is the immediate political detail since the Vow qualitatively shifted the meaning of the referendum. In the Edinburgh Agreement of 2012 the SNP had pressed for a multi option referendum offering independence, the status quo, or substantial further powers for Scotland. The third of these was blocked by the UK government in favour of a straight Yes/No on independence. With the Vow the unionists conceded that “People want change …” The referendum was thus now the vehicle for that change: were further powers to be delivered through independence, or within the United Kingdom? The original second option, no change, was now officially off the table with just two days to go. After the Vow ‘No’, after all, would not mean ‘No’.

Just what the unionists did now mean by ‘No’ remained unclear. Various hares went running: ‘devo max’, a federal solution for Scotland, even a federal UK. Strikingly few UK commentators took note that the Vow challenged a key principle of Constitutional tradition: the indivisible sovereignty of the Westminster Parliament. If Holyrood is to be permanent then the principle that ‘power devolved is power retained’ no longer holds. The sharing of formal sovereignty is not, of course, unthinkable – in practice sovereignty is already variously shared at local, sub-state and supranational levels – but such a clear challenge to Constitutional tradition will spark considerable debate, and perhaps disquiet on the backbenches. And it is through the backbenches of Westminster where the Vow –like any other formal parliamentary business – must be delivered. The Vow, after all, was pledged on behalf of a Parliament not yet consulted. Even before the polling stations opened there were rumblings from within both major UK parties that did not bode well for how deliverable their leaders’ commitments actually were.

The fourth remarkable thing is that despite Project Fear; despite a mass media overwhelmingly hostile to Scottish independence; despite recurrent smears that Yes supporters were deluded, overly romantic, even orchestrating ‘mob rule’; despite all of this, 45% of Scotland’s voters favoured leaving the United Kingdom. That alone represents a striking verdict on a 307-year union in which the Scots have often enjoyed a good deal of, often informal, autonomy. It also speaks volumes for the way that the debate developed and the real (and quite delicious) uncertainty right up to the result as to which side was going to win. This seemed to perplex many commentators – particularly those in a London-centric media – who had long dismissed the prospects of the Yes side, not least through a profound misunderstanding of pro-independence sentiment. A UK media focus on Alex Salmond and his SNP obscured rather than informed. Yes mobilised voters across the political spectrum, and amongst those normally indifferent towards or alienated from electoral politics. A substantial amount of polling and survey evidence – collated, analysed and made accessible by the excellent What Scotland Thinks website – illuminates widespread support for independence amongst Labour supporters, across class and religion, amongst ethnic minorities and ‘new Scots’, and across region. Any notion that this was a narrowly ‘nationalistic’ movement was quickly disabused through actual contact with it. It was young, vibrant, energetic, pluralistic and very ‘civic’ in its orientation.

Any notion that 2014 settles the Scottish Question should also be set aside. Even before the poll it was clear that a No vote would raise almost as many questions as a Yes. The onus is now on the Westminster parties to deliver upon their Vow. Yet we have already seen stirrings of revolt on both Conservative and Labour backbenches. In his response to the referendum result, Cameron promised not only further powers to Edinburgh, but also proposed wider changes in the way that the various territories of the United Kingdom are governed. On the face of it, this was a neat manoeuvre: it spoke to territorial concerns beyond Scotland and seemed to address the West Lothian Question, the ‘anomaly’ of Scottish parliamentarians (many forget the Welsh and Northern Irish MPs in similar positions) being able to vote on purely English matters, long a bugbear for English Conservatives. ‘English Votes for English Laws’ (EVEL) is dismissed by Vernon Bogdanor as a “logical absurdity” through which a UK Government might deliver its UK-wide manifesto commitments, but fail to command a majority on its policies for England.

But EVEL’s logic is tactical rather than constitutional, since it allowed Cameron to snipe towards UKIP on Englishness and to wrong foot Labour in advance of the 2015 UK general election. Labour has, hitherto, been the party of constitutional change having delivered the legislation that enabled devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in the late 1990s. Labour is also, significantly, the party with most to lose in Scotland should the post-dated cheque of the Vow bounce. Cameron can portray himself to English voters, somewhat disingenuously, not only as the Prime Minister who saved the union, but the Prime Minister who will redraw and buttress the union more widely and wisely for generations to come.

There are dangers on all sides. First, Cameron’s hastily sketched pan-UK vision hardly augurs well for speedy delivery of more powers to Scotland. Any inkling of unreasonable delay on delivering on these vows and guarantees is likely to seriously reignite the Scottish Question. The dangers in that are primarily to Labour, not only in the UK election of 2015, but especially in the Scottish election of 2016. Scotland may well have voted No, but opinion polls – admittedly at long range – suggest the return of an SNP government. Perhaps more ominously, Scotland’s referendum prompted heightened sensitivities in Northern Ireland: Unionists feared a major weakening of the UK; Republicans saw the referendum as a boost to their campaign for a Border Poll. With post-‘98 arrangements already under serious strain, any constitutional discussion – let alone reform – in Northern Ireland demands the careful and sensitive investment of time and negotiation that Scottish urgency (and the Vowed timetable) makes difficult.

Lastly – and perhaps most intractably – is the issue of redrawing the governance of England, for it is not at all clear that the English electorate see any need at all to change their structures of government. A federal or quasi-federal approach – which would offer a constitutional symmetry missing at present – demands either strong regional legislatures in England (for which there is little, if any, appetite) or a dedicated English Parliament. The latter is hardly attractive since most voters in England – for perfectly understandable reasons – already see Westminster as their Parliament. That makes EVEL, in some shape or form, the ‘easiest’ route to pursue – one especially easy for the Conservatives given that it would act to hamstring Labour’s Parliamentary muscle. The exclusion of Scottish MPs would reduce the Labour whip on English issues by 41 and the Conservatives by just one. In short the sensitivities of Northern Ireland, and the understandable reluctance of the English to see the need for any substantial tinkering of their existing governance, call for calm, reflective and careful consultation on these issues rather than party political self-interest. Yet the time and flexibility available has been sorely limited by the guarantees, pledges, promises and vows made to Scotland during the referendum campaign.

There is more to come from the Scottish Question, which has mutated markedly over the last several months. And the Question – or rather how, if at all, it is now answered by Westminster – could provoke a fatal legitimacy crisis for the union. Scotland has long seen its place in the United Kingdom as based upon partnership. Excellent scholarship by, for example, Lindsay Paterson and Graeme Morton illustrates how the 1707 union allowed Scotland considerable autonomy over its own affairs. This produced, from c.1750-c.1950, a ‘unionist nationalism’ in Scotland which was self-consciously Scottish and proudly British. It is striking that Scotland offered no serious threat to the British state before the late 1960s: and this was basically because the union had guaranteed the continued autonomy of the basic building blocks of Scottish civic life. From 1707 the Scots retained their own systems of Presbyterian religion, of Scots Law, of education, and of local government. As state and society became more complex over the 18th and 19th century Scottish associational life expanded through Scottish institutions, buttressed and protected by the union partnership. Scotland was always ‘a place apart’, but this mattered little so long as the union worked to recognise and protect Scottish interests and there was simply no need to seek independent statehood. Indeed Scotland’s political nationalism until c.1950 was resolutely a Scottish variant of British nationalism.

It is no coincidence, therefore, that a separatist Scottish nationalism does not emerge in earnest until the decline of Britain as an economic and military power from the 1950s. The values often invoked in Scottish politics are remarkably similar to those evoked by the Keynes-Beveridge principles (or, perhaps, myths) of Britain’s post war decades. For many in Scotland it is ‘Middle England’ that has abandoned British values: hence the Thatcherite message, despite its hagiography of Adam Smith, garnered modest and rapidly reducing electoral returns in Scotland.

Labour’s response to a growing Nationalism was to increasingly flaunt its own ‘Scottish’ credentials. The SNP, all too aware that real progress necessitated advances in Labour’s urban heartlands, shifted to the left. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s there was a convergence in the style and tone of both the Labour Party in Scotland and the SNP: both entwined Scottishness with a rhetoric of (if not always a clear policy commitment to) social democracy. Whilst social attitudes in Scotland are not markedly different from those of England, and in particular Northern England, their political expression is highly distinctive. In England, even in the North, the key political battleground is centre-right versus centre-left. In Scotland, perhaps uniquely in Europe and beyond, the key battleground is the centre-left. This has left Scottish Labour weakened at points by their UK party’s playing of the Westminster game which, to Scottish social democratic eyes at least, is overly fixated on the whims of middle England.

Scottish nationalism is thus the dominant mood in contemporary Scotland – note however the lower case ‘n’. As Tom Nairn has pointed out, Scottish nationalist sentiments and impulses go far beyond the sphere of the SNP. Much of that nationalism operates, through the everyday institutions of distinctively Scottish life, in what Jonathan Hearn describes as ‘banal, personal, and embedded ways’. The point here is that Scottish Labour, the Scottish Liberal Democrats, and even the Scottish Conservatives are just as nationalist in their outlook as the SNP. Much of the unionist campaign, too, rather unwittingly undermined Scottish ideas of the union being a partnership. Many commentators have misread the significance of the issue of currency in an independent Scotland. Whilst it true that uncertainty over which currency the new state would use may have buttressed many on the No side, Westminster’s refusal to share Sterling in a currency union was skilfully used on the Yes side to demonstrate that the idea of partnership was not reciprocated.

Taking this ‘lower case’ starting point, it becomes easier to understand how the Yes campaign managed to attract, perhaps, as many as 40% of Labour supporters. More importantly, it also highlights that most on the No side were also deeply infused with concern for Scotland in a specific and national sense. The Vow, then, will be scrutinised almost as keenly amongst those who voted No as those who voted Yes. Failure to deliver on these commitments in good time will be seen as a betrayal by many on both sides, and will seriously reignite the question of Scottish independence. Winning in 2014 by promising the undeliverable may well cost the unionists their union.

2014 offers challenges and opportunities for social science. It is likely that Constitutional Change will be a key battleground in UK politics over the next several years, and the ESRC in particular has a good record in funding serious enquiry into this since c.1999. But the challenges and opportunities may well focus on the fifth remarkable thing about Scotland’s referendum. In the immediate aftermath of the No vote the key parties on the Yes side reported unprecedented increases in membership. Within a week of the referendum the membership of the SNP soared from under 26000 to over 65000, easily overtaking the LibDems as the UK’s third largest party. The Scottish Greens rose from 2000 to 6000 members the same week, with increases also reported by the pro-independence Scottish Socialists. The re-energising of the Yes campaign so quickly after the disappointment of Thursday 18th September was, in the words of a leading Scottish columnist, “a very strange development which no-one could have forecast”.

Despite having lost the referendum, the Yes side appear more like the victors – on a roll and building up political momentum. But what exactly is this phenomenon? A campaign? A movement? A rebellion? Where exactly is the ‘divided nation’ that Cassandra voices in the UK media predicted? Can the Scottish parties harness this incredible outburst of democratic participation and, if so, to what purpose? Whilst the eyes of the UK political media have, all too predictably and rapidly, returned to their Westminster soap opera something unusual is brewing in Scotland. How it develops and where – if anywhere – it leads may have profound consequences for both the future of the UK and in our understanding of political participation in modern democracies.

Michael Rosie is Senior Lecturer in Sociology, University of Edinburgh. Until August 2014 he was Director of the Institute of Governance a key hub for research on identities, nationalism and territorial politics. In 2014 The Institute set up the Scottish Government Yearbook Archive, which he maintains.