Robert Grimm (Manchester Metropolitan University) and Marius Guderjan (Humboldt University)

Eurosceptic parties across the EU have never been more successful than in the 2014 European Parliament elections. The UK Independence Party’s landslide victory with over 27 per cent caused a political storm. For the first time in modern UK history, neither Labour nor Conservatives have won a national election. In Germany, a traditionally Europhile nation, the Eurosceptic Alternative for Germany (AfD) made substantial gains and received over seven per cent of the vote.

Whilst the AfD’s success was nowhere near as big as that of the UKIP or the French Front National, it is the first time in Germany’s history that a Eurosceptic party received such support.Since the end of the Second World War, Germany’s state identity has traditionally been associated with further European integration, patriotic sentiment has often been stigmatised as neo-Fascist. Indeed the dictum has always been to make Germany more European rather than Europe more German. However, German re-unification and demographic change, the increasing withdrawal of the war and first post-war generation from public life, may have contributed to a revaluation of Germany’s collective identity. Perhaps the vote for the AfD is indicative of the internal pressures to recalibrate the country’s foreign politics to pursue national rather than European interests more vigorously.

The position of young people towards the EU is ambiguous. The AfD is particularly successful in mobilising young followers. Sixty-three per cent of AfD supporters are under the age of 30. According to a study by YouGov, UKIP draws its support predominantly from older voters. Data from MYPLACE, a research project examining the social and civic attitudes and engagement of young people across Europe, provide detailed insights into the views of young Germans and Britons towards the EU.

Germany benefits from the EU

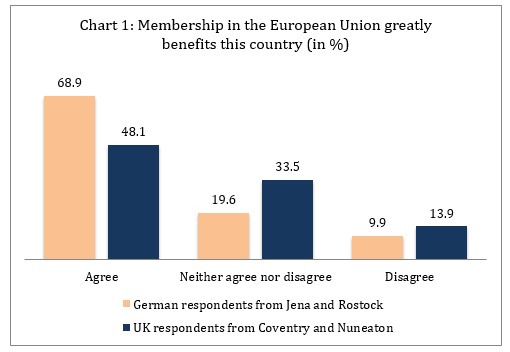

Our study found that young people in East Germany believe that the EU is advantageous for Germany. Only ten per cent of those interviewed disagree with that view (Chart 1). In addition to economic benefits young people value peace, solidarity, a common culture and currency as well as the freedom of movement within the EU, which provides them with the opportunities to live and work in other countries without restrictions.

Young Germans also see the EU as a positive input for their personal future as well as a source for cultural stimulation and innovation. Thus, for many young Germans, the EU continues to have multi-faceted utilitarian value. Udo an 18 year old apprentice from Rostock thought that,

‘Germany benefits from the common currency, because whoever wants to travel to another country doesn’t have to exchange money…Particularly, freedom of trade and travel are the biggest advantages that you’ve got.’ Udo, 18, apprentice in Rostock

Tina on the other hand feared that without the EU Germany might again turn into an authoritarian regime

‘If Germany wasn’t part of the EU, it would be an independent state and something would go wrong again and we would get a dictatorship. It’s very important that we’re in the EU and that if something goes wrong, the other countries can immediately counteract.’ Tina, 18, apprentice in Rostock

Jens, a student from Jena, saw in the Union a great opportunity for cultural exchange

‘It has personally become easier to study or live in another country. Germany benefits from the EU by getting new input in terms of culture and politically.’ Jens, 24, student in Jena.

Germany’s crisis management

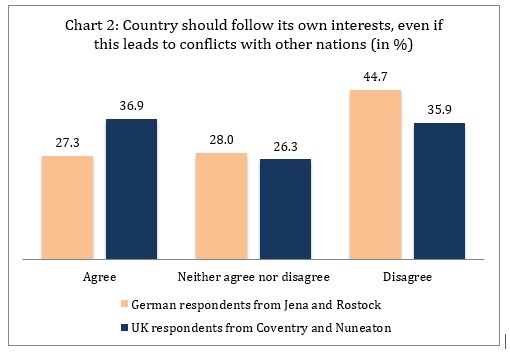

As the EU’s largest economy and biggest contributor to European bailout funds, the European sovereign debt crisis put Germany in a peculiar situation. Germany is committed to European integration and expected to show leadership. However, strategies to overcome the crisis have to accommodate European socio-economic diversity and ask for measures that are in conflict with Germany’s national political and economic priorities. Young people are aware of Germany’s important role in Europe. Many of them strongly believe that Germany should act responsibly and not unilaterally to safeguard the future of the Euro and the Union. Almost half of the interviewed do not think that Germany should follow its own interest if it clashes with the interests of other countries (Chart 2).

Solidarity with troubled states

MYPLACE respondents in Rostock and Jena support cross-European solidarity and Germany’s contribution to European bailout funds rather than a breakup of the EU. Johanna, a 23 year old apprentice in Jena did not want to ‘kick out a state, just because it becomes inconvenient.’ And Peter said that,

‘Germany is a country that carries Europe but it is also carried by Europe. An EU without Germany and a Germany without the EU, neither would work out.’ Peter, 21, student in Rostock

In some Member States, Germany’s take on the crisis has evoked uneasiness. Bailouts have come with strings attached and the Merkel administration stands for austerity measures hurting citizens in affected nations. This did not go unnoticed among young Germans. Interviewees like Judith and Linda expressed discomfort with Germany’s dominant role which they believe undermines European ideals.

‘I know of many people in Greece who are against Germany because they’re always coming up with austerity measures. And some countries perceived this dominance as disproportional.’ Judith, 19, pupil in Jena

‘If it’s all about who owns whom and who’s got the say, it’s against the European idea which was originally built on reconciliation between European nations at enmity.’ Linda, 24, student in Jena

Scepticism towards financial bailouts

Despite the pro-European attitudes, the crisis has been a test for German solidarity with weaker Member States. It is easy to make commitments when the German economy is thriving but public attitudes can change when confronted with negative outlooks. A considerable number of respondents are concerned about future fall-outs from the crisis and they advocate a foreign policy that is skewed towards national German interests. Just under one third of our respondent thought that Germany should pursue its interests even if these conflict with the interests of other countries. Emil sums this up nicely,

‘Sometimes the German government should look a bit more after Germany. Sometimes it’s the case that we invest so much into Europe that the own population falls a bit by the wayside.’ Emil, 16, pupil in Jena

Young Eurosceptic Britons

For young British respondents in Nuneaton and Coventry, EU membership appears to offer few opportunities. People in Nuneaton, in particular, are deeply sceptical. Many see the EU as an imposing (‘dictating’) external threat and a source of unwanted interference that is undermining the integrity of British identity and sovereignty. Or, as Craig (25 unemployed Nuneaton) suggests,

‘the EU overturn everything man, do you know what I mean? I think we should have a lot more control over our, control over our own policies, instead of like oh well, we’ll have to look at the EU for this, oh, we’ll have to look at them for that…’

Most importantly, the EU is also seen to divert attention away from burning domestic issues. As 19 year old single mum Beth, from Nuneaton, points out Britain should leave the Union because ‘then you can actually start listening to your own people instead of some different country’. Indeed leaving the EU is perceived to be a ‘brilliant’ solution for labour market competition between the British population and Eastern European migrants ‘because then the British have more jobs’. Rather than supporting EU bailouts, the UK government should focus on much-needed local social and infrastructure investments. For Craig it is unjust that ‘We’re paying for Spain’s roads. What have we had? Look at our roads’ and Cara (19 an electrical apprentice) believes that it is wrong that Britain is ‘all too ready’ to give financial support to Ireland and Spain since there is ‘a hell of a lot of children and families living under the poverty line’ in the UK.

Young Britons in UK MYPLACE case study areas perceive the EU as a distant and an elitist project. Discussions about EU membership quickly turn into a debate about class. Cara suggests that European migrants are not taking the doctors’ jobs and the civil engineer jobs ‘the upper class jobs, as it were, so I think it’s quite, it’s seen quite as an issue that working class people care about and not really anybody else’.

For young Britons in Nuneaton and Coventry exiting the Union may present itself as the lesser evil. According to Felix (18 A level student), Britain would lose income from trade but the UK would also save its contributions to the EU budget. In the eyes of the young soldier, Barry, Britain is self-sufficient and can stand on its own feet ‘all we’d have to do is get the ports back up and running properly again, do you know what I mean, go back to how it used to be …’

Pro-European Germans anti-European Brits?

Young Germans in Jena and Rostock have a positive perception of the EU. Many see personal and national utilitarian value in European integration, others also have an emotive attachment to the EU and ‘feel’ European. First hand experience of World War II is fading, young people have grown up in a unified Germany and thus they take peace and freedom for granted. The political need for a Europeanised German identity moves increasingly into a distant past. Young Germans may therefore be more critical of European integration. MYPLACE data confirms some scepticism about Germany’s support for struggling European member states. There are concerns about the extent to which Germans have become liable for ‘other peoples debt’. This may explain why the Eurosceptic AfD was able to mobilise young voters.

Nonetheless, support for the AfD is still marginal. Most young Germans believe that solidarity with weaker member states is also in German interest and are therefore sympathetic towards bailout politics. Britons in Coventry and Nuneaton do not share young Germans’ predominantly positive outlook on European integration and the need for European solidarity. They see neither utilitarian value in EU membership nor do they ‘feel European’. Rather, the EU is understood to be an elitist project and an external threat. In many respects, the EU is a scapegoat for failed British social and economic policies and draws much needed resources away from local communities. However, the picture is not as black and white as it seems. Despite their scepticism, nearly half of MYPLACE respondents in Nuneaton and Coventry believe that the UK greatly benefits from EU membership and only just under 14 per cent disagree (Chart 1).

Robert Grimm is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Manchester Metropolitan University and member of the Policy Evaluation Research Unit. Marius Guderjan works at the Centre for British Studies at Humboldt University of Berlin. Marius and Robert currently research political attitudes and civic engagement among young people in Europe. The research reported here is part of the pan-European FP7 project MYPLACE, grant agreement no. 266831. Hilary Pilkington (Manchester University) coordinates the Project. The findings reported here are based on a representative quantitative survey in the two East German cities of Jena (N=608) and Rostock (N=608) as well as Coventry (N=542) and Nuneaton (N=550) in the UK. Thirty in-depth semi structured interviews were conducted in each research location. The data was collected between October 2012 and May 2013. MYPLACE respondents were aged 16-25 at the time of the interview.