Sarah Turvey, University of Roehampton

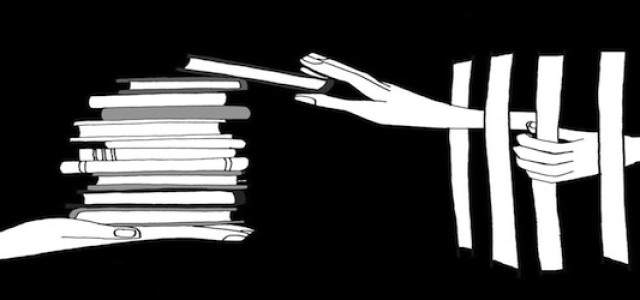

The Justice Secretary recently created a near-perfect storm of protest over what has become known as his prison ‘book ban’. His action and the response it provoked raise important questions about the role of reading in rehabilitation and what books can do behind bars.

Last November Chris Grayling signed off a Prison Service Instruction that bans prisoners from receiving parcels, including those containing books. In March Frances Crook, chief executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform, wrote a blistering attack in Politics.co.uk, concluding that ‘punishing reading is as nasty as it is bizarre’. Crook’s piece was widely reported and led to an authors’ protest outside Pentonville prison in North London and a postcard campaign by writer members of English PEN. Grayling defended the instruction on the website’s Comment section on the ground that all prisons have libraries to which prisoners have guaranteed regular access, whereas parcels and the books they may contain are privileges. If prisoners want their own books, they should have to buy them with money earned in prison.

Grayling insisted: ‘Of course, this government believes that access to books is vitally important to literacy, education and training. And yes, of course we want to encourage prisoners to read, and to read more’. He could hardly have said anything else. What is needed is a more widespread debate about what education in prison ought to do, how it can contribute to rehabilitation and what part books play in the process.

Funding for prison education has become increasingly tied to easily measured outputs in the form of accredited courses. Many of those on offer are necessarily basic ones for prisoners who lack literacy and numeracy. The Prisoners Education Trust extends provision with a grants programme which assists prisoners to study distance learning courses in subjects and levels not available in prison. In addition, there is some informal learning provided largely by voluntary organisations, many of which offer arts interventions from dance and drama to creative writing and reading.

The Prisoners Education Trust and umbrella organisations such as the Prisoner Learning Alliance and the Arts Alliance argue for closer alignment of prison education with the goals of desistance and reducing re-offending, particularly through greater emphasis on helping prisoners to create new identities for themselves and new connections with others. This is very clearly laid out in the PLA’s 2013 report, Smart Rehabilitation

The Prison Reading Groups project (PRG) was established in 1999 to help set up and run informal reading groups in prisons, and currently supports over forty groups in more than thirty prisons nationwide. Its 2013 report, What Books Can Do Behind Bars, provides evidence of the power of books to contribute to this wider education agenda.

Much recent thinking about going straight sees it not as a single event but as an ongoing process of not offending, of desisting from criminal activity. Desistance theorists stress the importance of offenders being able to create new ‘pro-social’ identities for themselves to replace that of ‘the criminal’. As part of the process they need to be able to act out these new identities and create new social networks. As Shadd Maruna puts it: ‘Identity is very much shaped within the constraints and opportunity structure of the social world in which people live’ (1). A prison reading group provides a space where the pro-social identity of ‘reader’ can be asserted and tried out.

One young man’s story illustrates this clearly. When he first joined the group he seemed uneasy and reluctant to contribute. But he stuck with it and was eventually persuaded to submit a review to Inside Time, the national prisoners’ newspaper. It was printed and he reported at the next meeting that it had been read and commented on by people throughout the prison. Better yet, his mother had been able to read it online and had told him how pleased and proud she was. For him, books, the reading group, and his review cemented his new identity as a reader: someone who is able to read, discuss and even write about books.

Reading fosters empathy and imaginative capital, the ability to imagine and experience what it feels like to be someone else. And this is what the philosopher Martha Nussbaum sees as the vital importance and public good of an education in the humanities: that they ‘make a world that is worth living in, people who are able to see other human beings as full people, with thoughts and feelings of their own that deserve respect and empathy, and nations that are able to overcome fear and suspicion in favour of sympathetic and reasoned debate’ (2).

Prisoner discussions of books confirm the power of empathy. A sixty-year-old white woman responded to the twenty-year-old Bangladeshi woman in an arranged marriage in Raphael Selbourne’s novel Beauty: ‘I found the book gripping and felt the issues raised in the book topical but very disturbing. I tried to put myself in the position of Beauty or any other person in this position, an intolerable situation. It’s easy for most of us to say to person in this position. Leave home – get away. But how can you leave with nowhere to go – no one to support you – no money…’ (3)

Official prison strategy also wants to get prisoners thinking about the situations of others, and about the consequences of actions. Prisons offer a range of offending behaviour courses, and completing one or more of them may be required if a prisoner is to be considered for early release. The problem with some of these courses is that they do not always engage the imagination. ‘I know what I’m supposed to think’ is how one prisoner put it. And this view is backed by criminologists such as Fergus McNeill who refers to the ‘overly-scripted, manualised, homogenised approaches’ (4) of these cognitive behavioural interventions. The power of literature, by contrast, is that you don’t always know what you are supposed to think. Indeterminacy becomes the spur to meaningful critical and moral judgements.

The most powerful books are often those that encourage empathy but also ask the reader to step back from it, even to resist it, in favour of critical distance and judgement. For prisoners especially this can be challenging. As one prisoner reader discovered: ‘At school I identified with Billy when I read A Kestrel for a Knave. But when I re-read it in prison, I realised I was more like his brother Jud, the bully.’Alexander Masters’ Stuart: A Life Backwards tells a true story of childhood abuse, disability, drug addiction and eventual death. One reader summed up his experience of the book very directly; ‘Good but close to home’. Despite this, what he and other readers went on to explore together were the limits of identification and the need to take responsibility, whatever the disadvantages of background or upbringing.

Reading and group discussion also develop vital employability skills: how to argue and reflect critically on one’s own views and those of others; how to negotiate meaning and make decisions.‘[In the book group] my opinion is valid, I am listened to and others care what I say. In the book group everyone is given a voice, all have an equal say.’

‘It’s a real joy to be able to disagree and remain friends afterwards.’

Books can also create and strengthen family connections, one of the key pathways to rehabilitation recognised by the National Offender Management Service (NOMS). A book sent in to a prisoner (before Grayling’s ban) could be a useful icebreaker at a visit or a subject for a letter or a phone call: ‘Before coming to prison I never read much. My partner does and she suggested I join the prison reading group. Now I even pass the books on to her.’And, ‘My daughter is doing English and I have been able to discuss things with her; the reading group gives me pointers for how to discuss books.’

Books and reading also foster a sense of connectedness with readers outside. The paradox of prison is that it cuts prisoners off from the society it is preparing them to re-enter. An important first step towards rehabilitation and renewed citizenship is the recognition of community with strangers, of having shared interests with people you will never meet. This was well demonstrated by the experience of a men’s prison reading group who read Marina Lewycka’s A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian. The group were intrigued by the author’s account in a Guardian article of her visit to an all-women’s group outside. On the face of it, the two groups had very little in common. But the men really wanted to know how these unknown women had responded to the book and its characters. To find out, they wrote to the women’s group and an exchange of views followed for several months.

The widespread coverage of Grayling’s ‘book ban’ is useful. If it can help spur a debate about the means and ends of prison education it could prove invaluable.

References

Maruna, S. (1999) ‘Desistance and Development: The Psychosocial Process of “Going Straight”’, British Criminology Conferences: Selected Proceedings, M.Brogden (ed.) Volume 2, March 1999.

Nussbaum, M. Not For Profit, Why Democracy Needs the Humanities. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Hartley, J. and Turvey, S. (2013) What Books Can Do Behind Bars. London: University of Roehampton. [All further prisoner quotations are from this publication]

McNeill, F. (2012) ‘Four Forms of “Offender” Rehabilitation: Towards and Interdisciplinary Perspective’, Legal and Criminal Psychology. 17:1

Sarah Turvey is a member of the Department of English and Creative Writing at the University of Roehampton and is co-director of Prison Reading Groups (PRG).