Cecily Jones, Independent Researcher

Fourteen heads of Caribbean governments recently gathered at a summit in St. Vincent and the Grenadines to discuss a range of pressing regional issues, such as economic insecurity, crime, unemployment, homelessness, sex trafficking, domestic violence, drugs, climate change and disaster preparedness. But the issue that caught the attention of global media was the proposal to develop a plan to seek reparations for crimes against humanity committed by former European slave trading states. The group calls on the former colonial powers to acknowledge their historic culpability, recognise the continued legacy of colonialism and slavery and commit to a reparatory social justice programme of restitution for the genocide of the region’s indigenous peoples, the transatlantic slave trade, and the enslavement of millions of Africans peoples over four centuries of European colonialism.

Specific demands include: 1) A full formal apology; 2) A programme to resettle those persons who wish to return to Africa; 3) Aid to alleviate the high incidence of chronic diseases which the Caribbean claims is a direct result of the “nutritional experience, physical and emotional brutality, and overall stress profiles associated with slavery, genocide, and apartheid”; 4) Illiteracy eradication; 5) Debt cancellation.

The group seeks to link the region’s current malaise to the history of slavery and colonial rule in a strategy that they believe will strengthen their claim for reparations that should become part of a new development agenda for the region.

The Caribbean rarely attracts much media attention outside the region so the global coverage given to CARICOM’s proposal indicates the significance of the current push for reparations. The implications for the former colonial powers are enormous, as litigation could see each of them making multi-million dollar payouts. It could also set a precedent for other claims for reparations. Most commentators agree that transatlantic slavery was a brutal, inhuman, degrading and indefensible atrocity. Nevertheless, few believe that CARICOM’s proposal stands much chance of success.

A brief outline of contemporary reparations movements

Reparations for the historic injustices perpetrated against Africa and enslaved African peoples is not a new concept and the current movement is rooted in a centuries old tradition of black radicalism and resistance. Enslaved peoples devised resistance practices that ranged from intransigence, go-slow, sabotage of plant and machinery to all-out rebellion, the most successful of which was the Haitian Revolution which overthrew the French plantocractic regime and saw that island become the first Black republic in the modern world and paid a severe ‘price’ for doing so. Following the successful revolution in 1804, Haiti was forced to compensate France in the sum of 90 million gold francs for loss of its territorial ‘rights’. Despite Haiti’s extreme fiscal problems, from 1825 to 1947 the Haitian government struggled to maintain payments to France, facing the threat of gunboats and economic sanctions (Haiti’s reparations suit in 2003 for 20 billion Euros – the modern equivalent of the sum paid by Haiti – was summarily dismissed by the French government in 2003, which countered that France had already supported the Republic with millions of dollars of aid).

After emancipation, formerly enslaved peoples and their descendants across the African diaspora articulated individual and collective grievances over the persistent suffering in abject material conditions little better than those pertaining during enslavement. The first tentative demands for reparations can be identified in the radical intellectualism of pan-Africans such as Edward Wilmot Blyden (1832-1912); Marcus Garvey’s Pan-Africanist Black Star Liner movement; and black leaders and movements from Martin Luther King to Rastafarianism and the Nation of Islam. All have argued that reparations are an essential condition for the economic, political, social and cultural progress of the descendants of the formerly enslaved. Reparations in this context include repatriation to Africa and the return of cultural artefacts taken from Africa and now housed in European and US museums.

For decades reparations largely disappeared from national and international agendas. Then in the 1990s activists took inspiration from the success of other campaigns for reparations. These included Jewish Holocaust victims; Japanese people interned in the USA during World War II; indigenous peoples in Canada, New Zealand and the US; and Korean ‘Comfort Women’ forced into prostitution for the Japanese military. These, and other human rights triumphs, gave the impetus to Africans across the diaspora to rekindle debates and claims. In 1992, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) formed and mandated a Group of Eminent Persons (GEP) to explore a proposal by the Jamaica-based human rights lawyer Lord Anthony Gifford for a representative body with a mandate to claim reparations on behalf of all Africans who continued to suffer the consequences of the crime of mass kidnap and enslavement.

At the 1993 pan-African Conference hosted by Nigeria an official proclamation referred to the ‘moral’ debt and ‘the debt of compensation’ owed to Africa by those nations that engaged in and profited from transatlantic slavery, colonialism and neo-colonialism. In the same year, Bernie Grant, then MP for Tottenham in London, founded the African Reparations Movement, and put forward a motion in the House of Commons demanding that the issue of Reparations be debated.

In Sept 2001, the movement gained further momentum following the United Nations-sponsored World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance held in Durban, South Africa where the issue of reparations was raised. Disappointingly for those nations pursuing reparations, the former slave-owning powers argued that transatlantic slavery should have been a crime when it occurred, but in fact, it was not, so claims for reparations had no legal validity. In seeking to close down international dialogue, dissenters actually fostered a renewed commitment to the social justice imperative of reparations among the descendants of the formerly enslaved.

Durban represented a turning point, revitalising grassroots activism among African and diasporic African communities to develop frameworks to legally pursue reparations claims. That Barbados hosted the first follow-up to the Durban conference, the Afrikan and Afrikan Descendants World Conference against Racism in October 2002 was indicative of the growing strength of the reparations movement in a region in which it had largely been ignored.

The glut of commemorative activities that occurred throughout 2007 to mark the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade generated renewed debate about abolition and emancipation and the legacy of colonial slavery. Across the region National Reparations Committees were established to develop a road-map towards a unified CARICOM-wide proposal, followed in 2013 by a meeting of the first regional Caribbean Reparation Commission to drive the region’s position on reparations. This culminated in the proposal agreed at the March 2014 CARICOM meeting.

So what’s old and what’s new about the current claims for reparations?

Until recently, lack of regional consensus precluded a unified approach to campaigning for reparations, but the movement has grown apace, and now grassroots and official voices constitute a regional reparations movement. To be sure, the issue of reparations is “fractured, contentious and divisive” as a local commentator opined. Some respond with indifference, while others reject the very idea of reparations. Yet the issue of reparations refuses to go away, and excites considerable public interest, especially among those concerned with issues of social justice, equity, civil and human rights, education, and cultural identity. A local observer notes that, “The reparations discourse has been shaped by the voices from these fields as they seek to build a future upon the settlement of historical crimes”.

The issue of reparations is now considered by Africans across the diaspora to be one of the major human rights concerns of the twenty-first century. Caribbean students can even pursue an MA in Reparation Studies at the University of the West Indies. Conversely, neither European nor American governments appear willing to engage in dialogue with reparationists. The 2013 release of the Oscar winning adaptation of Solomon Northrup’s literary masterpiece 12 Years a Slave, exposed global audiences to the horrors of enslavement and has reinvigorated global conversations about slavery and its legacies, helping to make reparations just that bit more achievable.

Caribbean reparationists have historically grounded their case on the region’s persistent socio-economic problems, evidenced in failed efforts to wrest their nations out of the underdevelopment quagmire that has constrained their postcolonial progress and growth. The problems afflicting the region are a direct legacy of slavery. They are a consequence of the economic, political, social and cultural inequities created by the colonial powers in their drive to extract profits from their colonies.

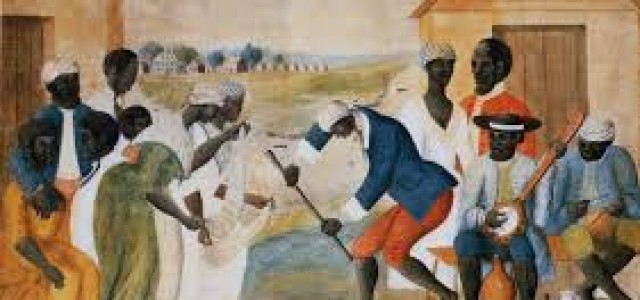

Caribbean intellectuals including CLR James, Eric Williams and Walter Rodney exposed the extent to which Europe’s economic development and current prosperity were predicated on centuries of exploitation of human and natural resources of Africa and the Caribbean. Slavery enabled traders, planters and merchants to accumulate fortunes through the systematic exploitation of millions of enslaved African men, women and children. Slaves toiled for long hours under horrific conditions to produce goods – sugar, cotton, tobacco – destined for European markets.

In Britain slavery facilitated the expansion of the major ports and industrial cities. Slavery ‘fertilised’ the rapid growth of the infrastructure that supported slavery: shipbuilding, iron foundries, rope making and the manufacture of armaments. Williams argued that the huge revenues generated from these industries provided the capital for economic development, spearheading the industrial revolution, and stimulating British capitalism. And British people at all levels of society consumed a growing market of luxuries hitherto enjoyed only by the wealthy and privileged as the plantations supplied the metropole with sugar, tobacco, coffee, rum, chocolate, fruits and the cotton that turned Manchester into ‘Cottonopolis’. In short, there was hardly a corner of Britain that did not in some way benefit from colonial slavery.

Back in the Caribbean the plantocracy enjoyed lavish lifestyles funded by profits from enslaved labour, but balked at reinvesting their profits to create the infrastructure needed to sustain the region’s long-term economic development. For the most part they pursued a mono-crop export policy linked to a dependence on imported goods from the mother country as mercantilist legislation prohibited the development of local manufacturing – ‘Not a single nail should be made in the colonies’ – as well as trade with other colonial powers. Mercantilism ensured the maximum extraction of value from the region and massive wealth accumulation in the mother country. The result was the region’s almost complete dependence on overseas markets – largely British – for machinery, food, household goods.

The planters established only the most rudimentary schools, health care and transport systems. Governmental institutions existed solely to maintain slavery and defend from foreign invasion and internal rebellion. When Caribbean nations embarked on the road to independence and nation-building in the 1960s, they did so shackled by undeveloped technological and scientific ‘capacities and infrastructure, hindering their ability to compete with more developed nations within the wider postmodern global economies.’

Moreover, slavery fostered divisive hierarchical social systems predicated on race and class and wide structural inequalities in the distribution of wealth and political power that persist today. As the plantation system evolved and African slavery became the cornerstone of the plantocracy’s labour policy, racialised discourses emerged promulgating the notion of black peoples as inferior, backward and uncivilised, and hence justifying the civilising influence of white European colonialism. Whiteness became associated with racial superiority, purity, wealth, privilege and freedom. These ideas initiated a link between whiteness and control of the world, its peoples and resources and assured the region’s whites social, political and economic dominance.

As today’s Pan-Africanists argue, the status quo remains largely unchanged in the 21st century. Even after abolition and emancipation, Europeans continued to extract profits from the region’s natural resources, while the majority of the formerly enslaved struggled to create sustainable family, community and social structures. Whites in the Caribbean are a minority, yet, supported by the structures that reproduced the race and class based inequities, they retain a firm grip on the post-colonial Caribbean economy and society. Many white families continue to live in sprawling plantation houses serviced and maintained by black domestic staff and funded by wealth accumulated during slavery and the post-emancipation era.

Against this backdrop, the Caribbean’s path towards development remains blocked. Beckles has identified a diverse array of factors that continue to impede progress in the region; this includes an education system that perpetuated colonial ideologies while doing little to prepare people for independent statehood. Around 70 percent of black people in British colonies were functionally illiterate in the 1960s. And one analyst has estimated that Caribbean governments allocate 70 per cent of national expenditure to education and health care.

The injustices perpetrated against humans should in themselves provide sufficient foundation for a moral case for reparations but it is the persistent systemic and structural deprivations that drive the current proposal. A case in point are on-going international trade agreements that lock the region into disadvantageous tariffs set by western economic markets and stifle economic growth.

I wrote this article in the same week that the Caribbean mourns the death of Professor Norman Girvan, one of its most eminent economists. Girvan had long been critical of the unequal terms of trade between the Caribbean and western economic blocs. In a 2011 lecture, Girvan drew attention to the almost total destruction of the region’s banana industry as a result of tariffs set by the World Trade Organisation. His predictions of the impact that the global economic crisis would have on the region are being borne out as local economies, already burdened by huge debt repayments, plunge further into fiscal deficit and dependence on the IMF.

Barbadians are currently struggling to survive harsh austerity measures that include wage freezes and lay-offs of thousands of public sector workers, as government attempts to impose structural adjustments to head off what the IMF described in February 2014 as ‘…headwinds that could result in a crisis’. The current austerity measures are set against a backdrop of rising national debt (94% of GDP in September 2013, up from 60% in 2009), low growth, a shrinking economy and a fixed exchange rate. Barbadians can take scant comfort from the knowledge that their fiscal challenges are shared by many of their neighbours. Western governments and supranational institutions maintain extraordinary power over the economies of the region in pursuit of their own geopolitical and economic ambitions. A case in point is the 2013 move by the US to force PriceSmart, one of its major corporations operating in the Caribbean, to suspend the accounts of Cubans living in Jamaica.

Baldwin Spencer, the Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda, outlined how the legacy of genocide, slavery, and colonialism strangled the region’s development arguing that “We know that our constant search and struggle for development resources is linked directly to the historical inability of our nations to accumulate wealth from the efforts of our peoples during slavery and colonialism”. For Spencer reparations represent a tangible, fair and just solution to the problems bedevilling regional developmental efforts. It is in this context that regional grass roots and civil society organisations, intellectuals, activists and professionals came together to craft a road-map for pursuing litigation.

That litigation will be difficult is in no doubt. Commentators point out that for the former colonial powers to issue formal apologies is to leave themselves vulnerable to claims for financial compensation. Also there are multiple practical problems. If the former colonial powers agree financial compensation, what form(s) should that assume? What sums can be put on human suffering? And which individuals should be compensated? Sexual relationships between slave-owners and the enslaved produced a situation where many Caribbean people are descended from both slave-owner and enslaved. How to even begin to untangle these genealogical knots? And who pays the bill? If it is European taxpayers, then will the burden not also fall on descendants of enslaved peoples now living in those countries? Should the wealthy descendants of slave-owners, those inheritors of huge country houses and estates and art collections be made to repay at least a proportion of their tainted inheritance?

CARICOM will also face an immense public hostility to the very notion of reparations. Without public support governments are unlikely to concede to demands for reparations, possibly arguing that to do so would be ‘undemocratic’. So hopes for full scale reparations are slim. But there are reasons to hope for some degree of restitution. In 2013, Leigh Day secured a US$21.5 million payment for hundreds of Kenyans beaten and sexually tortured by the British colonial government during the Mau- Mau Rebellion of the 1950s.

The legal case may fail, but the moral case is less easy to dismiss, especially when the nations of the former colonizers owe their present prosperity to the wealth accumulated from slavery. Recent research by University College London (UCL) has demonstrated the extent to which slavery underpinned the wealth of many contemporary Britons and institutions, including Barclays and Lloyds banks, and the Royal Bank of Scotland. Some of this wealth was accrued through investments in enterprises that supported slavery: shipping, iron and steel, insurance and banking.

Perhaps the most potent moral argument, and one CARICOM increasingly emphasizes, is that the British government paid an enormous amount of compensation to slave-owners for the loss of ‘their’ property. In the first reparations case in British history, in 1838 Parliament granted some £10m (an estimated £20 billion in current monetary value) to around 3,000 slave-owning families in the Caribbean and Africa, with another £10 million paid to absentee owners living in Britain, in restitution for the 655,780 human beings that they had enslaved, dehumanised, exploited and brutalised. What is striking is the spread of disbursements across all socio-economic groups. Small slaveholders, those owning less than ten slaves, were well represented among the recipients, and their numbers included some Black and coloured slaveholders.

Moreover, and most intriguingly, the records enable researchers to follow the money, and what is striking is the extent to which compensation payments were invested in industry, merchant banks, and marine insurance companies; in vast country estates and art collections. As the UCL Project Director Catherine Hall argues, the research demonstrates the indelible relationship between the ‘fruits’ of slavery, and the rise of modern Britain.

Also striking are the identities of the prominent beneficiaries of African slavery: Prime Minister David Cameron, former Tory minister Douglas Hogg, authors Graham Greene and George Orwell, poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Other prominent names include scions of one of the nation’s oldest banking families, the Barings, the second Earl of Harewood, Henry Lascelles, an ancestor of the Queen’s cousin, the new chairman of the Arts Council, Peter Bazalgette, and in a remarkable coincidence, 12 Years a Slave lead actor Benedict Cumberbatch, who has spoken candidly of his family’s role in slavery. Others, such as David Cameron, have been less forthcoming.

In stark contrast to the phenomenal sums received by the slave-owners, not a single enslaved man, woman or child received a penny in compensation for years of daily backbreaking toil that lasted from sun-up to sundown almost every single day of their lives.

Armed with these disclosures, CARICOM’s reparations committee proceeds in hopes that the legal obstacles to achieving justice can be countered with moral justifications resting on the injustice of awarding compensation to those who participated in and benefited from slavery while denying restitution to its victims.

Cecily Jones is a former Director of the Centre for Caribbean Studies at the University of Warwick and is currently an independent scholar. She is author of Engendering Whiteness: White Women and Colonialism in Barbados and North Carolina, 1627-1865.