Jackie Turton, Essex University

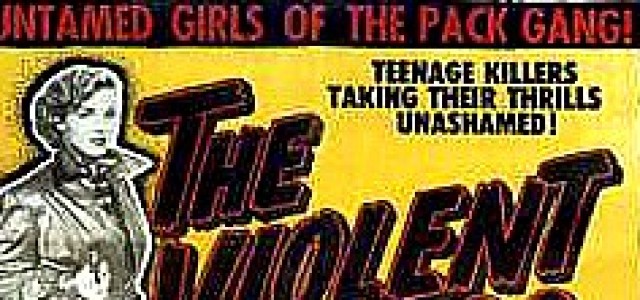

History reveals that moral panics (Cohen, 2011) about hooligans, gangs and uncontrolled youth, focussed attention on young people and crime long before the invention of the teenager. This has not changed. But while we continue to create folk devils of our children and young people, seeing them as a threat to the moral fabric of civilised society, we are also consumed with protecting their innocence. Thus we produce an on-going catalogue of moral panics depicting youth as dangerous or youth in danger.

It is interesting that despite the dramatic drop in recorded crime overall, concerns about the delinquency of young people remains high, indicating that as a society we do not rely on regular statistical updates for our knowledge of crime. In short, stories of crime are fuelled by media representations of feral children, out of control teenage gangs and street violence. The everyday notion of crime and deviance – mainly theft and bullying – and the everyday reality of victims – mainly the young people themselves – gets lost in the desire to produce and consume titillating, horrific and atypical crime events. The result is a demand for more social controls of the young and more punitive punishments.

With equal vigour the media pursue tales of victimhood, especially tales of physical and sexual abuse of the young, raising anxiety about the dangers of lurking paedophiles on street corners and, more recently, in internet chat rooms. The more likely scenario is that children and young people will be victims within their own home environment or at least at the hands of a known assailant. So, we have a situation where the knowledge base of youth deviance and crime, and victimhood, is often based on media constructions encouraging a dichotomy of moral panics. This victim – villain dualism muddies the water when we attempt to understand deviant behaviour.

What do we know?

Many of the traditional sociological ideas about youth crime have viewed the behaviour through the investigation of gangs of boys resulting in causal theories about problems of social disorganisation, disconnection with society, as well as an inability to adapt to dominant social norms. Some ideas have linked displays of delinquency by youth groups to the notions of resistance and strain, forcing young men to choose a delinquent pathway to ‘success’.

More recently we have recognised the excitement and thrill experienced by perpetrators of crime; the buzz of emotion set off by the risk-taking activity.

For young people who have the means, high risk and high cost activities such as exploring, mountaineering and motor racing are paraded as accolades and achievements, leaving the ‘street’ boys’ to gain respect through joyriding, violence and drugs. In fact concepts of risk have not been confined to explanations of deviant behaviour. Control of crime has moved into an actuarial approach not only assessing the risk of known deviants but also spreading the net wider in an attempt to predict and prevent crime. This system scoops up children from a variety of ‘at risk’ backgrounds. But it is in danger of over-predicting possible criminal activity and cites situations such as family breakdown, drug use, social exclusion, victimhood and gender as factors that should be taken into account when considering preventative tactics – indicated by the Youth Justice Board’s report in 2005 on Risk and Protective Factors. Despite some useful criticism, observing patterns of offences alongside predictive factors does offer interesting reading. It gives us the opportunity to reflect on our poor record of dealing with political and social concerns like poverty, inequality and class as well as how we might consider prevention through protective factors.

In terms of black youth there has been some notable and ground-breaking work in understanding the significance of, and links between, moral panics, discrimination and street crime (Hall et.al. 1978). It was not just the Stephen Lawrence murder that further highlighted the problem for black and Afro-Caribbean men, research shows that the stop and search regime used by the police to control the streets is far more likely to affect black and now Asian young men who have become familiar folk devils especially in the capital. The scene is slightly different, but no less significant in Scotland. Recent research shows that there young white, working class boys are four times more likely to be stopped than any of the groups living in London, including Asian and black youth, raising serious questions about how we treat all of our children and young people.

Girls alongside other female criminals have been viewed as mad rather than bad, a view that lingers in some of the literature and in parts of the criminal justice system. The gender assumptions in early research have been explored by a number of feminist researchers revealing an enclosed ‘bedroom’ girl culture (McRobbie 1978) as well as exploring the policing, regulation and victimisation of girls (Chesney-Lind & Pasko 2013). However, overall much of literature takes as its core data qualitative encounters with white, working class young men. Therefore at the moment it appears we have a situation where youth crime equals young, male, street crime and is highly visible. We have limited data that considers ethnic and gender issues – so where are the girls?

Where are the girls?

Over the last few years there has been a small rise in the reported crime figures for girls. Alongside this recent media reports indicate the familiar dichotomous problems raising concerns about the deviant behaviour and the lack of protection for girls and young women. The stories highlight the moral panics about girls especially concerning their violent behaviour and sexual vulnerability. Dramatic media images and text raise anxiety. Furthermore, the recent report for the Children’s Commissioner (2011) identified the roles that girls adopt in street gangs describing their violent and sexual behaviour which fuels these concerns.

The question to ask is whether this data is indicative of a modern female crime wave? All the evidence suggests that although many of the key predictive risk factors are the same for both, girls commit far less recorded crime than boys and the crimes that they do commit are less serious. Furthermore girls tend to engage with deviant behaviour later than boys and end their offending careers earlier, and overall they have a lower risk of reoffending. (Gelsthorpe & Sharpe, 2006) Boys are far more likely than girls to be arrested for both violent offences and theft. (Youth Justice Board, 2011/12)

So’ given these facts, any moral panics about the moderate increases in female crime seems disproportionate. Rather than a dramatic change in the actions of girls, the recent rate rise could be due to two important socio-cultural factors. Firstly, girls are spending more leisure time outside ‘on the streets’ away from the home, so they are more visible and accessible to a broader informal and formal surveillance system. Secondly, rather than an actual increase in crime, there has been a more punitive approach in the treatment of deviant girls.

The social notion of ‘bad’ girls may be further exacerbated by the concept that girls are ‘different’. They are controlled by the family and society in a way that has always been highly gendered, which is focussed on their femininity, sexuality and gender roles. Whereas the delinquent behaviour of boys maybe normalised as ‘just lads being lads’, the delinquent behaviour of girls is linked to perceptions of appropriate female behaviour. In other words, female delinquent behaviour does not just lead to punishment of the deed but also to condemnation concerning social expectations of the feminine role. Thus, we create a ‘double deviant’ (Lloyd, 1995) response that deepens our concerns about the behaviour of girls and young women.

The second moral panic that media stories may provoke is one about victimisation, youth in danger. The question therefore might be are girls at more risk of becoming victims? Criminalisation and victimisation are closely linked. Not only is victimhood a risk factor in predicting criminal activity for girls, the criminal activity itself can lead to vulnerability, as suggested above. Furthermore, straying from the expected role model can leave girls vulnerable since a ‘bad’ girl maybe perceived as less of a victim.

The recent Jimmy Savile scandal indicated how he did not just rely on his powerful situation, but invariably chose vulnerable victims. In some cases the young girls he chose were already in care and therefore less likely to be believed indicating the punitive approach to ‘bad’ girls. There are similarities with the victims of the Rochdale and Birmingham trafficking cases where again rather than being recognised as victims, the girls were assumed to be making choices about their sexual behaviour.

Conclusion

Concerns over youth crime are not new. The behaviour of young people over generations has provoked outrage about moral decline and lack of regulation. Moral panics have flared and died and new ones take their place. Despite the overall fall in crime rates, the response to high profile cases in recent years has lead us to a more punitive approach to youth crime and moved us away from understanding their victimhood. This action disproportionately affects ‘bad’ girls – as they are more likely to be victims as well as ‘villains’.

References:

Chesney-Lind M & Pasko L. (eds.) 2013, The female offender: girls, women and crime, Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Cohen S. 2011, Folk devils and moral panics: the creation of the mods and rockers, London: Routledge

Gelsthorpe L & Morris A. (eds.) 1990, Feminist perspectives in criminology, Milton Keynes: Open University Press

Gelsthorpe L & Sharpe G 006 Gender, youth crime and justice, in Goldson B & Muncie J, Youth crime and justice, London: Sage

Hall S, Critcher C, Jefferson T, Clarke J & Roberts B. (1978) Policing the crisis: mugging, the state and law and order, London: Routledge

Hier S, Lett D, Walby K & Smith A 2011, Beyond folk devil resistance: linking moral panic and moral regulation, Criminology & Criminal Justice, 11:3:259-276

Lloyd A. 1995, Doubly deviant, doubly damned: society’s treatment of violent women, London: Penguin Books

McRobbie A, 1978, Working class girls and the culture of femininity, in Centre for Contemporary Studies, Women Take Issue, London, Hutchinson.

Jackie Turton is senior lecturer in sociology at Essex University. She has worked as an associate lecturer for the Open University in the Faculty of Health and Social Welfare and been teaching sociology and criminology since 1996. Jackie is an experienced qualitative researcher and has completed projects for both the Home Office and Department of Health.