Paula Reisdorf

Over the past decade, large swathes of land in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have been grabbed by European multinational companies, governments or private individuals. The same land that was used to grow food for domestic consumption is now growing biofuel crops – like jatropha or palm oil – that are exported to the European Union (EU). What does this remind us of? India in the 19th century? How did we arrive at this neo-colonialist scenario? In order to answer that question, we need to look at a change in the EU’s environmental policy that occurred in 2009.

In 2009, the EU passed an agreement, known as the Renewable Energy Directive (RED), in which it set out its commitments for the next decade. One of the chapters of this agreement required all member states to ensure that 10% of their transport fuel comes from biofuels by 2020.

The European Union has been relatively successful in implementing this agreement, as the percentage of its transportation energy coming from biofuels has more than doubled. In 2008, only 3.3% of its transportation energy came from biofuels but by 2019, this number had reached 7.3%. However, most of this biofuel isn’t grown in Europe. According to the EU’s own data, more than half of it is imported with much of it coming from SSA.

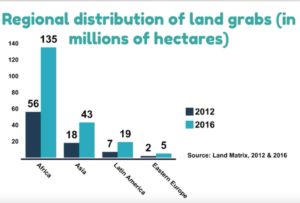

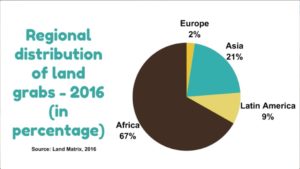

Between 2012 and 2016 the African continent was the main target of large-scale commercial land deals, with 135 million hectares leased in 2016 alone, more than the rest of the world combined. Of the total global land deals in 2016, two thirds occurred in Africa. What is, in essence, happening, is that European multinational companies, governments or private individuals are buying up African land to grow biofuel crops.

The World Bank argues that large-scale commercial land deals strengthen food security by improving technology, innovation and productivity. The reality on the ground, however, paints a very different picture. Rather than growing maize, cassava, wheat or other staple foods with improved technology, farmers are now primarily growing biofuel crops to be exported to Europe.

Of the land involved in large-scale land deals in Africa in 2012, 66% was used to grow biofuel crops and only 21% was used to grow food. 19 of the 29 million hectares that were involved in land deals were linked to biofuels. This puts in question the food security argument, as smallholder farmers who were growing food were often displaced after the land was sold to investors.

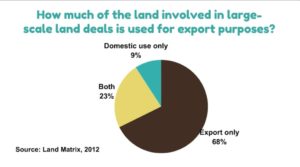

Not only is the land now used to produce biofuels, but most of what is grown is actually exported. To be exact, 68% of global land grabs occurring in 2012 involved land that was geared towards exports. In the same year, only 9% of the land involved in these deals was geared towards domestic use. “What is effectively happening is that large areas of land are being diverted from growing food for the poor to growing fuel for the rich”, says the Ghanaian scholar Dr. Ernest Nkansah-Dwamena.

Since communities rarely give their consent when these large-scale commercial land deals happen, some scholars prefer to use the term “land grabbing” to describe them. Keamogetswe Seipato, the coordinator of the Southern Africa Campaign to Dismantle Corporate Power, defines land grabbing as “the unlawful seizure of land without people’s consent”.

European actors – both public and private – are grabbing land in Africa to meet Europe’s energy needs. They are effectively removing African citizen’s own sovereignty over their land and depriving them of access to food. There are few examples that meet the definition of neo-colonialism so perfectly. Neo-colonialism is the use of political, economic and military methods to control a country. In most cases, it involves a former colonial power – in the Western world – controlling a formerly colonized country – in Asia, Latin America or Africa. According to Kwame Nkrumah, the father of the theory of neo-colonialism, “the result of neo-colonialism is that foreign capital is used for the exploitation rather than for the development of the less developed parts of the world.” It is clear that the EU’s biofuel-driven land grabbing is not happening for the development of sub-Saharan Africa, but rather for its exploitation in order to meet the EU’s energy needs.

What has been the consequence of this neo-colonialism led by European institutions? FAO data shows that Africa is the only continent in which food security has worsened since 2010 – with the percentage of those undernourished out of the total population increasing from 18.3% to 20%. This is in contrast to Asia and Latin America where the percentage has been steadily decreasing. Nkrumah envisioned that this would be the consequence of neo-colonialism, as “investment, under neo-colonialism, increases, rather than decreases, the gap between the rich and the poor countries of the world.”

One of the major tools of resistance against this land grabbing has been the concept called Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). This concept holds that indigenous people must be informed about a potential development on their land in a way that is free from intimidation, prior to the development itself and contains the full information. Furthermore, rather than just being consulted, they should then be allowed to either consent or oppose the development. FPIC is increasingly being pushed on the agenda of multilateral organizations like the United Nations (UN) while and some countries like Peru, Australia and the Philippines have even recently included FPIC in their national laws.

While FPIC is a step in the right direction, it is still in its beginning stage of being acknowledged by corporate and government actors in the land grabbing sector. Hopefully, the local and global struggles will be strong enough to finally achieve people’s sovereignty over their own land.

Paula Reisdorf is the founder of Sankara Media, a recently established independent media organization focusing on social justice and decoloniality.