Laurence Cox

In the midst of the virus, locked away in separate houses, our computer screens are filled with visions of a better world. Our inboxes and social media feeds are bombarded with stories about how the virus shows us that another world is possible, what we must learn from the crisis, why we cannot go back to how things were, what the virus means for the future, how the world will change.

Some are written in the language of normative political theory and social policy, or what sociologists technically call “wishful thinking”: talking about what “we” want, without asking how we are going to get it. Others are framed as objective statements about how this or that change must happen, why there is only one possible road forwards. If only it was that easy.

As social movement scholars have long observed, there is no way around the question of agency. What happens after the virus will not be determined by what is good or what we believe to be true, but by the organisation of people around interests and ideas, for good or ill. And it is voices from the UK and USA, where social movements are weak and the Trump and Johnson projects are strong, that most carefully avoid asking “what are we going to do to bring this better world about?” in favour of mapping its continents or discussing the geological processes that will inevitably produce it.

We have been here before: nearly a century ago, Gramsci noted that fatalistic visions of inevitable progress are attractive in periods of defeat, while coherent discussion of actual strategy belongs to the moment of possibility.

But there is another wrinkle to these policy programmes for fantasy governments: even when movements and communities in struggle have the power to overthrow an existing order and remake it from scratch, what happens is rarely what was envisaged. The history of revolutions, those moments when society transforms the state and remakes the world, underlines that popular ideas normally change radically as people “transform themselves and things”. The outcomes are other than what was imagined – in democratic welfare states and independent nation states as much as in “actually-existing socialism”.

Part of the fantasy is this idea of a pre-existing programme, policy, vision that somehow doesn’t alter as tens of millions of people change the wider context of their own lives, and as those changes – to the economy and the state, everyday life and popular culture, media and religion – take shape. This is a deeply managerial fantasy, in which somehow “everything changes” but the basics – a small group of people implementing a “new direction” from on high – doesn’t. Sometimes, of course, such visions can stay the same because it doesn’t actually matter – it is only the advertising slogan for the new boss, same as the old boss. But what is the actual relationship between visions of change and real social change?

The lost futures of Asian decolonization

On any serious account, the largest social change from below of the last century is decolonisation in Asia (where about 60% of our species lives) and Africa. Globes and atlases began the twentieth century dominated by a handful of colours, marking the British, French and other European empires. By the end of the twentieth century, they showed a proliferation of independent nation-states. This was an extraordinarily dramatic process, driven by a wide range of popular movements and alternative elites and with a whole spectrum of political colourings – whose unfinished business reverberates to this day.

Yet in 1900, it was far from obvious that the world after Empire would take this shape; after all, most of imperial Europe was itself dominated by dynastic monarchies. At the end of WWI, revolutions and crisis saw most of Ireland leave the “United Kingdom”; while the Romanovs, Hohenzollerns, Hapsburgs and Ottomans saw their empires collapse, and the nation-state started to seem like the wave of the future.

As Pankaj Mishra and Douglas Ober have shown, the scale of the challenge of imagining change in Asia was an enormous one, even for the finest minds. Nostalgia for restoring past kingdoms jostled with visions of a future shaped by reason, science, technology, education and law. The anarchist possibility of a stateless society was increasingly displaced after 1917 by communism, which not only offered the promise of a non-capitalist modernity but crucially offered a rational strategy for how to get there. Religion, too, offered a possible future: pan-Islamic thought could not only reach back to the caliphates but forward into a world that empire had connected through the telegraph, the steamship, the printing press and the railway.

In other words, the production of visions of a better future is a sign of the difficulty of really imagining social change on such a deep and wide scale. However much it adopts the rhetoric of rational policy-making, objective social analysis, moral philosophy or economic necessity, today’s version is as utopian as the millenarian visions of peasant uprisings, equally incapable of imagining the process of change or the nature of the agency that it requires. Like millenarianism, it tries to construct agency behind its authors’ own backs, invoking determinism or moral necessity to conjure up the action that would actually be needed to bring its imagined Pure Land into being.

The pan-Asian Buddhist revival

With Burma specialist Alicia Turner and Japanologist Brian Bocking, I’ve just published The Irish Buddhist: the Forgotten Monk who Faced Down the British Empire with Oxford. It traces the story of Laurence Carroll / U Dhammaloka, an Irish emigrant, hobo and sailor who became a Buddhist monk in Rangoon in 1900 and a leading anti-colonial activist across Asia. Active in today’s Burma, Japan, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, India, Bangladesh and maybe Cambodia, Nepal and China, Dhammaloka had at least 5 aliases, 25 missing years in his biography, was under police and intelligence surveillance, tried for sedition, faked his own death and eventually disappeared.

We use this extraordinary life as a window into the subaltern worlds of the pan-Asian Buddhist revival, the process whereby Buddhism became a global world religion, cast in rational terms and ultimately centred around the “mental science” of meditation. This is sometimes studied as “Buddhist modernism”, the construction of new discourses about the rational meaning of Buddhism and its adoption by educated, urban Asian laity as a political organising tool in nation-state formation.

Yet – within empire – Buddhism was pan-Asian. Sri Lankan activist Anagarika Dharmapala, for example, could cast Bodh Gaya as a new Jerusalem for an imagined community “from the banks of the Caspian Sea to the distant islands of Japan, from the snowy regions of Siberia to the Southern limits of the Indian Ocean”. Buddhism was known to be older than Christianity and (wrongly) believed to have more adherents – as well as a historical source in India. Against the militarism and racial hierarchies of Empire, it could be understood as radically egalitarian and pacifist.

And it enabled new kinds of networking. Less important in some ways than U Dhammaloka as European, English-speaking “front man” are the Asian organisations and networks who found him useful: ethnic minority Buddhists in Burma and Thailand, Indian nationalists and Sri Lankan radicals, Chinese philanthropists and Japanese modernisers. Behind these again lie the “plebeian cosmopolitanisms” of port towns like Rangoon and Penang, Singapore and Bangkok, with their many different ethnic communities of migrant labourers, “poor whites” and sailing or trading diasporas.

When Dhammaloka was tried for sedition in Rangoon in 1911, the Burmese, Chinese and Indian (mostly Muslim) bazaars shut down in support; the cinema and an Indian National Congress paper defended him. It is these urban realities and Asian networks that gave power to his repeated critique of colonialism as bringing “the Bible, the whiskey bottle and the Gatling gun” (missionary Christianity, cultural destruction and military conquest) and the action that followed.

Like EP Thompson’s or Christopher Hill’s radicals, Dhammaloka’s multi-ethnic organising was another “lost future”, ultimately displaced by successful nationalists – but as Subaltern Studies has long shown, if we want to understand how large-scale social change on this scale comes about, we need to pay attention to the multiplicity of contending popular movements, in all their apparent strangeness, and not simply the programmes of the eventual statemakers.

“… the point is to change it”

Pace Zizek, it proves all too easy to imagine the end of capitalism: my inbox is full of it. What is hard is to organise the necessary popular agency, the social movements capable of preventing the end of the world and constructing a better one. The worlds I have described are complex and different to our own, but if we are serious about change we need to move away from writing policies for the civil servants of the future in our own voice, and try harder to listen to the voices of those who were actively engaged in movements that ultimately helped bring about real, large-scale change.

Laurence Cox (@ceesa_ma) is an experienced activist and social movements researcher, Associate Professor in Sociology at the National University of Ireland Maynooth and founding co-editor of Interface. The Irish Buddhist (Oxford 2020) is available in ebook here; hardcopies can be ordered here at a 30% discount using code AAFLYG6 (shipping once warehouses reopen).

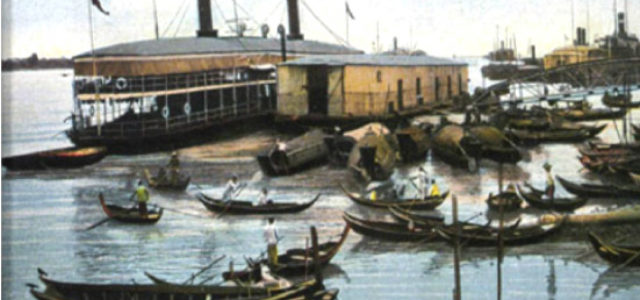

Image Credit: Rangoon Harbour, 1885 from a postcard of the period. Uploaded to Wikimedia Commons by the Myanmar Port Authority