Achala Gupta and Katie Chadd

Amidst the rapidly growing impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, many hidden realities of our everyday lives have become apparent. Situated in the Corona-era, this piece focuses on the sequential processes of understanding, adjusting and coping with the ongoing pandemic from a differently-abled perspective. In doing so, we examine the everyday social management of a pandemic and show how this public health emergency has surfaced, accommodated, and at times caused further marginalisation of socio-historically disadvantaged groups that tend to struggle to find their place in ‘abled’ society. We consider the Covid-19 pandemic as a transition to a more inclusive society in the newly found spirit of collective action and shared responsibility.

Understanding

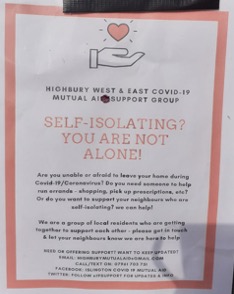

The fast spread of Covid-19 worldwide has resulted in mass adoption of new vocabularies and concepts. A clear understanding of concepts, such as ‘social distancing’, ‘self-isolation’, and ’pandemic’ along with knowing about personal health, the nature of transmission of infectious diseases, and maintaining hygiene has become a civic duty. While our repertoire of terminology has increased, some of the mass-adopted responses haven’t been particularly rational, primarily due to the lack of understanding of the situation in its entirety. Although keeping up with swiftly changing government instructions and responding to them appropriately has been challenging for many, this unprecedented ‘new normal’ is particularly difficult for populations who face barriers to understanding.

The fast spread of Covid-19 worldwide has resulted in mass adoption of new vocabularies and concepts. A clear understanding of concepts, such as ‘social distancing’, ‘self-isolation’, and ’pandemic’ along with knowing about personal health, the nature of transmission of infectious diseases, and maintaining hygiene has become a civic duty. While our repertoire of terminology has increased, some of the mass-adopted responses haven’t been particularly rational, primarily due to the lack of understanding of the situation in its entirety. Although keeping up with swiftly changing government instructions and responding to them appropriately has been challenging for many, this unprecedented ‘new normal’ is particularly difficult for populations who face barriers to understanding.

The linguistic and communicative complexity of the Covid-19 pandemic may predispose some groups to a deficit in understanding as well as acting on knowledge. For example, someone with developmental language disorder (DLD) requires repeated, explicit instruction of vocabulary (Wright, Pring & Ebbels, 2017) to fully grasp the meaning of words. While the general population is expected to absorb the meaning of new concepts from the media, this mechanism is insufficient for people with DLD. Furthermore, the general public struggles to filter out the misinformation and myths about Covid-19. Making accurate judgements amidst this ‘infodemic’ requires tools, including a sophisticated understanding of what makes a reliable source and sound critical reasoning skills, which are likely to be impaired in people with language and communication disorders (Baldo et al., 2015). The disparity in grasping new social norms may potentially pose hurdles to the accessibility to the information and comply with the recommendations for managing the Covid-19 pandemic for individuals with language or communication disorder, learning difficulties, and neurodivergencies such as autism, dyslexia or chronic mental health disorders.

Adjusting

Social norms that curate the mundane, and guide everyday behaviour, change – often gradually – over time. In a pandemic situation, the social code of conduct is suddenly revised to address the public health crisis. It is becoming ‘normal’ to keep a 2-meter distance with one another, and fulfil the 20-second hand-washing rule. These quickly learned behaviours are adopted in response to the public health emergency and were previously not a part of our everyday life. Moreover, while adapting to the rapidly changing guidance for the public, we are swiftly and proactively changing our ways of being.

The processes of adjustment for the general population also comes with greater empathy, and therefore, understanding of others living in different circumstances. Isolation and limited autonomy over one’s actions now being enforced upon most people is an everyday experience for many differently-abled individuals. Whilst the public adjusts to being turned away from their favourite places due to Covid-19 closures, wheelchair-users are often excluded from venues serving even the most basic of their needs. Similarly, while professionals adjust to the ‘novelty’ of working from home, for some with disabilities, this has been the only reasonable option for a professional career.

The processes of adjustment for the general population also comes with greater empathy, and therefore, understanding of others living in different circumstances. Isolation and limited autonomy over one’s actions now being enforced upon most people is an everyday experience for many differently-abled individuals. Whilst the public adjusts to being turned away from their favourite places due to Covid-19 closures, wheelchair-users are often excluded from venues serving even the most basic of their needs. Similarly, while professionals adjust to the ‘novelty’ of working from home, for some with disabilities, this has been the only reasonable option for a professional career.

Interestingly, proactive, sensitive and accommodating routines have demonstrated how services can actually become accessible. In some cases, priority for accessing goods and services have been offered to those with disabilities, for example, protecting time for ‘vulnerable’ people to do their grocery shopping. There may even be extended benefits to these novel ‘norms’. For instance, those who find it challenging to get out of the house can secure video-consultations with their General Practitioners much more easily, and people who are immunocompromised may be benefited by the ‘newly learned’ personal hygiene regimes we must employ.

Stories continue to emerge about specific challenges in adjustment that differently-abled people are experiencing in the face of Covid-19. For example, as the general population fear and subsequently avoid touching surfaces in the public domain, those who rely on tactile cues such as people with a visual impairment may be more restrictive in their tolerance for these adaptations. Similarly, the health practitioner with a hearing impairment who relies on lip-reading is suddenly isolated, as colleagues converse through face masks. Furthermore, in order to balance medical supply and demand arising from Covid-19, the emerging triage policies for interventions may directly discriminate against the differently-abled. For example, the chances of a Covid-19-positive individual with certain disabilities being fitted with a respirator or getting admitted to hospital may be lower than the typical patient.

Coping

As we struggle and cautiously succeed in understanding the situation and adjusting to it, we realise that the pandemic cannot be contained in our desired time and pace. With the recognition that the current situation cannot be tackled immediately, the general public has to resort to coping within the current circumstances. The uncertainty associated with the situation has caused excessive anxiety and fear among the general public, making it far more difficult to cope with the regularly updated reality. Many people have lost their anchor, their schedules, and are now operating in an unfamiliar infrastructure with substantially revised social norms.

As we struggle and cautiously succeed in understanding the situation and adjusting to it, we realise that the pandemic cannot be contained in our desired time and pace. With the recognition that the current situation cannot be tackled immediately, the general public has to resort to coping within the current circumstances. The uncertainty associated with the situation has caused excessive anxiety and fear among the general public, making it far more difficult to cope with the regularly updated reality. Many people have lost their anchor, their schedules, and are now operating in an unfamiliar infrastructure with substantially revised social norms.

Notably, many people are realising what it means to experience anxiety arising from situations and circumstances that they do not quite grasp and on which they have little control. This perceived chaos among the wider population is an everyday reality for the non-typical – more specifically, the non-neurotypical group. Many who identify as autistic or neurodivergent express a similar intensity of anxiety regularly in their everyday contexts (Hollocks, Lerh, Magiati, Meiser-Stedman & Brugha, 2019). Autistic people acquire strategies to manage intolerance of uncertainty, some of which may manifest in behaviours typically construed as ‘autistic’– a longing for adhering to a routine, rigidity in behaviour which reduces the likelihood of an unanticipated event, and avoidance of situations where an outcome is indeterminate (Boulter et al., 2013). Given the global uncertainty perpetuating from the pandemic and the subsequent inability to truly implement these strategies, it would be reasonable to expect that individuals in the neurodivergent community would be facing extreme levels of anxiety and will require substantially more support throughout this period than usual in order to cope with the impact of Covid-19. Various creative processes of coping that the general population have adopted during the pandemic in recent weeks will still be required for specific groups of people post-pandemic.

Final thoughts

We hope that this piece has shown, to some extent, that what the general public considers as a ‘new normal’ in the Covid-19 pandemic is often an everyday reality for people with disabilities. Furthermore, these already marginalised individuals are likely to understand and experience the pandemic fundamentally differently to the general population. While society bears witness to a collective dent in morale and wellbeing arising from the pandemic, it is pertinent to reflect on the amplified impact of the disruption on the differently-abled. Some policies being implemented with the aim to mitigate inequity of service to vulnerable groups may be considered successful at present, but it raises concerns around the sustainability of these measures. Will these benevolent pandemic-responsive policies that have been put in place to minimise the risk of fatalities of a vulnerable population translate into longer-term interventions to maximise their chances at obtaining equality in the post-Covid-19 world?

The society, as we know it, is currently undergoing an unprecedented change, ranging from local to global, personal to political, individual to infrastructural. We have begun to ponder over our fundamental ways of being. These contemplations are likely to shape the world of tomorrow, whenever that tomorrow may arrive. To ensure that the anticipated social changes are for the better, it is imperative to explore and engage with conversations that we think are crucial to our collective selves. Imagining the current pandemic as a gateway to a new world, we need to make attempts to know and pledge to change our ways of thinking, acting, and behaving in this transitional period to ensure that the ‘edited world’ that awaits us on the other side of the Covid-19 pandemic is more inclusive, understanding, and compassionate.

The society, as we know it, is currently undergoing an unprecedented change, ranging from local to global, personal to political, individual to infrastructural. We have begun to ponder over our fundamental ways of being. These contemplations are likely to shape the world of tomorrow, whenever that tomorrow may arrive. To ensure that the anticipated social changes are for the better, it is imperative to explore and engage with conversations that we think are crucial to our collective selves. Imagining the current pandemic as a gateway to a new world, we need to make attempts to know and pledge to change our ways of thinking, acting, and behaving in this transitional period to ensure that the ‘edited world’ that awaits us on the other side of the Covid-19 pandemic is more inclusive, understanding, and compassionate.

Achala Gupta is a Research Fellow in the Department of Education, Practice and Society at the UCL Institute of Education, University College London. Twitter: @achalagupta

Katie Chadd is a trained Speech and Language Therapist. She is a Research Officer at the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. Twitter: @Katie_Chadd

Image Credit: all images by Achala Gupta