Lisa Arai

The emergence of the novel coronavirus strain, Covid-19, has been understood primarily as a medical and public health phenomenon, but it is also a geographic one. Measures to suppress the virus have necessitated a near total inversion of people’s normal behaviours in geographic spaces: in the home, the community or further afield. On 25th March 2020, one third of all people in the world were in a state of ‘lockdown’ and (to varying degrees) confined to hospitals or medical settings, unable to work outside the home, engage with others in their communities, travel far without good cause and, in some cases, even mix with loved ones in their own homes.

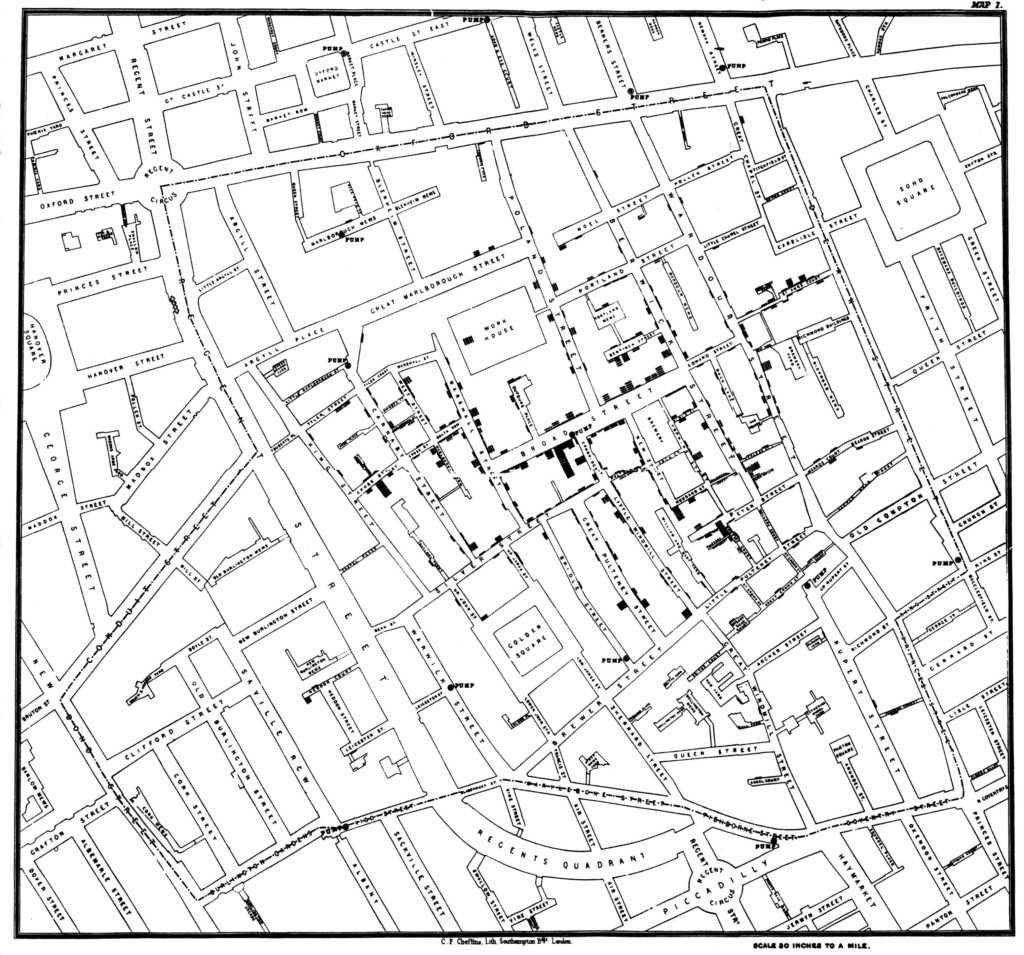

Geographic containment is a well-established strategy for managing contagion, and geographic analysis is a key tool for aiding containment. And it is one with a long history. The Italian plague suppression of 1694 involved the ‘earliest map visualisation of the relationship between place and health’. John Snow’s famous map of households affected by cholera in Soho in the mid-19th century is often cited as an example of epidemiological detective work.

Image Credit: Wikimedia

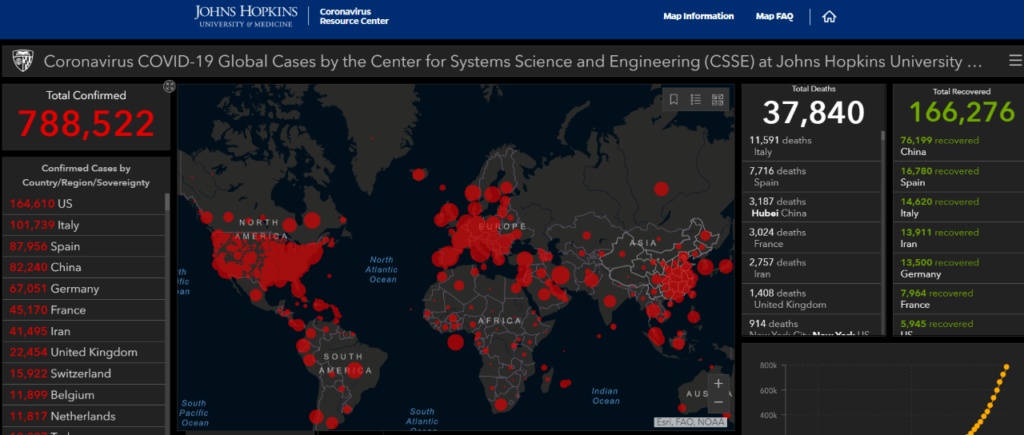

Our own understanding of the spread of Covid-19 is facilitated by sophisticated geographic imagery showing the global spread of cases, and spatial (as well as temporal) analyses of transmission infection underpin current public health strategies to ‘flatten the curve’.

Image Credit: Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering

Geographic analyses of viral outbreaks focus largely on the one dimensional, physical aspects of place: where infection is located and where it moves to (and how fast it moves there). Explorations of place and space have traditionally been the province of geographers, such as the late Doreen Massey who resisted the conceptualisation of space has having only physical dimensions and argued that place and space are about: ‘…our relations with each other … social space … is a product of our relations with each other, our connections with each other’. Conceiving of space this way, and moving beyond public health’s, macro-level focus on (physical) place, it’s clear that measures to contain the pandemic have radically transformed everyday geographies in visible and less visible ways.

In the personal spaces of the home, the practice of self-isolation involves extreme withdrawal from shared areas and extensive measures to avoid viral contamination of communal household surfaces. In the community, the most visible signs of the new geography are in supermarkets and banks. Formerly places where customers could move around relatively freely (certainly true of supermarkets, as evidenced by maps of ‘shopping paths’ showing consumers’ zig-zagging, convoluted browsing routes), these are now spaces characterised by barriers, hand-written warning signs and social distance exclusion zones (the latter hastily created using boldly coloured barrier tape and reminiscent of crime scene tape). The same social distancing techniques are in place outside shops, where queues of shoppers standing two metres apart are now commonplace.

This transformation is also reflected in our language; the inherently spatial concepts of ‘social distancing’ and ‘self-isolation’ – ideas previously confined largely to epidemiological journals – are now part of everyday language. Yet, only a few short weeks ago, most people would not have understood these terms and knew even less how to engage in these practices.

The new geographies are policed not only by state agents but also by others in the community. The violation of social distancing protocols, even inadvertently and in apparently minor ways, can incur the wrath of others. Breaking new rules about walking and exercising in public places (and which are at odds with mainstream health promotion messages about the benefits of exercise in green spaces) can result in ‘lockdown shaming’. Stories are emerging of competing groups (such as joggers and dog walkers) jostling for space and denouncing each other’s ‘inappropriate’ use of space. These developments point to the emergence of a new kind of spatial anxiety, one where previously mundane social interaction in public places is now regarded as potentially life-threatening.

To date, the evidence suggests these strategies appear to be effective in slowing down transmission of the virus. It’s possible that, had these preventative measures remained advisory only and without legal sanction, they may not have been as well observed. Maybe this radical curtailment of people’s movements (and which does not, as yet, have an apparent end) is a price worth paying.

There is, however, a good chance we will not ‘get back to normal’ as our politicians have promised once the pandemic ends. Covid-19 has been cited as an example of what Harold Garfinkel described as a ‘breaching experiment’ in his 1967 Studies in Ethnomethodology: an event where disruption to the familiar, taken-for-granted world renders the norms governing social behaviour and interaction visible. Garfinkel conducted notorious experiments to demonstrate how social order is constructed and maintained and, importantly, how the breach is resolved and ‘normal’ social order reasserted. Our post Covid-19 social order may be very different to our pre-Covid 19 social order. For one, will we mix freely with others once suppression measures have been lifted? Or will we continue to adopt the same spatially anxious strategies in preparation for the next pandemic?

The pandemic’s transformative potential is enormous. It is even seen by some as an opportunity for a social, economic and political ‘reset’. One high profile commentator has argued that Covid-19 offers a ‘blank page for a new beginning’. Understanding the societal ruptures engendered by the pandemic – especially the altered geographies of the everyday world – is deserving of in-depth examination. Whatever the future holds, the Covid-19 pandemic offers ample opportunities for social scientific insight and analysis.

Lisa Arai is a Senior Lecturer in Health and Social Care at Solent University, Southampton.

Image Credit: Tamsin Arai Drake