Elisa Pieri

The current outbreak of COVID-19 is a stark reminder of our permanent exposure to risk of pandemic outbreaks. To prepare and respond more effectively to pandemics we need to put in place mechanisms for decision making that are procedurally fair, inclusive of all relevant knowledge (notably, sociological and social science knowledge, alongside medical knowledge and other logistic and command-and-control expertise) and involve an all-of-society approach. Understanding and studying societal and ethical impacts of pandemic preparedness and response are key contributors to achieving better and more socially robust mitigation. Pandemic measures have unequal impacts on different groups of people, and different groups of people need to be involved in debating (ahead of an outbreak) and co-shaping the mitigation strategies to be deployed. During a pandemic, mechanisms for looping back the experience and impacts that various measures (such as quarantine/lockdowns) have on different groups of citizens need to be deployed.

Novel infections that have the potential to be of high-consequence are always emerging. It is estimated that since the mid-1970s, at least 20 entirely novel and lethal infectious diseases have been identified, including Ebola [1]. Others that were already known to us, and against which we had developed effective pharmaceutical responses, are re-emerging in variants more virulent and resistant to our drugs, as the surge in cases of multi-drug-resistant Tuberculosis shows.

Under the aegis of the World Health Organisation, the international community and national governments are steadily seeking to respond by containing and mitigating the impact COVID-19 infection. The number of confirmed cases worldwide has now exceeded 200,000 and is rapidly accelerating. As the WHO reports, it took three months to reach the first 100,000 confirmed cases, and only 12 days to reach the next 100, 000. As of 16th March 2020 ‘the total number of cases and deaths outside China has overtaken the total number of cases in China’, with more than 80% of all cases being from two regions – the Western Pacific and Europe, and fatalities currently approaching 9,000 globally (as of 20th March 2020).

Enormous progress has been made in responding to public health emergencies of communicable disease and in coordinating action internationally. China needs to be commended for the formidable rapidity in isolating and sequencing the virus, and even more so for promptly sharing with the international community this and other key information. The move has been pivotal in allowing other countries to rapidly detect and isolate imported cases of the disease. It helps all countries to develop diagnostics and collaborate in researching the novel coronavirus, and to develop effective interventions in response to it.

Yet, more needs to be done to understand the social repercussions that the measures taken have on citizens and their welfare. Even in the midst of intense response and coordinated international scientific efforts, there is no time like the present to focus on a key aspect of pandemic preparedness, and one that too often is overlooked – the social (non-medical) impacts on citizens’ of the measures implemented. Infectious disease outbreak mitigation greatly benefits from the input of collaborations across countries and disciplines. It is time for such collaborations to also extend to social scientists, to help develop better, more equitable, measures that address the impacts (medical and otherwise) of pandemic response on those affected.

Sociological knowledge and expertise must not be confined to interventions around best communication strategies. Instead, sociological expertise is key to tackling stigma and highlighting how measures have had very differential effects on citizens and on different demographics amongst the population targeted, as evidenced in the management of past outbreaks, including SARS and MeRS [2]. Despite widely circulated international guidelines, countries adopt different measures [3], as it is entirely their prerogative to do (see also). These measures, as research shows us, have often created inequalities, as well as exacerbating existing social inequalities that were already experienced in pre-pandemic times [4].

The novel COVID-19 coronavirus is not fully understood. Amongst the initial unknowns were also its pathways of communicability. As knowledge accumulated, we now know that good public health containment efforts to seek to break or limit human-to-human transmission via testing, isolating those infected, tracing their contacts and quarantining them, are very effective, and need to be pursued alongside mitigation strategies to reduce social contact. Even as a new evidence base is forming, many unknowns remain, and others are systemic – including, unknowns about whether or when the virus, currently remarkably stable, will mutate, or whether it may come back again, after we extinguish the current outbreak. In these conditions of radical uncertainty and in the climate of commendable transparency and data sharing for more effective coordinated response, it is imperative that we also learn of the impacts that the measures implemented are having on citizens across the globe. We must look at where the greatest difficulties and inequalities are, put in place solutions to overcome these and help the most vulnerable.

A sustained and inclusive public debate needs to occur in pre-pandemic periods. During an outbreak, like the one we are facing now, mechanisms for feeding in the experiences and difficulties encountered by various groups of citizens must be put in place to achieve a better and more socially robust pandemic response. Greater collaboration across disciplines, greater public engagement and a whole-of-society approach need to be fostered.

Notes:

[1] Abraham, T. (2007). Twenty-First Century Plague. The Story of SARS. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

[2] Jacobs, L. (2007). Rights and quarantine during the SARS global health crisis: Differentiated legal consciousness in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Toronto. Law & Society Review, 41(3), 511-756; Teo, P., Yeoh, B. & Ong, S. (2005). SARS in Singapore: surveillance strategies in a globalising city. Health Policy, 72, 279-291; Lai, A. & Tan, S. (2013). Impact of Disasters and Disaster Risk Management in Singapore: A Case Study of Singapore’s Experience in Fighting the SARS Epidemic. ERIA Discussion Paper Series. ERIA-DP-2013-14. Singapore: Ministry of Home Affairs; ASSET (2016). Democracy and human rights under Public Health Emergency (PHE) threat. ASSET Paper Series. Rome: Zadig. See also here and here

[3] ECDC (2017). Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans: Lessons learned from the 2009 A(H1n1) pandemic. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; WHO (2016). Progress report on the development of the WHO Health Emergencies Programme. Geneva: WHO; Jacobs, L. (2007). Rights and quarantine during the SARS global health crisis: Differentiated legal consciousness in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Toronto. Law & Society Review, 41(3), 511-756.

[4] Jacobs, L. (2007). Rights and quarantine during the SARS global health crisis: Differentiated legal consciousness in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Toronto. Law & Society Review, 41(3), 511-756; Teo, P., Yeoh, B. & Ong, S. (2005). SARS in Singapore: surveillance strategies in a globalising city. Health Policy, 72, 279-291; Lai, A. & Tan, S. (2013). Impact of Disasters and Disaster Risk Management in Singapore: A Case Study of Singapore’s Experience in Fighting the SARS Epidemic. ERIA Discussion Paper Series. ERIA-DP-2013-14. Singapore: Ministry of Home Affairs; ASSET (2016). Democracy and human rights under Public Health Emergency (PHE) threat. ASSET Paper Series. Rome: Zadig.

Elisa Pieri is a Lecturer at the University of Manchester, where she has been conducting research on Securing Cities Against Global Pandemics (Simon Fellowship Award 2016-2019). Her work focuses on security, governance of radical uncertainty, science and technology studies and the urban. elisa.pieri@manchester.ac.uk

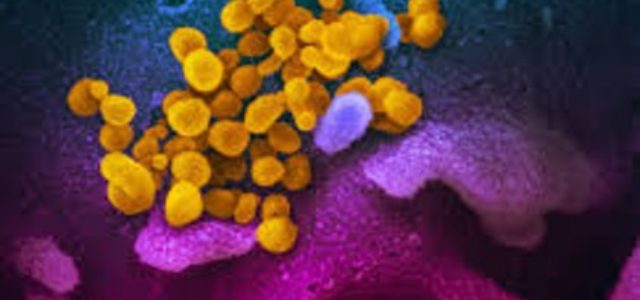

Image Credit: NIAID-RML