Sam Wren-Lewis

Since the election result all the way back in 2019, you’ve probably read a handful of “Why did that happen?” articles attempting to explain why Labour did so badly (or why the Conservatives did so well). You may even have impatiently moved on and read a few “What to do now” articles showing how the Left can rally the troops and get us all out of this mess as quickly as possible. Most likely, you’re bored of these kinds of articles by now.

Well, don’t worry – this isn’t another one. Understanding trends in society and politics requires going beyond simple analyses. The election result cannot be adequately explained by the character traits of political leaders, the accessibility of stock phrases or even the popularity of party policies. Instead, we need to look at the socioeconomic factors behind our moral values and the political behaviours they cause. This article is an attempt at providing a rough idea of what such an analysis would look like. The upshot is that “What to do now” has many answers.

A Very Brief History of Human Development

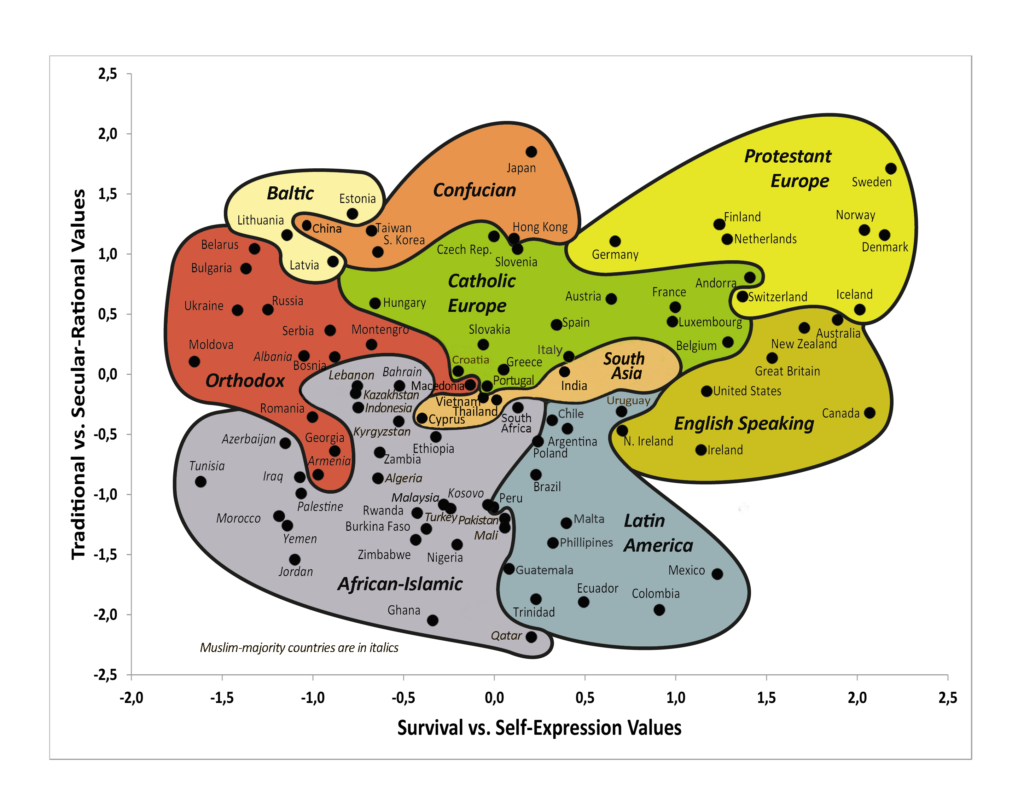

From political science and political psychology we know that people’s moral and political values change depending on their socioeconomic conditions. Differences in values are most obvious between countries because that is where the greatest differences in socioeconomic conditions exist. The World Values Survey, lead by political scientists Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel, has collected people’s values in countries across the world since the 1980s and many of its most important findings can be summarised by the following ‘Global Cultural Map’:

This map shows that people’s moral and political values tend to vary on two major axis. First, the Traditional vs Secular Rational axis: this refers to how much people care about values such as religiosity, national pride, respect for authority, obedience and marriage (or their opposite values). Second, the Survival vs Self-Expression axis: how much people care about security over liberty, non-acceptance of homosexuality, abstinence from political action, and distrust in outsiders (or their opposite values). Simply put, people’s values tend to cluster around two dimensions: how much they care about a) security vs opportunity and b) group identity vs individual autonomy.

Researchers have shown people’s values change over time with changes in socioeconomic conditions. This is a two-step process. Following an increase in standards of living, nations move from traditional values to more secular-rational values. When people are less dependent on their community, they tend to care less about conforming to group authorities and following religious norms and practices. Then, after shifting from an industrial to a knowledge based economy – from factory work to more service based jobs – nations move from survival values to more self-expression values. Within an economically prosperous nation, people can start to care about individual rights and the most vulnerable members of society.

To many, these changes look like progress. Without having to worry about securing food, shelter and protection from violence, people can focus on what makes life worthwhile: developing interests and enjoyments, having loving relationships and caring for the environment.

The important point for the current political climate in the UK is that these differences in values and socioeconomic conditions also exist within nations. For instance, wealthier people who live in cities are more likely to have secular-rational/self-expression values; poorer people who live in rural communities are more likely to have traditional/survival values. We can see the same differences between those on the political left and right.

A Brief Lesson in Political Psychology

People on the left are typically labelled as being more ‘liberal’ or ‘progressive’. Following on from the research discussed above, we can view liberal values as a response to socioeconomic security and opportunity – valuing individual rights and social change. In contrast, conservative values are a response to socioeconomic insecurity and threat – valuing community cohesion and social order. This is why liberals talk about the future and the hope for real change, while conservatives talk about the past and the desire to preserve what we already have.

Another feature of these two different ideologies is their focus on social conditions vs personal agency. According to the liberal value set, there are significant opportunities for social change – we must create the social conditions that help people thrive, especially for the most disadvantaged and vulnerable members of society. In contrast, according to the conservative value set, there are major threats to the social order – we must keep things as they are, and it is the responsibility of individuals and communities to find ways of surviving within the social conditions they have.

It is no surprise that, with these two different mindsets in play, there is very little scope for civil discussions to take place between political divides. According to one side (the left), the world is full of unfair social conditions and opportunities for change. According to the other side (the right), the world is full of threats and we must all do the best we can to keep things in order. We automatically infer these differences in political orientation from the clothes people wear to the activities they enjoy. We are quick to form in-groups and out-groups: ‘Us vs Them’. We think of our group as ‘full of noble, loyal, distinctive individuals’, whereas outsiders appear ‘disgusting, ridiculous, simple, homogeneous, undifferentiated, and interchangeable’. We are right, but they are deeply wrong.

This is not a good state of affairs. But there is an alternative. We can learn from the other side.

The Many Things We Can Do

What if, instead of simply thinking that we are right and they are deeply wrong, we acknowledged the fact that the views of the other side are shaped by entrenched socioeconomic conditions? And what if – and here’s the radical thing – from that perspective, they might be right?

In asking this question, I am not making the point that we shouldn’t disagree with each other. Nor am I saying that we should accept policies or points of view that we believe to be wrong or harmful. My point is that the values of those on the left and right are reasonable responses to socioeconomic conditions. The opinions and policies that they inspire are also responses to those conditions. Let us assume, for example, that we all lived in conditions of extreme deprivation. If our livelihoods were insecure and our communities were constantly under threat, it makes little sense to talk of real social change – we just need to get through our days. And if there really was nothing we could do about our wider circumstances, it makes much more sense to concentrate on our personal choices and behaviours and the strength of our communities. Of course, these are conservative values. My point is that, under certain conditions, they might be perfectly valid.

In working out what to do post-election, we can employ either liberal values or conservatives values or both. From a liberal perspective, things don’t look so good right now. But, we still have the security and opportunities we need for change. We can use these opportunities to change people’s social conditions for the better. This might not happen in the foreseeable future, but the war is long. And these seeds of change have already been sown during the election campaign and with the progressive youth movements of today.

From a more conservative perspective, however, this vision of how we can all ‘move on’ is seriously lacking. People need things to change now, not just in the some distant liberal utopia. We need to overcome the immanent threats that people face to their livelihoods and to their communities. This requires effective political mobilisation and action. If we can’t do this on a political scale right now then we need to focus on strengthening our local communities and making sure that none of our neighbours – or any of the people we really care about – get left behind.

Each of these perspectives make sense within a particular set of socioeconomic conditions. The point I want to make is that they are not mutually exclusive. Sometimes we will have the security and opportunities to create real social change in the long-term – there are things we can do to reform the mainstream media, participative democracy and the voting system. At other times, we must focus on avoiding the immanent threats to people’s lives – we can stand in solidarity and build social movements to change things in the short-term. Sometimes, we should try to change people’s circumstances – provide all members of society with the resources and opportunities they need. At other times, we should concentrate on our own networks and communities – to create local sharing economies, volunteer or build relationships with our neighbours, colleagues and family.

For any social issue, we can engage in this act of political empathy. We can ask: What opportunities there are for changes in the long-term? What threats need to be overcome in the short-term? What social conditions are required to create these changes or overcome these threats? And what can individuals and communities do? If we are asking all these questions then we are thinking both like a liberal and a conservative – we are incorporating the wisdom of both the left and the right. We are learning not just form the other side, but also from the history of human development.

Sam Wren-Lewis is an independent scholar with a PhD from the University of Leeds on the study of wellbeing. He is an Honorary Associate Professor at the University of Nottingham and the author of a number of published papers on topics related to happiness and wellbeing. He is also a self-employed wellbeing consultant, and former Head of Research and Development at Happy City, where we carries out collaborative research and policy work with a wide range of wellbeing policy organisations. He is the author of The Happiness Problem. @wbandhappiness