Olivier Esteves

On 25 May 1963, readers of The Middlesex County Times (Southall Edition) were taken aback by grisly news: the local Scout movement had recently lost as many as thirteen boys, all leaders of troops whose parents had fled to further suburban towns. W.J. Hubbard, the District Scout commissioner, acknowledged that “this was understandable”, because “they feared that their children’s education would be held back”. The explanation given was quite straightforward: “We are losing many Scouters who have been living in that part of the town occupied by our Indian friends”.

Since then, the demographic and ethnic development of places like Southall has sometimes been dubbed “White Flight”. And it was the concomitant White Flight to suburbia and the swift influx of Punjabi Asians to Southall which were at the root of the introduction of “bussing” in the area. Unlike its much more mediatized American counterpart, English “bussing” (or “dispersal”, as it was officially known) consisted in sending busloads of presumably non-Anglophone immigrant pupils to white suburban schools in an effort to address their linguistic deficiency as well as to integrate them more broadly, i.e. to have them adopt the English / British way of life.

This double rationale was trumpeted by circular 7/65 (Department of Education and Science) to promote the dispersal policies. Once it was established that a school had at least “about one third” immigrant children, dispersal was to be operated. This was despite the fact that “immigrant children” had not been defined, and that countless Local Education Authorities did not have appropriate statistics, or were reluctant to introduce such statistics.

Integrationist rationale

Ultimately, only about a dozen Local Education Authorities embraced bussing, at any given point between 1963 (before the circular) and 1987: they were Blackburn, Bradford, Bristol, Halifax, Hounslow, Huddersfield, Leicester, Luton, Smethwick, Southall (Ealing borough) Walsall, West Bromwich, Wolverhampton, and probably Dewsbury and Croydon. Bussing took many different forms, and was more or less aggressively or reluctantly implemented. In Bradford it was quite massive, in Southall it was very massive, with some 2900 pupils of primary age being dispersed when bussing peaked in 1975.

Since circular 7/65 only recommended dispersal, it turned out the four LEAs with the largest number of immigrant children, Inner London Education Authority, Birmingham, Brent and Haringey refused to introduce it. They argued against it on the basis of the preferability of neighbourhood schools, which were (rightly) deemed as comfort zones wherein immigrant communities were more likely to integrate successfully.

Beyond the integrationist rationale serving as a public justification for bussing, what was key was that the Establishment and the local white populations in sites of ethnic clustering feared that their children’s education might “held back” by so rapid an influx of non-Anglophone students. “White Backlash”, then, was at the heat of bussing, particularly in the Southall area, where the Southall Residents Association had some connections with the British National Party, and, to a lesser extent, in Bradford, Blackburn and the West Midlands.

More than anything, what was feared was the development of “immigrant schools” or “ghetto schools”, whose evocation was replete with terrifying images of the United States ghettoes, at a time when Newark, Detroit, Los Angeles has just been set ablaze by violent riots. It is only with this white fear in mind, and the implicit parallels with the United States, that the following declaration by secretary of education Edward Boyle may be understood, after a visit to a Southall primary school in October 1963: “I must regretfully tell the House that one school must be regarded now as irretrievably an immigrant school. The important thing to do is to prevent this happening elsewhere” (Speech to the House of Commons, 03. 12. 1963). It was to forestall such development that bussing was put in motion, for better and very often for worse.

Racial myopia

With some exceptions, bussing proved a failure. One reason was that dispersed, marooned and unwelcome Asian youths faced racist bullying in schools from two to seven miles away from their neighbourhoods, even ten miles in some cases in the borough of Ealing. As a postcolonial aftertaste, it also confirmed to many Asians that somehow they were lesser breeds without the law, since bussing white children to the multiracial inner cities was never an option. This is what Riaz Ahmed, a Bradfordian bussed for a few years in the late 1960s, bitterly recalls:

It was a failure primarily because it was a one-way traffic, not a two-way traffic, I remember it was a couple of lads like me going to white schools, there were ten or twelve of us, and I remember we got bullied, it was terrible, and these are your formative years, you see, very important for your mental development … There should be bussing, but it has to be a two-way traffic, otherwise it will fail.

This viewpoint was echoed by 4/5 of the interviewees in the Southall area, where clearly, racist bullying was the norm in dispersal schools:

“In secondary school we were spat at, our hair pulled, it was standard practice, we were called ‘Pakis’ even by girls in Northolt” (Anjuna Kalsi);

“Some of the teachers were OK. At the beginning it was ‘in your face’ all the time, the racism was raw, they would sing nasty songs, they would beat you up […] I just thought that was it; racism to me as a concept never occurred to me, I never put two and two together. I just got on with it” (Mel Jung);

“In the playground there was one side with Asian kids, the other side with white kids, and it was pure tribalism: taunts, fights, name-calling, etc. We would charge at each other, day in day out, the staff had no problem with that. It was a routine, a daily thing” (Swarn Shoor).

In the archives, only very rarely were such racist bullying prospects envisaged as an actual potentiality. Some individual testimonies or statements by head-teachers in areas such as Nottingham, Manchester, Leeds or London may have served as warnings, but these were either unheard or unheeded in Southall and Bradford in particular. The very rapid influx of immigrants in those two places did catch local public authorities off-guard. And it is clear that there was a great deal of unpreparedness about bussing’s introduction. But “unpreparedness” does not tell the whole story, really, for the introduction of dispersal owes a lot to a myopic reading of the social world in which New Commonwealth immigrants evolved.

The DES’s bureaucratic ethos produced some state simplifications and some “planning for abstract citizens”, a phrase borrowed from James C. Scott’s Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Indeed, despite the DES’s flexibility in applying the “about one third” quota, it was never expected – there is no trace of this in archives – that many schools where immigrant children would be sent would be far from multiracial havens of tolerance. In this sense, the state simplifications which paved the way for dispersal were tantamount to a form of racial myopia. Or, to quote Scott, “What is striking, of course, is that such subjects – like the ‘unmarked citizens’ of liberal theory – have, for the purposes of the planning exercise, no gender, no tastes, no history, no values, no opinions or original ideas, no traditions and no distinctive personalities to contribute to their enterprise”. Similarly, for the purpose of bussing, the white children of West Yorkshire or Ealing suburban schools were supposed to have no prejudice, no hostility, no ingrained proclivity to look down upon those they saw as “the Pakis on the bus”.

The costs of becoming like others

With hindsight, the history of English bussing is interspersed with some baffling ironies. To integrate and therefore “become like others”, dispersed Asian children had to go through a daily process whereby they were constantly reminded of their radical Otherness in the eyes of autochthonous whites. To adopt the English / British of life, they had to be seen as “The Pakis on the bus”. To internalize the ways of British democracy, they had to be forcefully integrated regardless of the fact that the Education Act of 1944 supposedly guaranteed “parental choice” on what was to become, a few decades later, a real education market.

After the Race Relations Act of 1968, dispersal was politically and morally bankrupt, although it only petered out in Southall and Bradford in 1980-1. Indeed, it rested on some ill-defined “immigrant children” category, which in practice was colour-based. For there was never any question of bussing non-Anglophone Ealing Polish children or non-Anglophone Italian children in Bedford, whereas many Anglophone Asians from Uganda and Kenya were indeed bussed. Some of these are interviewed above.

It behoved the Race Relations Board, which became the Commission for Racial Equality in 1976, to expose this blatant anomaly. And it is no surprise that Bradford and Southall, two places where bussing operated on a massive scale, also became in the 1970s and 1980s hotbeds of ethnic minority resistance against racism, be it in the form of the Southall Youth Movement, the Southall Black Sisters or the Bradford-12. Although none of these were actually caused by bussing, it remains that the long-drawn resistance movement against bussing was a crucial backcloth to make sense of such locally-based militancy.

Olivier Esteves is Professor of British Studies at Lille University. He works on the sociology and history of immigration and race relations. He is the author of De l’invisibilité à l’islamophobie : les musulmans britanniques (1945-2010) (Presses de Sciences Po, 2011) and The ‘Desegregation’ of English Schools: Bussing, Race and Urban Space, 1960s–80s (Manchester University Press, 2018).

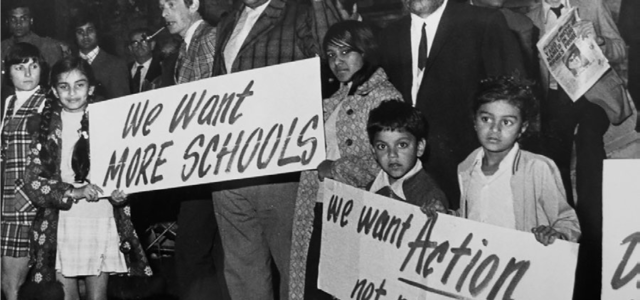

Image Credit: A protest against bussing in Southall, 1978 (IWA Southall archives).