Anthony Kevins and Kees van Kersbergen

This section of Discover Society is provided in collaboration with the journal, Policy and Politics. It is curated by Sarah Brown.

This section of Discover Society is provided in collaboration with the journal, Policy and Politics. It is curated by Sarah Brown.

The generous “universal” welfare states of Scandinavia offer a range of perks that foreigners often have a hard time even imagining. In exchange for paying higher taxes, citizens across the income spectrum gain access to a wide array of social programmes and transfers. There’s a lot to praise. But does the generosity and broad accessibility of these welfare states reinforce the dividing line between, for example, native Danes and newcomers to Denmark? In our recent Policy & Politics article, we set out to answer this question through a comparison of the Danish and Canadian welfare states.

Thanks to a key set of similarities and differences, comparing these two countries helps us to better understand the relationship between welfare state universalism and immigrant integration. Both countries share a long history of using social policy to create a sense of allegiance to the national community. A long line of Danish and Canadian governments have done so by appealing to “universalism”, tying welfare state access to citizenship or residency (rather than, for example, to an individual’s income level or labour market participation).

Yet these two countries exhibit different degrees of generosity and different patterns of welfare state-immigrant dynamics. On the one hand, Canada is, by international standards, far from a big spender on its welfare state – whether compared to Denmark, the OECD average, or even other modest “liberal” welfare states like the US and the UK. On the other, even though a generous universalist welfare state should (according to past research) minimize concerns about fraud and benefit misuse by certain groups, it is in classically ‘universalist’ Denmark, rather than less-than-generous Canada, that we see these worries flourishing vis-à-vis immigrants.

Given this paradox, we set out to explore the connection between universalism and immigrant integration. Two questions are at the core of our investigation. First, what, exactly, is a “universalist welfare state”? And second, how can universalism help us to understand immigrant integration in Denmark and Canada?

Universalism as a Tool of ‘Statecraft’

Before turning to answer these questions, it’s important to highlight that social policy does in fact matter for integration. Since its creation, the welfare state has been a key tool for connecting people from diverse regional, linguistic, religious, and class groups and for fostering solidarity among them. Governments have used social policy for “statecraft,” pushing forward integration based on territorial bonds while at the same time diffusing inter-class tensions.

Universalism, with its focus on delivering benefits to citizens as citizens – rather than, for example, by virtue of having made enough social insurance contributions – is particularly good at building a sense of community. On the one hand, the range of available benefits shores up the link between citizens and the state, while on the other, the scope of benefit access serves to reinforce community boundaries.

Indeed, architects of social programmes have often used the language of universalism and pointed to social integration as a major goal of these projects. While immigrant groups were typically not the originally intended target of these policies, a long line of research suggests that welfare states nevertheless shape the integration of newcomers into society. Key here are the links among citizens (both as individuals and as members of diverse groups) and between citizens and the state – which are arguably more likely to develop vis-à-vis immigrants within generous welfare states.

Yet we might also ask whether universalism can, in the face of increasing migration, still act as a tool of statecraft and social integration. Immigration is not always frictionless: it can pose a challenge to community solidarity, or at least bring about a new conception of who belongs to the community.

Rethinking Universalism

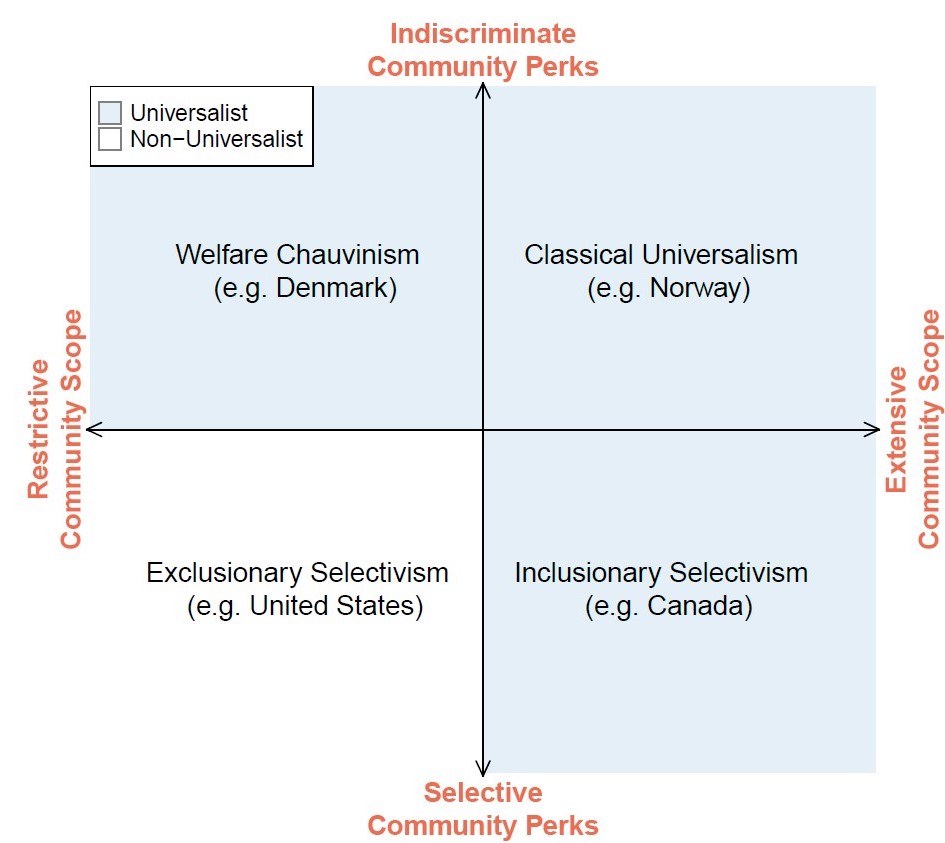

To better understand these frictions and their relationship to the welfare state, we believe that the concept of “universalism” needs rethinking. We argue that two major universalist traits need to be distinguished: community perks and community scope. In the past, researchers have usually pointed to generous, indiscriminate community perks as the marker of universalism, viewing them as central to a process of self-reinforcing solidarity. We argue, however, that an inclusive community scope can serve a similar function – and that the mix of perks and scope in a given country has important implications for migrant integration into the community.

Consider first the community perks-based definition of universalism. States differ dramatically in the range of benefits, whether in cash transfers or services, that they make available to the average citizen or resident. Social programmes may be narrowly targeted (that is, selective) or widely accessible (that is, indiscriminate) for community members. The sum total of these programmes will be a set of perks that are more or less selective.

But although this perks-based approach is the standard generally used by researchers, we argue that something important is missing from the picture. Crucially, if we think seriously about the idea of community scope, we realize that the group of individuals that is eligible to receive a given perk will at the same time be more or less extensive, depending on the country and the benefit.

Let’s apply this framework to a concrete example: healthcare. On the one hand, access to government healthcare within a state might be available to all community members (that is, an indiscriminate community perk) or it might only be available to those of them who are unemployed (that is, a selective community perk). In either instance, however, the scope of the “community” could be relatively inclusive – for example, with benefits available to all unemployed residents, or to all persons passing through the country – or it could be relatively exclusive – for example, excluding asylum seekers and residents who have yet to meet lengthy stay requirements. Universalism might thus involve relatively indiscriminate community perks, relatively inclusive community scope, or both at the same time.

Figure 1 summarizes this rethinking of universalism. In our view, universalism has at least two dimensions: community scope (on our figure’s x-axis) and community perks (on our figure’s y-axis). Several different sorts of welfare states can be considered “universalist,” but only if one realises that the meaning of universalism varies across the cases. The Norwegian welfare state is the classical universalist welfare state, with indiscriminate community perks as well as an extensive community scope. The Canadian welfare state stands out for its equally extensive community scope, but its benefits are generally more selective. The Danish welfare state, in turn, has maintained its indiscriminate community perks, but restricted the community scope. Finally, the US is excluded from the universalist “family” of welfare states, as its community perks are broadly selective and its community scope relatively restrictive.

Figure 1: Rethinking universalism

Comparing Denmark and Canada

Our rethinking of universalism has important implications for how we think about existing welfare states. We argue that variation in available “community perks” is crucial for understanding how universalist social policy affects solidarity and the integration of immigrants into the national community.

In Denmark, the generous set of universalist perks has reinforced – somewhat counterintuitively – the division between those who are in and outside of the national community. Given that newcomers gain access to extensive community perks, the potential cost of letting immigrants in is seen to be higher. In the eyes of the native population, it therefore becomes more important to monitor immigrant behaviour – to make sure that newcomers behave like “true Danes” – in order to keep the generous welfare state afloat.

In Canada, by contrast, the comparative stinginess of the welfare state helps to soften the dividing line between the native-born population and newcomers to the country. The “universalism” of the minimalist Canadian welfare state is thus one that reinforces a more inclusive Canadian identity: immigrants are (from a comparative perspective) relatively easily incorporated into the national community, but the welfare state perks that go along with community membership are fairly limited.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that we should set out to cut back the welfare state today so that we can all be more welcoming to immigrants tomorrow. As our comparison of Canada and Denmark also highlights, a generous welfare state is a far more effective vehicle for achieving other worthy goals, such as reducing poverty – including, crucially, for immigrants themselves.

Rather, our study highlights the need to address certain tensions generated by generous universalist welfare states before it’s too late: without careful policy attention, the broad, solidarity-building capacity of generous community perks may fizzle out, instead reinforcing the dividing line between the deserving “us” and the unworthy “them”.

Anthony Kevins is a Marie Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at the Utrecht University School of Governance. Kees van Kersbergen is a Professor of Comparative Politics at Aarhus University.

Image: Paul Weaver CC BY-NC-SA 2.0