Les Back

Paul Gilroy’s book There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation published in 1987 is now in its thirties. It is a book that is much more than a thesis, or an argument about the damaging mutual implication of racism and nationalism: it is a book that made and makes the world differently. It helped many of us think that the things we cared about were legitimate and possible, I feel that as a personal debt and I am sure many of its readers will share that feeling. For that task of becoming more than what others have decided for you is not an easy thing. It wasn’t easy in the 1970s and 1980s and it certainly is not easy now.

I think one of the things that is distinctive about Paul Gilroy’s thought is his unnerving capacity to anticipate, read and interpret the damage that the British empire and colonialism did to both the colonized but also to the colonizers. The double standards of imperialism fostered in the colony a sense that Britain was the ‘Mother country’ and yet at the same time nationalists from Churchill to Powell were steadfast in their desire to place them at a distance and to ‘keep Britain white’. So, in this sense it is a book that anticipated the circumstances that produced the recent Windrush scandal where citizen-migrants, having lived in the Mother country for seventy years, were told to ‘go back home’.

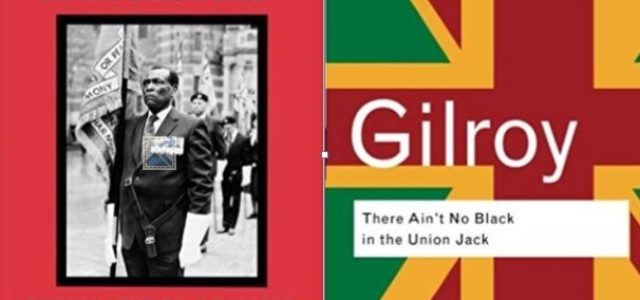

At the same time, Gilroy is equally attentive to the vital culture nestling in the shadows of the imperial metropole. It is a book that confronts nationalist erasure and this is conveyed visually in the cover. Teaching the book now, I need to remind students that the title is taken from a football chant sung during the 1970s and 1980s by England fans: ‘There ain’t no black in the Union Jack, send the bastards back.’ Captured in the song is the exclusive coupling of race and nation. The cover overlays this transcribed hateful voice with an image of a black veteran, bearing the colors of his regiment on a winter morning in London.

The choice of the cover image reflects one of the key strands in Paul’s critical oeuvre which both exposes the racially exclusive dimensions of British nationalism that is centered on Englishness and develops a counter narrative of black and brown presence that is an integral part of the story of British social formation. The image is reminiscent of Roland Barthes’ discussion in Mythologies of the French colonial soldier on the cover of Paris Match magazine saluting the Tricolor. Barthes presents this as a mythic symbol of French imperialism. The image does not hide its colonial past but rather distorts it and as a result this history is ‘changed into gestures’ (Barthes 2012: 272).

The image of the soldier on Paul’s cover has a different quality. The soldier’s look is stoic and a chest full of medals belies the price he has paid to have the right to hold his regiment’s flag adorned with the words ‘harmony’ and ‘peace.’ Paul’s work points – at least tacitly – to an alternative cultural politics of reckoning and refiguring what our relationship to that past might be as it circles around our present and continues to govern it. Although, there is no easy accommodation in his thought he does give us some tools to confront that past. This is why the book has remained vital. It is a book to live in, with and through: a book you are transformed by after reading it and one that makes new ways of thinking and connections possible rather than merely parroting existing ones.

I think one of the most powerfully relevant sections of the book is Paul’s discussion of Enoch Powell and the links between Churchillism and Powellism and also how this linked to the authoritarian populism of the Thatcher governments. Gilroy points out that Churchill and the Conservative cabinet discussed fighting the 1955 election with the slogan ‘Keep Britain White’. This year has also seen the passing of the fiftieth anniversary of Powell’s ‘Rivers of blood speech.’ All those tribunes of race and nation like Powell felt a special responsibility to be the protectors of ‘working class opinion’ too before the idea of the white working class was invented. There is a warning here that seems all too chillingly relevant. Paul commented that the working class configured within the cultural politics of race and has more to lose than its chains. How hauntingly true that remains.

The book argued that it is within the professions of the media and within the legal system that the work of racism is centered. Black youth in the Metropolis were made emblematic of a specific kind of criminality and lawlessness. Forms of policing and criminalization practiced in the hinterlands of empire were repatriated and used against those who are cast as ‘lesser breeds without the law’. How chilling an echo of this it was to hear during in a discussion of ‘knife crime’ – the latest moral panic about race and crime – on BBC TV show Question Time that a genteel bespectacled white middle-class man could say confidently without shame: ‘Don’t forget it is a particular breed of human being who can repeatedly put a knife into another person and those people should be dealt with like the cancer they are and exterminated.’ The history and force of these cultural pathologies are still unfolding even when they are expressed without a specific reference to race.

Paul is an epicure of intelligent insight particularly of the kind that that rubs against the grain of ignorance or hubris. You can see that when his face lights, or when he laughs in worldless approval in response to a comment that puts its finger on something important. I want to make say a few words about how he does his work, I won’t use the word methodology. Let’s call it something else – let’s call it his intellectual craft. I think some of these qualities are there in There Ain’t No Black. He has an incredibly capacity to move across a reading of political and cultural theory and the sentiments of black expressive cultures while giving them with equal seriousness and attention. He has an open curiosity that is as much attentive to the artistry of Congo Natty as to the exponents of contemporary English folk music like Chris Wood. The idea of decolonizing knowledge doesn’t quite capture the quality of mind he has. It is a deep and radical openness to culture on a worldly scale. Also, Paul is a committed to doing the work of critique with rigour and care.

This wasn’t necessarily appreciated at the time and it is salutary to remember that Colin Prescod wrote a grudging review of the book in Race and Class. He commented there was something ‘very European in the way he [Gilroy] expresses his concerns’ (Prescod, 1988: 97). However, Colin Prescod did write approvingly that he liked ‘Smiley Culture being described as an organic intellectual’ (Prescod 1988: 99). It’s a good example for Paul has this capacity to draw connections between Gramsci and the stringing up of a sound system and what he called the ‘kinetic orality’ of the MCs on the Mic. These are acts of language that transform our understanding of what is at stake when the lights go down and the volume is turned up. Paul was attuned to the significance of these new patterns of culture and expression and what might be learned from paying serious attention to that voice. Also, those familiar references draw us in. If you like Smiley Culture’s Cockney Translation or Laurel & Hardy’s You’re Nicked then you also going to have to deal with social movements theory too and vice versa. It’s a book that crackles with ideas and evocative phases.

Here culture is conceived not as hermetically closed system regulated by ethnic absolutism of any kind. The book offers an alternative kind of cultural politics too. One that is situated in the rhythms of life that have their own protocols and ethical maxims and terms of access. Paul’s model of culture is not a closed system, the soundproofing doesn’t hold and particularly within urban localities the terms are negotiated in real time where those who can or cannot access them is re-defined in potentially radical and transformative ways. It’s also why he says that regional or local cultures might be a space where a different cultural politics of race might emerge. That’s why I think he sides in the book with the example of rock against racism as a resource to think about what a lived anti-racist culture might look, sound and feel like.

I want to say one further thing about Paul and that is his courage and intellectual bravery. In our age of academic timidity and conservatism that is an important example. I think bears saying just how tough it was for him and others in his generation to create the things they made. So much is left out in the portrait of Paul as the world famous cultural theorist… former Yale Chair… Professor of Hip Hop etc. The truth is the white professorate at the time he wrote this book tried to shut him down. Criminologist Jock Young wrote in a review of The Empire Strikes Back – which Paul contributed centrally – that it was a ‘a work of propaganda not scholarship.’ Sociologist, and early figure in the New Left, John Rex blocked Paul from getting jobs and more than that he boasted about. This kind of behavior was open and unashamed. By contrast, Paul has always encouraged and facilitated younger scholars and his popularity with them is a testament to that.

Paul has spoken recently of being part of a generation of black artist and writers who came of age in a situation where they were constantly being told to go ‘back home.’ There was no place to go ‘back to’ and the only options was to make a world fit for themselves here and now. I think that is part of what the book achieves it give new ideas space, it makes a world almost as much as it reflects on it. In this sense, I think There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack is a book that made the ideas that followed it possible and gave a generation of scholar license to think differently about the relationship between race and nation.

References:

Barthes, R. (2012) Mythologies New York: Hill and Wang. (Originally published 1957).

Gilroy, Paul (1987) There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: the cultural politics of race and nation London: Hutchinson.

Prescod, C. (1988) Book Review: ‘There Ain’t no Black in the Union Jack’: the cultural politics of race and nation By Paul Gilroy, Race and Class, 29 (4): 97-100

Les Back is Professor of Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London