Muneeb Hafiz

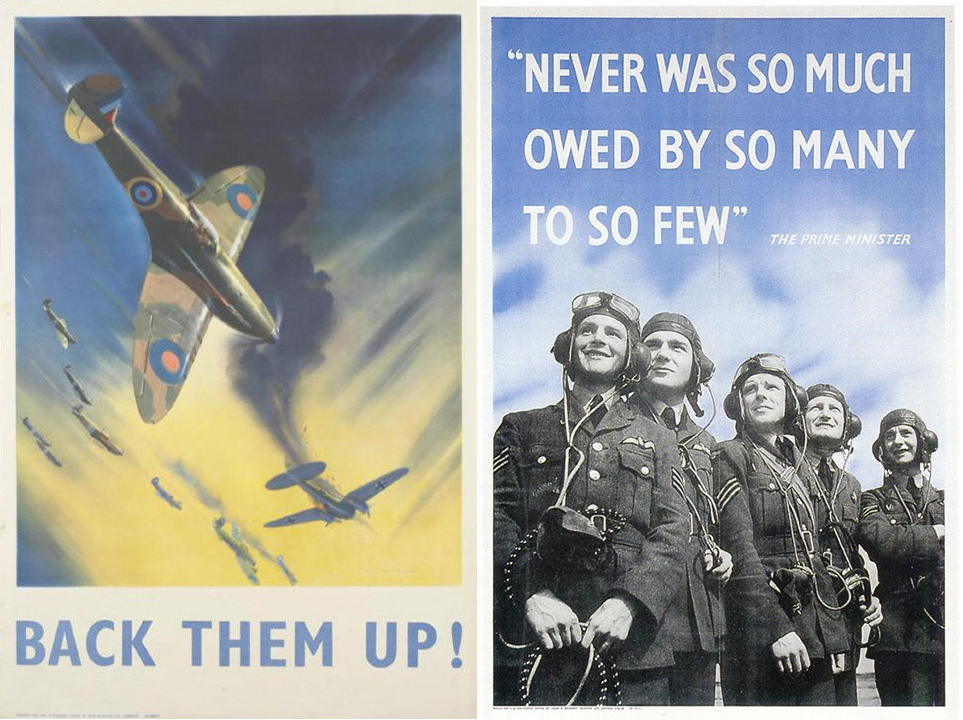

The Supermarine Spitfire was unveiled to the British public on Saturday 27th June, 1936 at the RAF-Hendon air-display. Full-scale production was supposed to begin immediately at Supermarine’s small but well-known facility in Woolston. But it quickly became clear that the order of 310 aircraft placed by the Air Ministry could not be fulfilled within the fifteen-month timescale guaranteed by Sir Robert Maclean, director of Vickers-Armstrong of which Supermarine Aviation Works was a subsidiary. Nevertheless, by mid-1938, the first production Spitfire rolled of the assembly-line and the rest, as they say, is history. Then as now, the Spitfire is the image of the Royal Air Force in public consciousness and its silhouette an elemental icon in the British cultural imaginary.

On 15th September of this year, the Department for International Trade and Conservative MP Liam Fox – Secretary of State for International Trade and former Secretary of Defence – were delighted to inform us that they will be supporting Boultbee’s restoration of the Spitfire which, when complete, will embark on an around-the-world flight in summer 2019. #ExportingisGREAT we are told. The restoration of the Spitfire is, I think, indicative of a broader set of developments, by no means new, in Brexit Britain. At the very least there are a set of questions worth pausing over. To what extent are we being increasingly habituated to martial images and their attendant connotations of danger, adventure, national unity, racial purity and triumph? What currency might they have in contemporary Britain and its climate of xenophobia, racism, anxieties of national decline, and hopes for renewed greatness? Finally, why these images and why now?

Race and Imperial Propaganda in Britain

There are some potentially fruitful parallels to be drawn between popular imagery in contemporary British cultural life and imperial propagandist activity of the 19th and 20th century. The British, it has often been said, were indifferent to imperialism. Empire and the imperial idea were sophisticated concepts and had been the preserve of an elite, and a fractured one at that. There was also, so the story goes, a distinct lack of widespread ideological commitment to, and almost complete ignorance of, the alien, faraway territories of the Empire and the economic/political dimensions of the imperial connection. By the 1920s, any imperial sentiment was destroyed by the First World War and by the time the era of decolonisation came about in earnest, the Empire was already forgotten. This conventional wisdom imagines a national past in which little is known about the realities of Empire, with even less cultural investment in its ideas beyond Empire as a source of nostalgic philately.

A similar mode of detachment, conventional wisdom continues, comprises the British relationship to propaganda – “the transmission of ideas and values from one person, or groups of persons, to another, with the specific intention of influencing the recipients’ attitudes in such a way that the interests of its authors will be enhanced.” Propaganda did not come easy to the British. It was only genuinely contemplated in the desperate conditions of the two World Wars, and reluctantly at that. Domestic propaganda was, then, virtually unknown.

But upon closer inspection and some broader historical literacy, the restoration of the Spitfire, that blessed icon of Brit doggedness, courage and action, ahead of a summer world tour next year, appears to challenge conventional wisdom. And this scepticism can be substantiated by the historical record. Imperial propaganda was the one area of official propagandist activity which seemed to be widely acceptable. Interestingly, the government effort on the Homefront was never considerable, mostly because it was unnecessary. Why? Because a wide-variety of non-governmental agencies founded in the later 19th century were quickly able to extend and embed their ideas and influence into the porous terrain of British cultural and institutional life.

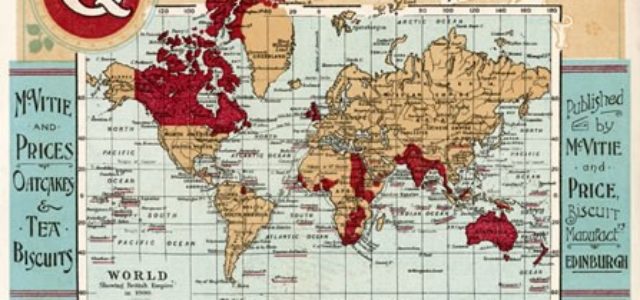

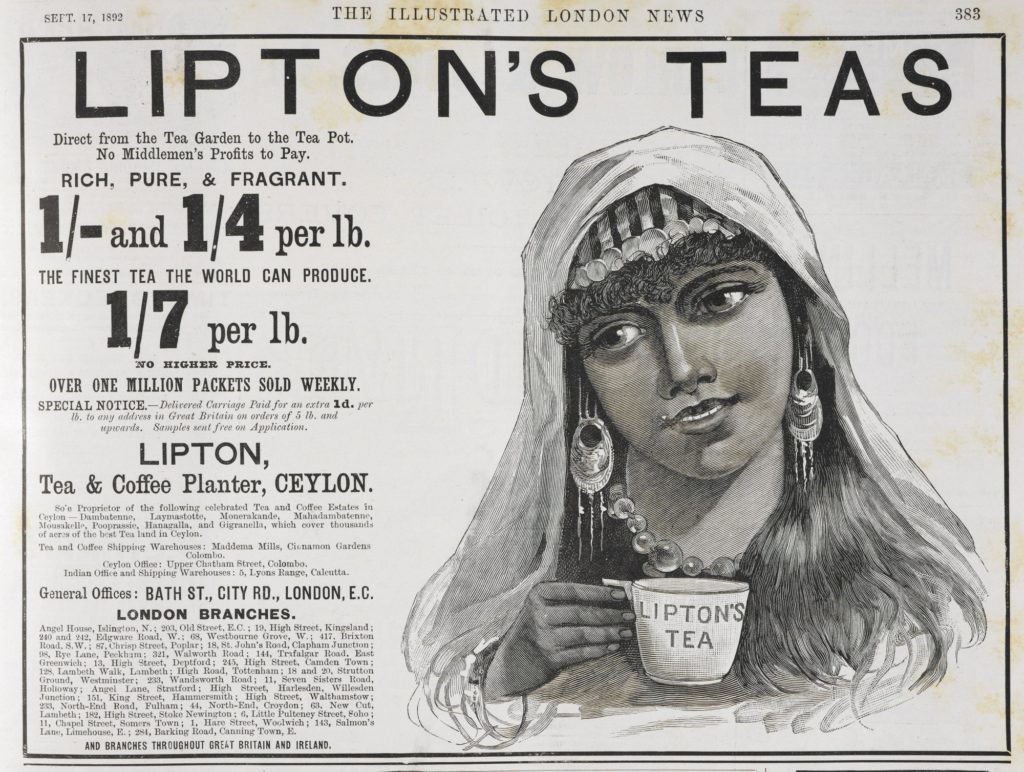

Crucial for this process were the new advertising techniques, a widespread craving for visual representations of the world and events, and the availability of printed and visual materials at prices low enough as to make them accessible to almost every home. Companies creating and supplying these new tastes, not just for representation but also for exotica, were concerned not just to sell their own goods but the world system which produced them. It is no coincidence that the most innovative advertisers of the day were also those companies dependent on the imperial economic nexus, bringing home to the metropole, tea, chocolate, soaps, oils, tobacco, meat extracts, and a wide array of colonial tales of adventure and their protagonists. These companies set out “not only to illustrate a romantic view of imperial origins, a pride in national possession of what Joseph Chamberlain called the ‘imperial estates’, but also to identify themselves with royal and military events, and to score from the contemporary cult of personality.”

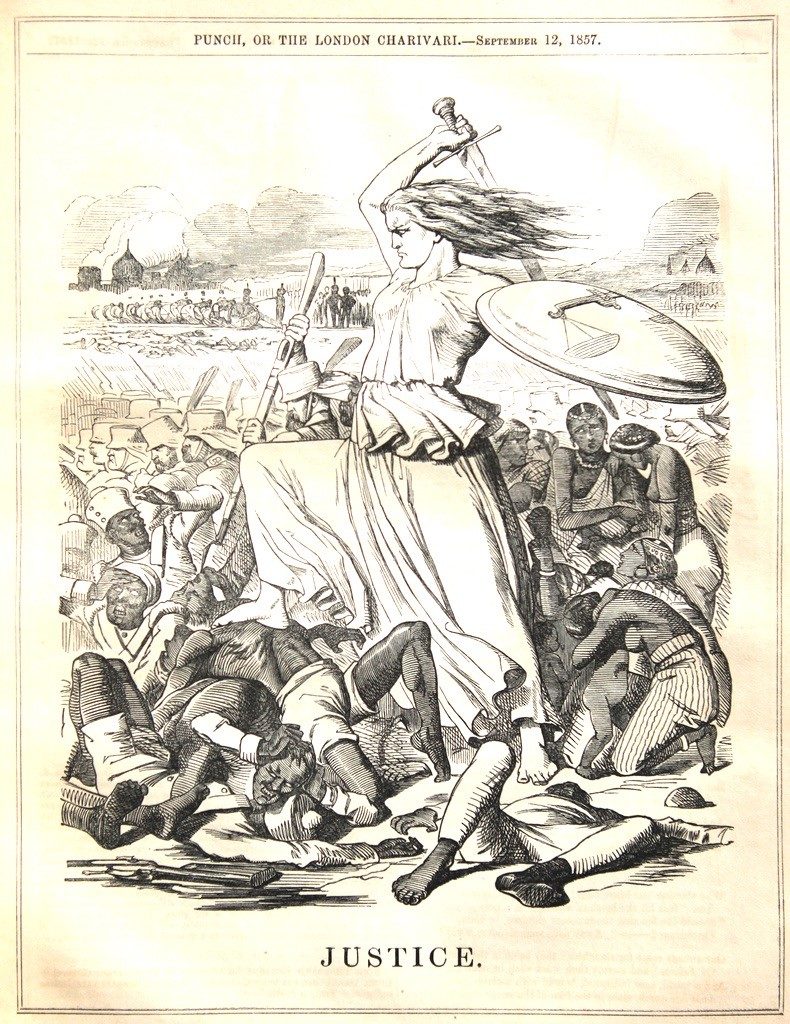

The institutional realm was equally invested in the imperial idea. The educational system, for example, bought in to it in the form of teaching manuals and school textbooks, and their popular histories. The work of English historian and political essayist, J.R. Seeley is of crucial importance and in which the alleged gloom and pessimism of the late Victorian period is not borne out. History for Seeley was meant to stimulate exertions on behalf of the nation and to raise the morale of its members. Imperial expansion was, then, to be seen as the moral of British history and acted as the key to the future. Similarly, the phenomenal boom of the music hall in the 1870s often reflected the dominant imperial ethos of the day and, crucially, appealed to all social classes. There were, of course, official attempts to control the sometimes subversive output of the music hall through fire and licensing regulations, the self-censorship of its impresarios and the outright censorship of Anti-Establishment songs in favour of royalist, militarist, and imperial nationalist performances. Likewise, the Victorian melodrama was a staple of imperial theatre where imperial subjects were a perfect opportunity to externalise villainy: “the corrupt rajah, the ludicrous Chinese or Japanese nobleman, the barbarous ‘fuzzy wuzzy’ or black” often faced a “cross-class brotherhood of heroism, British officer and ranker together.” The moral stereotyping of melodrama with a powerful racial twist was on full-display with the popular Eastern themes found in Barrymore’s El Hyder (1818), Moncrieff’s The Cataract of the Ganges (1823), Cetewayo at Last (1882) and The Indian Mutiny (1892).

Regardless, there was a widespread, quotidian racism and militarism, from products in the home to music halls and theatre; in the uniformed youth movements, such as Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, to the churches and missionary societies of the day. All came to embrace (and not unprofitably) the new imperial nationalism.

The overriding question, however, was to what extent the essentially middle-class ethos concerning Empire was transferred to the other social classes through the potent mechanisms of printing, photography, spectacle and pageant. And for our contemporary purposes, to what extent do the prevailing discourses surrounding the promises of post-Brexit nationhood bespeak this history of imperial propaganda, and its mobilisation of non-elite cultural and ideological investment.

“The Rhodes Colossus” published after British businessman, mining magnate and proponent of the Anglo-Saxons as “the first race in the world,” Cecil Rhodes announced plans for a telegraph line from Cape Town to Cairo in 1892.

As the historian John Mackenzie’s valuable work has shown us, an ideological formation which was constituted out of the intellectual, national, and global conditions of Empire during the late Victorian era, synthesised “a renewed militarism, a devotion to royalty, and identification and worship of national heroes, together with a contemporary cult of personality, and racial ideas associated with Social Darwinism to produce a new type of patriotism derived from Britain’s unique imperial mission.” It was a common-sense – though not uncontested – truth that Empire had the power to elevate not only the ‘backward’ world of other races, but to regenerate the British themselves, and to raise them from the gloom and apprehension of the later 19th century. Creating a national purpose with highly moralised racial and deeply racialized moral content would lead to class conciliation. In sum, there were domestic economic, political and social advantages of “selling” the Empire, literally and figuratively, and to which the restoration of the Spitfire might be related. Producing oneself as a racist subject in everyday attachments to the empire, it’s central figures and stolen profits was a cross-class process; rich and poor, old and young alike.

Requiem for an Empire

23rd June 2016 saw Britain vote to leave the European Union. It promised to put the Great back into Great Britain. Leaving the EU so that “we can survive and thrive as never before,” and which “gives us the chance to start thinking globally and, by the way, bringing prices down for consumers.” And that “at home and abroad the negative consequences are being wildly overdone, and the upside is being ignored.” It was the vision of a future Britain bought and paid for by a rich elite posing to care deeply about (white, hence deserving) working class needs, and promising to compensate for promises undelivered due to EU legislative overreach and mass immigration as the legitimate basis for their resentment.

Hubristic and based on an exaggerated sense of its place in the world, the long process of ‘divorce’ negotiations have time and again exposed the decline of the once great Empire, which has come as a surprise to no-one but the nation itself. Popular visions for post-Brexit futures with respect to trade partners and new prosperities to replace the EU are equally revealing. Often invoking “a shared history and cultural ties,” grand plans for the African continent (in which British companies control more than $1 trillion worth of Africa’s key resources) and the Commonwealth (a good number of members of which are attempting to sue the British government for reparations for four centuries of slavery) as sources of post-Brexit enrichment are presented matter-of-factly. These schemes are as astonishing in their repression of historical fact as in their delusional self-worth about what Britain has to offer them.

These “shared ties” bespeak, of course, a brutal imperial past of theft, violence and death. The dream of “Empire 2.0,” as it has been labelled is blinded by a nostalgia for something that never existed and deeply ignorant to our contemporary realities in which black and brown people are regarded with contempt, suspicion, racism, Islamophobia, and its attendant forms of violence on the rise. It is perhaps not so surprising then that also in 2016, the respondents of a YouGov poll who thought the Empire was a source of pride outnumbered those for whom it was a source of shame by three to one; that the Empire tended to leave its colonies better off than worse off by more than three to one; and with over a third responding they would “like it if Britain still had an Empire.”

Theatrical release poster for Darkest Hour complete with union jack, Spitfire, blue skies and national unity.

Alternatively, revered director Christopher Nolan’s film, Dunkirk, depicting the evacuation of the British Army from the French port during a fierce battle of World War II, was released in July 2017 and was lauded near-universally by critics, grossing over half a billion dollars worldwide. Released around a similar time was Jonathan Teplitzky’s Churchill (2017) and Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour (2018) with passionate portrayals of Winston Churchill in the midst of constant Allied defeats to the massive Wehrmacht.

These martial images of the brave pilots of Spitfires and Hurricanes, of Churchill’s supreme talent for stirring rhetoric and a fine turn of phrase have achieved canonical status in the national memory. From critically-acclaimed epics, to the frequent pageantry definitive of royal family occasions, to school curricula, these same narratives and mythic moments of national becoming and unity continue to dominate and retain a special grip on Britain’s culture and self-understanding. The trouble with this idea of culture is that it entails not only venerating one’s own culture over or at the expense of others. But also, as Edward Said reminds us, “thinking of it as somehow divorced from, because transcending, the everyday world…. Culture conceived in this way can become a protective enclosure.”

The deep ignorance or romanticisation of the imperial dimensions of these moments and characters so often seen on screens and heard from historians and politicians alike finds solace in the protective enclosure. From the total absence of the vital role played by South Asian and East African Divisions during the war, to Churchill’s ghastly and well-documented racism and central role in the Bengal famine, these moments of Britain’s imperial greatness are largely sanitised yet dramatized in a similar fashion to the imperial propaganda found in the music halls and theatres of the late-19th and 20th century; the adverts for Empire in school textbooks, biscuit tins and Lipton, Horniman, Mazawattee or the C.W.S. teaboxes; and the collectible sets of cigarette cards of W.D.& H.O. Wills, John Player, Churchman and Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, all of them revelling in the cult of personality.

These are not isolated instances of World War II/colonial revisionism. There has been a slew of texts which depict the British Raj – the jewel of Empire – from various perspectives: Victoria & Abdul, Viceroy’s House, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel films (and the BBC documentary, The Real Marigold Hotel), The Good Karma Hospital are just a few. Selling the Empire, or as has always been the case, a version of it, is still profitable it seems.

Ethnic Diversity, White Fragility

With this culture of ignorance in mind, is it any wonder then that the Academy of Ideas would think to organise an event titled “Is Rising Ethnic Diversity a Threat to the West?”

The fragility.

With institutionalised and commodified amnesia as our context, their pathological motivations become clearer, though no less destructive for being so. The fact that the title has since been changed to “Immigration and Diversity Politics: A Challenge to Liberal Democracy” is immaterial. They have shown their hand.

In the aftermath of imperialism, the task becomes to justify its prolonged existence, its violent techniques, and its necessity to any future successes formerly colonised/occupied nations might later experience. Such a massive and brazen project of legitimation aims to conceal either guilt or fear. Or both. Guilt for what has been done in the name of queen, country, liberal democracy, the West. Fear of the possibility of a demand for retribution or reparation from those whose ancestors and living relatives have been enslaved, dominated, exploited, raped and killed. The human lives, pieces of earth, and obscene racial subsidies systemically, systematically and creatively plundered to bankroll the same project of the West which is now apparently under threat.

However, we might also answer affirmatively to the question. Yes, the presence of bodies and languages of the postcolony in former metropoles do indeed threaten the West. They threaten the West to reflect on the lies, false names, violence and spilt blood that has been paradigmatic to its formation. They threaten the coherence of the very idea of ‘West’ itself for having been so fundamentally defined by an absence of the ‘backward’ Other, with a litany of grandiose democratic values forgotten and promises undelivered. In the face of white ignorance, denial, comfort, and fragility, they refuse to be exhausted in the effort to claim a share of the world of which we are all of us coinheritors and stewards. They expose the cracks in the protective enclosure.

With the West’s strong track record of despotic means for perfidious ends lying restlessly in the realm of the repressed, framing multiplicity as a threat to democracy brings to the light of day the banality of those who cling to the idea, as angst-ridden, jealous, and fearful for no longer being the centre of attention in a world that is having more interesting conversations in languages they don’t understand. But it goes much deeper. For they know not what will be left of their frightened selves if there is no Other to hate, abuse, malign, pathologise, marginalise, surveil, dehumanise. When Empire ceases to be a signifier of national greatness and self-confidence, but instead a source of the diseases of institutional racism and cultural callousness, claims of historical virtue and white victimhood become incoherent. What is threatening about ethnic diversity is that it is living, incontrovertible proof of what Britain, Europe, the West has apparently yet to learn. It is not the world but only a part of it.

The political theorist, Uday Singh Mehta summarises it well in Liberalism and Empire when he says: “Britain’s view of itself as a democracy in the nineteenth century…was not weakened as far as its liberal political thinkers were concerned by its undemocratic and despotic rule over millions of natives in the Empire, and which was rationalised by many of them as just and in keeping with the natives’ own traditions.” But in the ongoing aftermath of the Wars on/of Terror; rising levels of inequality and poverty starkly evident on our streets; systematic discrimination and institutionalised racisms; in sum, varying degrees of dehumanisation, it is worth asking what this manufactured dissonance between what ‘we’ do and what ‘they’ deserve reveals about the quality of British democracy.

While white supremacist nationalism and racist logics are threats to any genuine striving for democracy, they are also inherently stupid for having premised their own humanity on their (in)ability to disprove the full or equal humanity of racialized/ethnicized others. It is this baseness in the guise of informed debate, free speech or the marketplace of ideas all too often allied with coercion, that has proven itself time and again to be a threat to the world. Imperial propaganda attesting to the salvific and regenerative project of empire has metamorphosed into resentment and romanticism shown in Brexit, popular culture and the academy of ideas alike.

Towards new images of the nation

Brexit Britain is of course not the same Britain of its imperial heights. And despite the self-image of some of its actors, even during the heydays of Empire the nation was not all that serene. And never was the mother-country, never mind the grotesque racist enterprise of the Raj and the other colonial “estates,” the unified nation conjured in the latest Brexit fantasies and Victorian era imperial propaganda.

But then many have long been thoroughly unconvinced by these adverts of national greatness, refusing the imagery and cultural imaginary of colonial pasts, rejecting the seductive certainties of postcolonial melancholia. This process has to be seen as a vital, invigorating counterpoint to the economic and political machinery at the cultural and material core of our colonial inheritances. Ultimately, the Britain which is promised renewed unity, sovereignty, freedom and supremacy in the thoroughly compromised idea of Brexit denies the Britain of Nazneen depicted in Monica Ali’s Brick Lane and Samad Iqbal in Zadie Smith’s White Teeth; spoken about in Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan’s This is not a Humanising Poem, Benjamin Zephaniah’s Dear White Fella or Novelist’s Stop Killing the Mandem. It negates the depth and discomfort of Riz Ahmed’s Englistan – a new drama telling the story of three generations of a British Pakistani family as they pursue their dreams over four tumultuous decades. It cowers from the more difficult effort at what historian Catherine Hall calls “reparatory history,” where history reading and writing (and I would add listening and seeing) can illuminate present moral and ethical concerns. Especially important when the new economic (the aegis of racial neoliberalism), socio-political (the uncertainties of “race”), and most important, ecological dislocations and configurations of our time, with the startling realities of human interdependence on a world scale, make the situation all the more complicated. There is a need for a denationalised imagination and exilic narratives which ‘stretch’ the fabric of culture to house us all.

Let me be clear. This is decidedly not a call for the feeble, often bureaucratised efforts at ‘diversity’ or ‘multiculturalism’, those buzzwords of the Left, which further entrench a fragile and anxious status quo. It is instead an escape from the status of victimhood which, we must remember, is central to the neo-fascist resurgence on the European political scene. It is a break with “good conscience” and is a decentring force which challenges, if not altogether encourages, abandoning the certitude and comfort of speaking from the ‘centre’. The measure of any society is the material access to dignified life denied to those at the receiving end of brittle definitions of community, all too often derived from racialized notions of the ‘centre’. We are not solely in the realm of abstract art or entertainment or debate. All the above is inextricably tied to responsibility and to justice.

If nations are narrations, concerted acts and processes of storytelling, of remembering and being remembered, then it is these voices which offer more capacious images of the nation, insisting that the story of Britain must be open to multiplicity in its authorship. The American poet, Lucille Clifton, says it well in why some people be mad at me sometimes:

they ask me to remember

but they want me to remember

their memories

and i keep on remembering

mine.

We, the threats to the West, must continue to insist on remembering our memories for they open us all up to the possibility of sensing, thinking, acting more expansively, more compassionately. To recognise the messiness, ambiguity, horror, hope, tragedy, and brevity of being in the world, in spite of those who’d have us amnesiac and afraid. Ultimately, the image of the restored Supermarine Spitfire must sit alongside the noble and the ignoble; the routine beauty of melting-pot-inner-city tower block life, while remembering the systemic crime of Grenfell; the hijab-wearing star and winner of The Great British Bake Off, Nadiya Hussain, yet cognizance of the reality of structural, often gendered Islamophobia and Islamophobic violence; the sense of coherence and rootedness in the union jack, with all the atrocities committed in its name.

References:

Bouteldja, H. (2016) The Whites, The Jews and Us. South Pasadena: Semiotext(e).

Gilroy, P. (2006) After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture. London: Routledge.

Hall, C. (2018) ‘Doing reparatory history: bringing ‘race’ and slavery home’ Race & Class, 60(1): pp.3-21.

Mackenzie, J. (1984) Propaganda and Empire: The manipulation of British public opinion, 1880-1960. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Said, E. (1994) Culture and Imperialism. London: Vintage.

Muneeb Hafiz is a PhD Candidate and Associate Lecturer at Lancaster University, UK. Building on Achille Mbembe’s work on race and Blackness he explores: (i) the effects of the modern/colonial encounter between ideas of race, raciology and (popular) culture; and (ii) the contemporary impacts of colonial politics and imperial processes of racialization in the context of Islamophobia in Britain. He completed his MA at Lancaster University where his dissertation was on UK counterterrorism policy and the political philosophy of Hannah Arendt.

IMAGE CREDIT: Late 19th century McVitie and Price advert of the Queens Dominions and its products