Chin Ting-Fang

Recently, the already heated debate about same sex marriage equality has reached a new peak in Taiwan. On the one hand, legalization has never been so close. On 26 December 2016, a legislative committee approved the preliminary amendment of the legal proposals of marriage equality. It is an historical step that had never been achieved before. On the other, the anti-gay voice in this society is busy articulating its dissent. The opponents are relating their concerns and fear through rhetoric of religion and Confucianism.

Taiwan is therefore in a leading position to be the first country in Asia to legalize same-sex marriage. The result of the 2016 election has brought Taiwan the very first President who has publicly endorsed same-sex marriage during her presidential campaign, President Tsai Ing-Wen [蔡英文]. In addition, her party, the Democratic Progress Party (DPP) has won the majority seats in the Legislative Yuan. Several DPP candidates for the legislature declared their intention to champion marriage equality during the election campaign. This has won them support from the LGBT community and young voters. Now these voters are waiting to see this political promise fulfilled.

It has been a long process for marriage equality to be seen as a ‘proper’ and urgent issue for politicians to address. Most of the credit should go to the activists and supporters who have been agitating for legal reform. The LGBTQ movement in Taiwan has stayed strong since it’s flourishing in the 1990s. The growing annual Taiwan Pride serves as good example to illustrate the vibrant and diverse LBGTQ scene here. General discussion about same-sex marriage emerged around 2000. The more organized movement to push legalization of same-sex marriage was launched in 2012 when the Taiwan Alliance of to Promote Civil Partnership Rights [TAPCPR; 台灣伴侶權益推動聯盟] proposed Duo Yuan Cheng Jia Legal Draft [多元成家草案; The Diversification of Family Legal Draft]. ‘Duo yuan’ [多元] means ‘diversity’. ‘Cheng jia’ [成家] means ‘to have a family’ or ‘to establish a family’. The draft covered three different formations of familial relationships. The first is same-sex marriage. The second is civil partnership. The third is multi-person familial partnership. From both the title and the content of the draft, it is revealed that the ultimate goal is not just to legalize same-sex marriage but also to rewrite the legal definitions of family and familial relationships. Although there was never an opportunity for this radical draft to be discussed by legislators, it has successfully raised the public awareness of the movement and drew the political parties’ attention.

In late 2016, the first legislation session under Tsai’s Administration was held. It was also the very first session in which three bills regarding marriage equality were reviewed by legislators. Each bill was proposed by a different political party. With slight differences in design, all versions share the common ground of revising Article 972 of the Civil Code. Article 972 states that ‘an agreement to marry shall be made by the male and the female parties in their own concord [sic].’ It is proposed that the gendered wording, ‘the male and the female parties’, should be changed to a gender-neutral terminology in order to legalize same-sex marriage.

The mainstream media coverage of marriage equality has been partially contributed to by the severe backlash from anti-marriage equality groups. Among them, churches appear to take a leadership role. They expressed their heteronormative concerns in the name of the well being of the next generation in the context of the general prosperity of society. From their perspective, to legalize same-sex marriage would totally destroy the so-called ‘traditional family value, social ethics and the meaning of life’. In their arguments against marriage equality, the conventional heterosexual marriage is constructed as a holy shrine of traditional social order, which has never been changed and cannot be changed. A mixed (or remixed) rhetoric of conservative Christianity and Confucianism is emerging from their arguments. Some of the religious representatives and their followers even adopted a liberal tone to claim that they ‘respect gay people’ but same-sex marriage can never be written into the Civil Code. However, this is not to say that all the religious groups have come hand in hand to sing a harmonized tune together. In fact, there has been steady pro-marriage equality support from organizations and individuals with religious background, such as the female Buddhist master, Shih Chao-Hui [釋昭慧]Shih Chao-Hui, Pastor Chen Si-Hao [陳思豪], and Tong-Kwang Light House Presbyterian Church [同光同志長老教會].

Unfortunately, since her inauguration, Tsai’s Administration and her party have shown an ambivalent attitude to this matter. Some legislators broke their promises and withdrew their support. There is even a suggestion to propose a special act on same-sex civil partnership, rather than support the Civil Code amendment on marriage equality. This indecisive stance is regarded as a sign of compromise from both sides and therefore provides fuel to the already intense confrontation in the civil society. On 17 November 2016, when the Judiciary and Organic Laws and Status Committee were reviewing the proposals on same-sex marriage, there were both pro-marriage equality and against-marriage equality allies outside Legislative Yuan.

This political context is crucial for understanding the supporters’ reasoning on the legal reform of familial relationships. In my pilot study on marriage equality in Taiwan, I interviewed supporters of the campaign about the reasoning behind their stance. While it is a political reality that other proposals for the diversification of the legal definition of family were not available in time, it is suggested by my research data that the alternative imagination about family relationships is not being forgotten. My participants’ accounts reveal the complexities around this issue. Take the accounts by Chih-Lu, for example, she does not value the system marriage over that of civil partnership in general. For her, the more options the better:

Ting-Fang: You support same-sex marriage, right?

Chih-Lu: Yes.

Ting-Fang: How about civil partnership?

Chih-Lu: Mmm… By civil partnership, do you mean it is the only option or it can co-exit with same-sex marriage? […] I just want to make sure that when you asked me if I supported same-sex marriage or not… Let’s put it this way to make it simpler. That is, I support the more options the better. I support the idea that in a certain time and space, same-sex marriage and [same-sex] civil partnership are both available. If it is a time and space in which only one option is available, then I don’t support [same-sex] civil partnership.

Chih-Lu is against the system of same-sex civil partnership because it would be discriminating against same-sex couples. She is aware of that the current political situation has left no space for a legal framework of civil partnership for all individuals.

The Legislative Yuan is currently in recess and the rallies on the street have dispersed for now. However, the debate is still going on in Taiwanese society. The anti-marriage equality groups continue spreading counter-arguments with their homophobic anxiety, particularly through social networking services, and the supporters of the legal reform feel the need to undertake action. There are more and more campaign activities organized by self-motivated individuals. The activities tend to be local and small-scale with the aim of reaching out to members of the public who, at the moment, do not care about or understand the issue. Some created fact-check lists to refute the false and discriminative information about LGBTQ communities, such as the absurd linkage between being gay and infected with HIV. Some designed stickers and badges for supporters to proclaim their stance on the matter in their everyday life. Others organized events to reach out and build up local networks. Others still developed guidelines to persuade elder family members to support marriage equality at the Lunar New Year Eve dinner. This civil revolution is happening not only in the meeting rooms of the Legislative Yuan, but indeed, also on the streets and around the dinner table.

Chin Ting-Fang recently completed her PhD in the Centre for Women’s Studies at the University of York. Her PhD thesis explores women’s experience of gender at work in Taiwan with a focus on everyday practices. She is currently engaging in research on marriage equality in Taiwan.

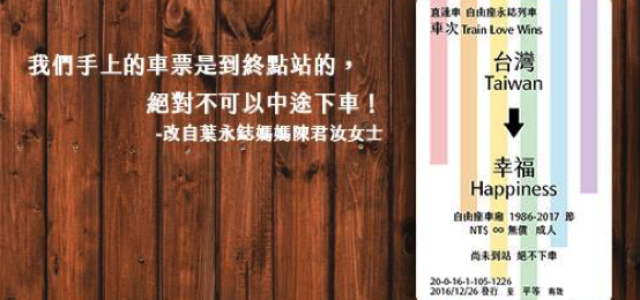

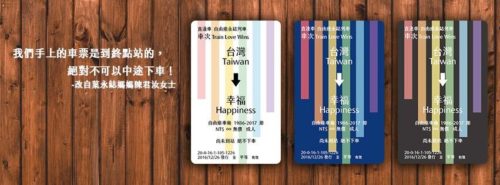

Image Credit: The design sample of stickers by Shen Che-Yu [沈哲宇]. He is the creator of the Taiwan to Happiness Sticker Project.

The photo shows the design sample of stickers promoting marriage equality. On the left is a sentence in Mandarin which means ‘the ticket on your hands is for the final destination, and we shall never alight midway’. This slogan is inspired by and paraphrased from the public talk by Ms. Chen Chun-Ju [陳君汝] at the 2016 Kaohsiung LGBT Pride. Ms. Chen has been an important figure for gender equality and LGBTQ rights after the tragic death of her son, Yeh Yung-Chih [葉永鋕], a victim of gender discrimination. On the right, there are three sticker samples in different colours. The stickers are formatted as railway tickets to echo the talk by Ms. Chen. The details are designed with implications about marriage equality. For example, they are marked as tickets for general admission, which in Taiwan are called the tickets for zih you zuo [自由座]. The Mandarin term could be interpreted as ‘a seat of freedom’.