Steve Garner and Somia Bibi

Skin-lightening is a multibillion dollar industry that reinforces racialized inequality for profit. Beginning with a British Academy Small Grant we are attempting to ‘sociologise’ skin-lightening practices in England. We have commenced by trying to establish a base-line, using anonymous surveys, about what people buy and how they use products.

While there are sociological, cultural, and marketing studies on other areas (particularly West-Africa, the Caribbean, USA and some Asian sites), there is currently no published work specifically about skin-lightening in England, apart from some short medical articles. Indeed, the first thing to note is that medical, sociological and cultural studies literatures exist in parallel and disconnected worlds. Moreover, there is more television and print journalism on skin-lightening in the UK than published sociological research.

Skin-lightening has a long history, however, we are currently in a specific conjuncture, where important ways of understanding the social world come into conflict. Namely the power of neoliberal ideas about the individual (consumer, rational actor, ‘self-responsibilized’ agent) versus the collective patterns expressed through this ostensibly individual consumer choice: paler skin is more sought-after.

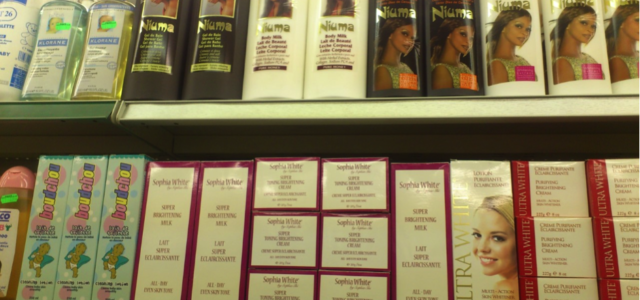

The annual generation of tens of billions of dollars via skin-lightening, is not an accident: it reflects companies’ focus on women’s appearance, and the message that paler complexions increase chances of better employment, spouses/partners, and living conditions. The racism of which colourism is a subset, and which is expressed in this way, ensures a continually flourishing market. Furthermore, university researchers are engaged in the pursuit of skin-lightening products that are more effective, i.e. that efficiently hinder the body’s production of melanin. These are products that require repeated use. The full weight of international capitalism, its marketing efforts and dominant ideas about choice, thus falls directly upon women of colour, pushing some to use products that are illegal and unhealthy (e.g. that contain poisonous substances like lead and mercury). At the same time, little heed is given to the dangers of melanin suppression in the proliferating legal and presumed safe/healthy alternatives.

From our preliminary findings (using a sample of 114) 42 different brands and 93 products have been identified, with the cheapest product being £1.45 to the most expensive products being £45 (only attainable via Spas) – products were primarily creams and soaps. Products used varied from non-permanent mechanisms like foundation several shades lighter than skin-tone, to the long term application of creams. Our research thus suggests that the conceptualization of what constitutes a ‘skin-lightener’ may need to be broadened to include products like foundation and BB creams.

In our sample, the starting age for skin-lightening usage is concentrated in the 16-24 range. Multiple avenues of sourcing products were identified; the high street, online EU/non-EU based companies and purchasing abroad. However, products were mostly acquired in local shops (54% of respondents). 66% of respondents used products on a daily basis, suggesting skin-lighteners are a part of many people’s daily beauty regimes, with many products also promising to take care of skin more broadly, by for example ‘moisturizing’ and ‘softening’, and/or ‘brightening’ skin. Both legal and illegal products were identified.

The distinction between legal and illegal (according to the existing EU regulations) is policed only by resource-limited trading standards officers; although products containing mercury or hydroquinone are illegal, they can be bought online or brought back from overseas trips. Indeed, one of the products cited by some respondents in our research has recently been found to contain mercury, and thus removed from local shops in Birmingham, but is readily available online. Trading Standards is constrained by the illegal/legal distinction, while Public Health organisations can only react to observable patterns of harm. Yet it is worth noting that the ‘healthy’/ ‘unhealthy’ binary does not map directly on to the legal/illegal one (which is subject to legislation and can therefore change). While many deleterious outcomes of skin-lightening use are medically identified, suppression of melanin per se, even using ingredients that are currently legal, seems likely to reduce the skin’s capacity to protect the body against skin cancer induced through UV rays.

Even this is to focus on the physical without even talking about the potential psychological damages asserted by Christopher Charles (2011, 2007), for example. Indeed, one of the readings of skin-lightening practices is that of self-harm. However, blaming people for using the products is probably not the way to change practices drawn down from a broader racist culture which attributes greater value to paler skin, and in which sustained attempts to make skin ‘brighter’ are made intelligible.

It is clear that skin-lightening is an everyday practice in England, one that requires investigation. It is also a set of complex practices irreducible to a simple reading that states that the practitioners desire whiteness. Firstly, that must be one element, but why, how and under what conditions? Secondly, there is a need to ensure that one does not become trapped in binary dynamics of white and black. The issue is a multi-dimensional one which evolves and manifests differently across/within socio-cultural environments and communities of colour. A sociology of skin-lightening should eschew an exclusively micro-focus on the users, just as it should also engage with users, rather than merely produce secondary analyses. Aiming to understand processes, it should see a political economy and an emotional economy embedded in one another. Skin-lightening is a raced and gendered practice, but alongside the women (and men) buying the products, its practitioners include those in the boardrooms of large corporations; marketers; and researchers in laboratories.

References:

Charles, D.A.C (2007) ‘Skin Bleachers; Representations of Skin Color in Jamaica.’ Journal of Black Studies, Volume 40, Number 2, pp. 153-170.

Charles, D.A.C (2011) ‘The Derogatory Representations of the Skin Bleaching Products Sold in Harlem.’ The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 117-141.

Steve Garner is professor and head of criminology and sociology at Birmingham City. Somia Bibi is a PhD student at Warwick University.