Rosalind Edwards, Val Gillies and Nicola Horsley

Families have long been regarded as signalling and determining the state of nation, so it is seen as important to collect information about the ones that pose problems. Offers of assistance to disadvantaged families have been accompanied by acts of investigating and recording details about them. But the information collected is not neutral, not merely descriptive records of fact. The Troubled Families Programme, with its emphasis on specific eligibility criteria and family monitoring data, is the latest in a history of codifications of disadvantaged families and their difficulties seen as requiring particular interventions that reflect the pervasive concerns of the time, and that create their own verification.

Reviewing the instruments of systematic data gathering over time provides insights into shifts in these social and political preoccupations, and helps us to assess future directions. The material collected in case notes about disadvantaged families by the Family Action agency, with a history stretching back to its foundation in 1869 as The Charity Organisation Society (COS), shows that there’s been a move away from a concern with identifying and labelling eligibility and deservingness to assessing and measuring risk and an accompanying shift from a spotlight on parents to a focus on the perceived needs of children.

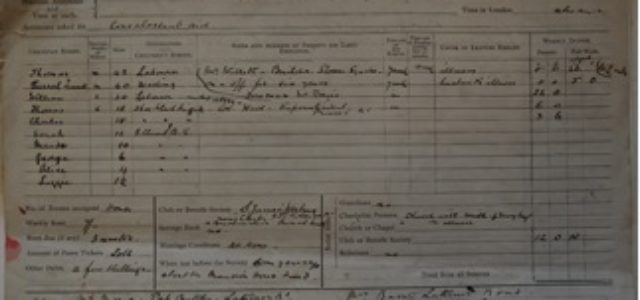

In its pioneering casework approach in the late 19th century, the COS pursued investigation into the circumstances of those approaching the agency seeking charitable relief. The information gathered in a handwritten ledger allowed COS to identify whether or not the applicant met its criteria for assistance. The ledger included details about the applicant and family members, records of their employment, income, rent and debts, the nature of their application for relief, and whether or not other sources of support (relations, savings clubs) were available. Importantly character references were obtained from landlords, employers, clergy, and other people defined as upstanding. In other words, the information was concerned with establishing eligibility through calibre of character and deservingness of charitable relief. This can be placed in the context of widespread assumptions that family deprivation was a result of parental immoral character, and a preoccupation with easy access to charitable relief discouraging self-reliance and thrift.

By the 1930s such moral certainty had become subject to challenge, and parents were regarded as amendable to, rather than undermined by, help with problems. For families that approached COS to ask for support ideas about character are echoed in the form of questions about armed service during the Great World War. Details about insurance provision through societies, unions and clubs were also collected. References were still obtained, augmented by the case officer’s handwritten observations about respectability, responsibility and appearance of both persons and home. While poor families were still regarded as authors of their own misfortune, in the aftermath of the Great War concerns focused on improving the physical and mental state of the nation’s stock.

The focus on the psychological state of applicants developed into the post World War II period, as well as a concern with ‘problem families’. COS re-named itself the Family Welfare Association (FWA) and specialised in casework and therapeutic interventions into the emotional dynamics of families referred to it as in need. By the 1970s psychoanalytic ideas were embedded across a range of statutory and voluntary services, including the Family Services Units, which were eventually amalgamated with the FWA. This preoccupation resulted in detailed typed case notes analysing the personality and history of family members, including ‘repeated patterns’ of relationships intergenerationally, along with a listing of the family’s financial and other circumstances, and contacts with other welfare agencies. This period saw a fixation with ‘cycles of deprivation’ where disadvantage was posed as transmitted between generations in families.

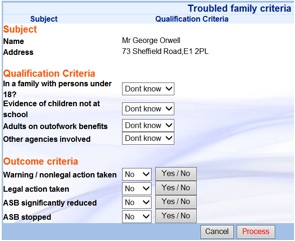

Attention to the minutiae of parenting practices has intensified in more recent times. As part of services delivered under the Troubled Families programme – now called Family Action, which structures its case data around an ‘index child’ whose welfare is judged to be significantly at risk and in need of intervention. There has been an exponential increase in the amount of information required in line with the mandatory Common Assessment Framework, along with the use of standardised tracking tools to continually assess children’s developmental needs, parenting capacity, and family and environmental factors, as well as a tick box record of parental characteristics and circumstances, and a risk assessment. These sets of information can be collected digitally and in many cases saved directly onto the relevant local authority’s central recording system. The focus on poor parenting – seen as at the root of societal problems – as well as a child protection agenda are clearly reflected in the instruments of measurement and classification.

Alongside the shifts from preoccupations with eligibility and deservingness to assessing and measuring risk, and from a concern with parents to a focus on children’s needs, we can also trace another trajectory. This moves from a reliance on evidence via references from authority figures, but in response to a family’s self-identified need and request for support, through to an increase in professional judgements and the referral of families for intervention in relation to professionally-defined need, to the channelling of professional assessment into tick boxes and the administrative dictation of family needs.

With a change in technologies from handwritten and typed analogue information towards digital linked administrative data, many are anticipating a possible turn towards less information being collected from/about families directly and less exercise of professional judgement, heralded by the uploading of details about families into a central database. The perspectives of parents and children in disadvantaged families, and of the judgements of the professionals who intervene in their lives, can be managed out of the system to be replaced by the spurious objectivity of quantified administrative facts that, under a National Impact Plan, can link their case data to other administrative data held on them by public agencies.

Technologies of e-government offer the potential to define new possibilities for the classification and measurement of disadvantaged families. In particular, the preoccupation with and ability to link to biological data held on family members may shape new types of intervention. A policing of the poor through, and authoritarian co-opting of, surveillance biotechnologies looms on the horizon.

Rosalind Edwards is Professor of Sociology at the University of Southampton. Val Gillies is Visiting Professor at Goldsmiths, University of London. Nicola Horsley is a Research Associate at the University of Loughborough. This article is based on the ‘Troubled Families’ and Inter-Agency Collaboration: Lessons from Historical Comparative Analysis’ project carried out in collaboration with Family Action and funded by the ESRC under its Secondary Data Analysis Initiative: ES/L01453X/1. Case files of families with dependent children were selected and analysed from four periods of economic recession: the Long Depression (1873–1896), Great Depression (1930–1934), Oil Crisis (1973–1975) and Global Financial Crisis (2008–2012). The research team also produced an interactive timeline of their history for, which can be accessed on their website.

Image: Case note front page from (The Charity Organisation Society 1896 (London Metropolitan Archives). Below: Troubled Families Programme online data collection programme 2014 (Hubsolutions).