Michael Shea

For almost a decade the political discourse in the UK and beyond has been dominated by the rhetoric of austerity. It would be difficult to count the number of times we’ve each heard phrases like “belt-tightening,” “do more with less” and “live within our means” out of the mouths of politicians and journalists.

We have all heard the policies of the UK government justified as follows: “everyone knows if you max out your credit, you don’t go out and get another one!” or words to that effect. This explanation is based on the fallacy that national and household debt are in some sense analogous. There are various reasons why this comparison is absurd. Most households do not have the power to issue bonds, raise money through taxation or own a controlling stake in a national bank to name a few.

These phrases demonstrate a carefully selected use of language intended to create the sense not only that the policy of cutting public services is not only a necessity but that any alternative would be morally repugnant, the “tyrant’s plea.” The credit card analogy is designed to appeal to the listener’s sense of personal financial responsibility.

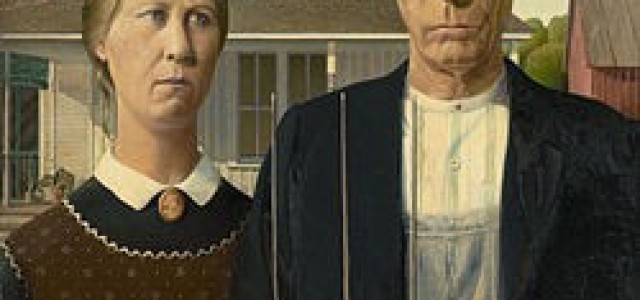

The image of the reckless individual who maxes out their credit card and fails to learn their lesson, immediately getting another one conjures up an archetypical image of profligacy. The speaker might as well tell the fable of the Ant and the Grasshopper to make their point. The nauseating, often repeated soundbite “should have fixed the roof while the sun is shining” to refer to the Labour party’s time in office, is deployed to similar effect.

For example, consider the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s 2015 budget speech: “in normal economic times governments should run an overall budget surplus, so our country is better prepared for whatever storms lie ahead. In short we should always fix the roof while the sun is shining.” In the same speech, the Chancellor describes how the budget measures will allow us to “live within our means as a country,” using language which is intentionally both vague and preachy.

The use of morally-weighted rhetoric to justify economic behaviour is nothing new. Max Weber, one of the founding figures in sociology, famously made the case in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism that the development of capitalism in Northern Europe had been profoundly influenced by the Protestant values of prudence and frugality, sometimes referred to as the “Protestant work ethic.”

This spirit of capitalism does not refer to the spirit in the metaphysical sense, but rather a set of values, the spirit of hard work, of progress, that were historically associated with Protestantism. However, it is important to not that, even in Weber’s view, these values are not specific to any one religion. He argues that this spirit emerges wherever traditional forms of capitalism based on interpersonal relationships have been replaced by the rationalized organization of labor.

To exemplify this attitude, Weber quotes several passages from Advice to a Young Tradesmen, a 1748 essay by Benjamin Franklin: “Remember, that time is money. He that can earn ten shillings a day by his labor, and goes abroad, or sits idle, one half of that day, though he spends but six pence during his diversion or idleness, ought not to reckon that the only expense; he has really spent, or rather thrown away, five shillings besides.”

A less well known quote from the same essay highlights the often blurred distinction between ethical and economic notions of prudence and frugality: “The most trifling actions that affect a man’s credit are to be regarded. The sound of your hammer at five in the morning, or nine at night, heard by a creditor, makes him easy six months longer; but, if he sees you at a billiard table, or hears your voice at a tavern, when you should be at work, he sends for his money the next day, demands it, before he can receive it, in a lump.”

In this view capitalism was believed to embody moral justice, like an invisible hand of God, rewarding those who work hard and save money and punishing those who don’t. This rational but false belief in the karmic value of financial turmoil still underpins how many people view economic crises, which is why the deployment of morally weighted, if not religious, language by politicians is still so powerful.

The politics of austerity can be debated endlessly and it is not my intention to argue that a consensus could easily be established. Nor is it my intention to argue that religion and morality have no place in political or economic discussions. Far from it. It is precisely because the ethical value of fiscal prudence is so widely held that morally-weighted language is still such an effective rhetorical tool when making economic arguments.

It is important to interrogate the choice of words by politicians on all sides, particularly when they are used to silence opposition as morally unacceptable or to distort the public’s understanding of a complex issue. We must be wary each time an individual defers to the rhetoric of austerity rather than considering how the policy works in practice.

Michael Shea is a freelance writer and researcher based in the United Kingdom. He studied Social Anthropology at the School of Oriental and African Studies before completing a PhD in Material Culture at University College London. His work addresses various issues regarding culture, media and design. [https://twitter.com/0michaelshea]

Image: American Gothic by Grant Wood (Art Institute Chicago)