Nicoletta Fagiolo (Independent Researcher)

Photo: A non-violent and unarmed sit-in to block the security forces from breaking up an Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) Congress, 30 April 2015, Mama, Côte d’Ivoire.

“The Igbo people say,

If you want to see it well, you must not stand in one place.

The masquerade is moving through this big arena.

Dancing.

If you’re rooted to a spot, you miss a lot of the grace.

So you keep moving, and this is the way I think the world’s stories should be told;

from many different perspectives.”

Chinua Achebe

“The History of my country is too recent Madame President, and those who try to falsify it by twisting its neck are engaged in an exercise which is unlikely to succeed. Madame President, as I do not want to be the shame of my generation and I refuse to be thrown into the dustbin of History, I would like to bring some freshness to the collective memory that those I call fact smugglers are trying to erase.”

With these words in October 2014, Ivorian youth leader Charles Blé Goudé, known since 2002 as ‘the street General’, for his ability to mobilize large numbers of people onto the streets for huge non-violent protest marches, addressed the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) pre-trial hearing. Charles Blé Goudé is facing a joint trial for crimes against humanity at the ICC with former Ivorian President Laurent Gbagbo. Yet, for many Ivorians, Blé Goudé is their hero for being a non-violent youth leader who managed in all crucial moments of the country’s recent history to block an illegitimate takeover of the government by a foreign backed rebellion, the Forces Nouvelles (New Forces).

For a large part of the Ivorian population, Laurent Gbagbo, ‘deported’ to the Hague, embodies the country’s democratic nationalist interests in a post-colonial state which had to face neo-colonial practices of western imperialism, including the use of political memory as propaganda. So as to legitimize its coercive ways, western mainstream media, NGOs and major think tanks, as well as many academic and “expert” historical publications, conveniently omit the 2002 rebel incursion and falsely depict the Ivorian crisis as an ethnic civil war or a war between a Muslim north against a Christian south. Why? And for whom? For a western audience whose consensus on the use of force is needed to accomplish coercive foreign policy actions?

Former President Laurent Gbagbo, a socialist, historian and the father of Ivorian democracy, has a personal history of over 40 years of non-violent struggle. This is a key factor in understanding the country’s recent crisis

Demonstration for the liberation of Laurent Gbagbo from the ICC, Paris, June 2013. The photo is of Gbagbo when arrested back in 1988 fighting the one-party dictatorship with non-violent means.

in relation to the Forces Nouvelles. President LaurentGbagbo was on a state visit in Rome when, on the 19 September 2002, the Forces Nouvelles rebels crossed the border from Burkina Faso and launched an attack on major cities, including the southern coastal metropolis and commercial capital Abidjan. The Interior Minister Émile Boga Doudou, as well as the former President General Robert Guéï, among others, were assassinated. Gbagbo asked the French to intervene to help push back the rebels by acting on the Franco-Ivorian 1961 Defence agreement. France refused, opting instead to create a buffer zone between the north and the south, a policy choice which ended up de facto splitting the country in two for years to come.

Blé Goudé’s youth movement embodies one of the most extraordinary examples of non-violent resistance when faced with extreme violence such as that exercised by the French Licorne force in the Bouaké events of 2004 which, by shooting at Ivorian demonstrators a mains nues (unarmed), saw the death of 67 people and injuring over one thousand. Sixty French tanks had come to surround President Gbgbo’s residence on the 7 of November 2004 saying they had “lost their way” as they were trying to reach their official destination, the Hôtel Ivoire. Many people, fearing a French coup attempt, came onto the streets and remained singing out into the night. Former French Ambassador at the time Gildas Le Lidec justified the French shooting at unarmed civilians crossing a bridge to reach a French military base as the only way to halt another “battle of Dien Bien Phu.”

The Forces Nouvelles rebel occupation had devastating consequences for the northern region under their control: one million people fled to the south, many others into exile, the state services became defunct in their area, as a parallel tax system emerged. In 2009, as the 2010 elections were approaching, the UN were still calling the region under rebel control a “warlord economy”. A large part of these ex nihilo rebels were foreign mercenaries and their bright new uniforms and readily available cash were signs of substantial financial backing. The disarmament of Forces Nouvelles was called for at all eight peace accords leading up to the 2010 elections, but was never achieved.

Following the 2010 contested election between incumbent President Gbagbo and Alassane Ouattara, Gbagbo, as early as December 2010, was calling for a supervised recount of the votes. The brief reports from news agencies worldwide, however, repeated only one story: Gbagbo lost the elections in November 2010, but was reportedly clinging to power. It is this version, although contested by a wide range of recently published evidence, which prevails in many accounts of this period.

The Central, North and West regions (known as CNO) remained under rebel control until 17 March 2011 when Alassane Ouattara appointed them as the national military force, renaming them the Republican Forces of Côte d’Ivoire (FRCI). By not acknowledging this rebel coup d’état an armed takeover was legitimized.

During the post-election crisis, the Ivorian state television (RTI) signal was blurred and, in mid-March 2011, French Canal + Afrique Horizon officially discontinued RTI from its digital satellite bouquet, not allowing the news from Côte d’Ivoire to be viewed in neighbouring African countries, or in France. Yet people communicated via Skype, Facebook, mobile phones and alternative and social media sites to receive first hand news directly from those on the ground. Africans living outside of Côte d’Ivoire discovered on a daily basis that what was happening on the ground was not what was reported on French and other foreign news outlets, the schism was so great that it bewildered many.

How did such diverse versions of the country’s recent history come to coexist? Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Nigerian diplomat during the crisis and scholar, Ademola Araoye, in Côte d’Ivoire, writes that France, through RFI (Radio France International) and numerous other print and electronic news outlets, has determined and interpreted the facts of the Ivorian crisis to the world (1). Journalist Théophile Kouamouo quit his job with French newspaper Le Monde in 2002 as the editorial staff in Paris changed the content of his articles, distorting what he wrote to fit the ideological line pushed by the French Foreign Ministry. Kouamouo, who is Franco-Cameroonian, went on to found his own daily Ivorian news outlet and wrote J’accuse Ouattara among other books (2).

A demonization campaign had been unleashed against Laurent Gbagbo the year he came to power with a film, La Poudrière Identitaire (Explosive identity) where he is depicted as an ethnocentric dictator fomenting exclusionary identity politics. Nothing could be further from the truth. Gbgabo’s government of “professors” in 2000 was the most multi-ethnic Côte d’Ivoire has ever had and his reading of nationality went beyond ethnic or tribal affiliations, to include a strong state and an innovative decentralized administration that could guarantee citizenship rights across the board. In 2006, he and his wife Simone Gbagbo won a defamation suit against French newspaper Le Monde which was condemned by the Paris Court of Appeal for saying the Presidential couple had used “death squads”, an accusation demonstrated to be unfounded. A more recent documentary film Shadow Work, published on the internet under the title “How Laurent Gbagbo ruled with an Iron Fist” depicts Charles Blé Goudé as a violent militia leader targeting foreigners; missing out on history, the film in the voice-over confuses events and facts with opinions and even falsifies the English subtitles to fit a faulty narrative. These reductionist visions stick to this day in mainstream French media and beyond.

The country’s former colonial power was also seen as legitimizing the rebellion through diplomatic coercion. Soon after France’s entry into the mediation of the conflict, the rebels broadened their demands to include political concessions and, at the French-brokered Marcoussis peace accords in January 2003, the Gbagbo government was asked to include rebels in its government. The military intervention, which ended the four month post election crisis with the 10 day bombing of the Presidential palace in April 2011 to oust Gbagbo was condemned at the time by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov at the UN Security Council as a regime change policy. Lavrov argued that the UN and France had no right, according to the UN resolution, to take sides in the conflict.

Jean Ping, former Chairperson of the Commission of the African Union, felt powerless in 2011 as in both the Libyan and Ivorian crisis, the African Union mediation, which had opted for a non-belligerent resolution of the crisis, was swept aside. Ping recalls that year as a watershed for traditional diplomacy: “we had no one in front of us to count on, no countervailing power, which is essential for democratic governance. Global governance, which has become de facto unipolar has fallen from the hands of the P5, G8 and G20 to a P3 transformed into a G3, who appeared absolute, boundless, with no checks and balances, facing the G0 that we represented” (3). Thabo Mbeki, South African mediator in the crisis – from 2002 to 2006 and again in 2010 – wrote an article at the height of the crisis in April 2011 in Foreign Policy, ‘What the World Got Wrong in Côte D’Ivoire’, yet his cry fell on deaf ears.

If the “G3” (France, England and the United States) is the new geostrategic paradigm shift of world politics then it needs a narrative to legitimize it: the ICC, acting as lawfare, becomes a tool through which to further legitimize a faulty narrative. Some law scholars have already coined the ICC as “Europe’s Guantanamo Bay”. The de-contextualization of history is one of the key elements that the Gbagbo defence team deplored during the pre-trial hearing. The timeframe chosen at the ICC to address the Ivorian crisis, which focuses on the post-election crisis (thus excluding the rebel attack of 2002-2010) as well as refusing to look into how the elections were conducted, is ludicrous. These factors hugely discredit the ICC in the eyes of former Italian ambassador to Côte d’Ivoire, Paolo Sannella, who was an eyewitness to the devastating consequences on the country of an externally funded rebel occupation.

On 3 June 2013 the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber issued, by majority, a decision where it found that all the incidents and four main charges did not meet the evidence threshold at the pre-trial level to go to trial. Yet, instead of freeing Gbagbo, the Court decided to adjourn the hearing and requested that the Prosecutor “consider providing, to the extent possible, further evidence or conducting further investigation”. “A grotesque juridical decision”, according to Gbagbo’s lawyer Emmanuel Altit, “as an adjournment should not be called for all incidents and charges mentioned in the DCC. Yet it shows that we managed to prove at the pre-trial hearings that the charges are unfounded” (4). This decision was then reversed a year later, yet the dissenting Judge Christine Van den Wyngaert’s opinion still calls for a halt in the legal proceeding to commit Gbagbo to trial, due to lack of evidence for all the accusations brought against him.

Recently, multiple narratives – such as an Ibgo masquerade dance making use of critical memory – have been put forward questioning the dominant narrative. Also, Franco-Cameroonian investigative journalist, Charles Onana, through first-hand interviews with the principal actors of the crisis, government and multilateral sources, intelligence reports, leaked correspondence, and more, traces a journey through historical archives uncovering new facts about what is at stake in the region (5). Unfortunately, the substantial new evidence that these publications have disclosed is ignored in subsequent accounts.

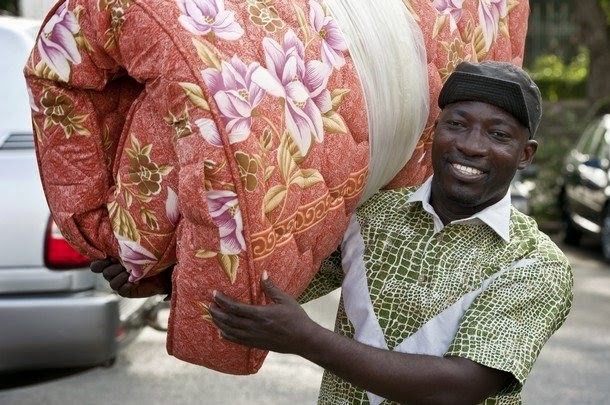

Charles Blé Goudé, the leader of Pan African Congress of Young Patriots (COJEP) holding a two day prayer sit in with a mattress calling for a peaceful resolution of the crisis on 25 of March 2011, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire as the rebels were advancing from the North.

Held in detention since 2011 at the International Criminal Court, but still very popular amongst Ivorians, Gbagbo was recently re-elected president of his party, the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) in April 2015. A few days later, the current Alassane Ouattara regime responded again, as it has done in the past four years, through brutal force and violence, by arresting on May 4 2015 three of the FPI’s leaders who have joined the country’s circa 1,000 political prisoners. Today a wide coalition is forming against the growing authoritarianism, insecurity and risks of a failing state under Alassane Ouattara.

On a weekly basis, since April 2011, the Ivorian resistance worldwide holds demonstrations and marches for the liberation of Laurent Gbagbo; trips to the Hague are also frequent. Recently, thousands gathered for Gbago’s 70th birthday on 31 May 2015, holding talks, dancing and singing in front of the prison. They demand justice and an acknowledgement of the memory of the many victims of the Forces Nouvelles rebellion since 2002 that are excluded from most current history books, as well as being unrepresented amongst the victims at the ICC.

Which history will this future generation of Africans read when seeking to understand their past and their present? Can a politicized memory distort a collective identity formed through shared lived experiences? How should one define a historical exercise which ignores new emerging evidence and multiple voices? A large part of these “truncated” accounts may become redundant, their striking elisions standing as proof of insufficient documentation and critical memory. Chinua Achebe lamented the reductionist vision of Joseph Conrad’s use of animal imagery to depict Africans in Heart of Darkness: “He didn’t see anything wrong with it. So we must live in different worlds. Until these two worlds come together we will have a lot of trouble.”

References:

(1) Ademola Araoye, in Côte d’Ivoire, The Conundrum of a Still Wretched of the Earth, Trenton, New Jersey, Africa World Press, 2012.

(2) Théophile Kouamouo, J’accuse Ouattara: Pourquoi la place de cet homme est devant un juge,Paris, Le Gri Gri, 2012.

(3) Jean Ping, Eclipse sur l’Afrique, Fallait-il-tuer Kadhafi? Michalon Editeur, Paris, 2014. p. 157

(4) Nicoletta Fagiolo, Interview with ICC Defence Lawyer Emanuel Altit, May 2015 Paris, France.

(5) Charles Onana, Côte d’Ivoire, le coup d’Etat (2011) e France-Côte d’Ivoire, la Rupture (2013), Paris, éditions Duboiris.

Nicoletta Fagiolo is a journalist and documentary filmmaker. She graduated in Contemporary History at La Sapienza University in Rome, Italy and went on to study International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She worked for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as well as humanitarian evaluation officer for the Italian Foreign Ministry. Since 2005 she writes and directs reportages and documentary films for Aljazeera international, RAI SAT, France 2 among others. In 2009 she wrote and directed Résistants du 9ème Art (Rebels of the 9th Art), a documentary film on African editorial cartoonists fighting on the frontline for freedom of expression and is currently working on a documentary film Laurent Gbagbo, the right to difference.