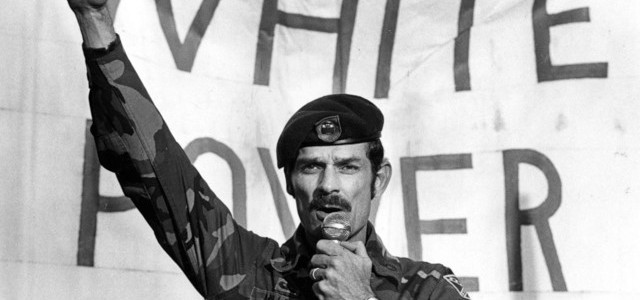

Image: Frazier Glenn Miller

Aaron Winter (UEL)

Much recent discussion has focused on the rise of what has been termed the far- and/or extreme-right across Europe and America. In Europe, it is populist, anti-EU and anti-immigrant parties that made gains in recent national and European elections, such as the Front National, Danish People’s Party, Golden Dawn and UKIP, as well as racist, anti-immigrant and Islamophobic protest groups. In America, discussion has focused on armed confrontations and violent incidents such as the Bundy Ranch stand-off in Nevada in March 2014, the April 2014 shootings at a Jewish Community Centre and retirement home in Kansas by former Klansman Frazier Glenn Miller and the June 2014 shootings in Las Vegas by anti-Government activists Jerad and Amanda Miller.

Such developments were warned about by the US Department of Homeland Security (USDHS), Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), Political Research Associates (PRA) and Anti-Defamation League (ADL). The 2009 USDHS report Rightwing Extremism: Current Economic and Political Climate Fueling Resurgence in Radicalization and Recruitment argued that the election of an African-American President and economic downturn provided the conditions for a resurgence of right-wing extremism not seen since the 1990s, which, with its anti-government movements, government sieges and terrorism, could be repeated. The 2009 SPLC report, The Second Wave: Return of the Militias, also saw the potential for a revival of anti-government activism from the 1990s and violence. More recently, the SPLC has argued that the Bundy stand-off can be seen as the event around which the anti-government extreme-right coalesces and mobilises, much as Ruby Ridge and Waco were in the 1990s.

Yet, this has little to do with parties and developments in Europe where the anti-EU, anti-immigrant and Islamophobic parties and protest groups being discussed are to the right of, but overlap with, mainstream ideologies and parties. None of these American anti-government paramilitaries, neo-Nazis and white separatists are running for office, appealing to the state or engaging with the mainstream, instead they are taking up arms, engaging in violence and calling for race war and revolution. It is for these reasons that I label the former ‘far-right’ and the latter ‘extreme-right’. While the Tea Party can be seen as far-right in European terms based on its anti-federalism and anti-immigrant xenophobia, as well as suspected racism and Islamophobia, it is a wing of an established party fighting for hegemony within it.

Groups like Golden Dawn occupy both positions – far-right electoral and extreme-right street activism using violence. But with a few exceptions, such as former Klansman David Duke who ran for state and national elections in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, and even won a seat in the Louisiana House in 1989, there have been no significant extreme-right candidates since Civil Rights and no party post-war. Frazier Glenn Miller ran for office in the 1980s and 2000s, but was an unsuccessful fringe candidate.

In order to understand the rise of the extreme-right in the US, and particularly the convergence of racism and anti-government ideology occurring today (and largely directed at Obama), we must return not only to the 1990s as USDHS suggests, but also to the post-civil rights 1970s/1980s when the extreme-right moved from traditional system supportive activism to the paramiltarism and anti-government activism that peaked in the 1990s. With few exceptions, the American extreme-right, dominated historically by the Ku Klux Klan, had been system-supportive. Its members defended racist laws, lobbied congress, ran for office and supported racist and anti-communist politicians. Violence was committed, but in conjunction with electoral activism, in defence of laws and under the protection of law enforcement. According to the Ku Klux Kreed from the 1950s: “We, THE ORDER of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan [….] RECOGNISE our relation to the Government of the United States of America […]and we shall be ever devoted to the sublime principles of a pure Americanism and valiant in the defense of its ideals and institutions.”(1)

The passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and Voting Rights Act in 1965, as well as an FBI investigation into the group and House Un-American Activities hearings Activities Of Ku Klux Klan Organizations in the United States from 1965-1967 which declared them ‘un-American’, (2) were seen by the Klan to represent the loss of white supremacy that they had defended and their persecution by the federal government. In response, the group retreated to the political wilderness and underwent a split. While much attention focused on David Duke’s electoral campaigns and the so-called ‘mainstreaming’ of the Klan, he was an exception. The Klan was ‘mainstream’ in the context of legal white supremacy, and many of Duke’s fellow Klansmen would go on to reject the mainstream for the margins following Civil Rights.

From 1969 through the 1970s, more radical Klansmen established new Christian Identity affiliated anti-government and anti-Semitic Patriot, neo-Nazi and white separatist groups, such as Posse Comitatus and Aryan Nations in California and the mountainous geographical margins of the Pacific Northwest. The late 1970s and early 1980s saw Klansmen trading in their robes and burning crosses for fatigues and guns, and forming paramilitary units such as Miller’s White Patriot Party and Louis Beam’s Texas Emergency Reserve. These groups rejected political engagement for armed insurgency and revolution. In the words of Beam, who joined Aryan Nations, ‘where ballots fail, bullets will prevail’. (3) They also rejected white supremacy and defensive nationalism for white separatism. Beam’s statement from the 1980s stood in stark contrast to the Klan’s Kreed: ‘Political, economic, religious, and ethnic conditions in the United States have reached the point where patriots are faced with a choice of rebellion or departure.’ (4)

These anti-government groups expanded throughout the farm crisis of the 1980s. Anti-government activism increased again in the early 1990s, filling the post-cold war vacuum. In this context, the racist, anti-Semitic and anti-government Patriots of the 1980s would be joined by the less race-based militia movement which emerged in response to Ruby Ridge. The bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on 19 April 1995 by Timothy McVeigh, who claimed it was revenge for Waco, would bring the extreme-right to national and international headlines. In response, five Senate sub-committee hearings were held: Combating Domestic Terrorism, The Militia Movement in the United States, The Nature and Threat of Violent Anti-Government Groups in America.The Federal Raid on Ruby Ridge, ID., The Activities of Federal Law Enforcement Agencies Toward the Branch Davidians. The latter two acknowledged the role of government actions in extremism and violence, something that was not done following 9/11 or in relation to US foreign policy. Soon after, many of the groups that dominated the period went into decline because of lawsuits, prosecutions, aging leadership and irrelevance.

9/11 provided what many saw as an opportunity for relevance. While the mainstream right was calling for patriotism and national unity, National Alliance, Aryan Nations and others saw a movement that also hated America, Israel and Jews. In response, they issued statements of congratulations and calls for alliances. (5) The National Alliance’s Billy Roper claimed ‘The enemy of our enemy is, for now at least, our friend’. Aryan Nations’ August Kreis posted ‘Why Islam Is Our Ally’ and created the position of Minister of Islamic Liaison (6).This stands in contrast to the Islamophobia of European far-right parties, as well as more militant activists such as the EDL and Britain First and violent ones such as Anders Breivik, and went relatively unnoticed by both the American government and al Qaeda.

As USDHS warned, the election of an African-American President and recession would provide conditions for the right-wing extremism, and, I would add, a convergence of racism and anti-government ideology.Jerald O’Brien of Aryan Nations called Obama the ‘greatest recruiting tool ever’, while Jeff Schoep of the National Socialist Movement argued that a combination of race, the economy, immigration and anger at the government was contributing to movement growth. According to the SPLC, between 2000 and 2013, the number of hate groups rose from 602 to over 1000, growth that can be attributed to Obama’s election and the economy. In 2008, prior to Obama’s election, there were 149 anti-government Patriot groups. This number jumped to 512 in 2009 and rose to 1,360 in 2012, an all-time high that dropped slightly in 2013. Between 2009 and 2014, there have also been 17 shootings involving anti-government extremists. According to a July 2014 report by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, US law enforcement views the anti-government Sovereign Citizen movement as the top terrorist threat. While Europe is experiencing a rise in xenophobic anti-immigrant parties, America has seen a decline in more militant and extremist nativist groups since 2010, but an increasing acceptability of anti-immigrant ideology in mainstream Republican circles.

Because of the higher number of anti-government groups and spectre of the militia dominated 1990s, the focus has been on anti-government activism as opposed to racism. This ignores the relationship between racism and anti-government activism that developed from the 1970s, but is in line with historical state approaches to extremism. Even in the Klan hearings in the 1960s, violence, criminality and being ‘un-American’ were the focus. While the reasons for this in the 1960s may have had to do with separating the Klan from the mainstream and the legal racism they supported and defended, and focusing attention away from it as both racism and the Klan were being exorcised from the body politic.

In the current context, it may be that America has constructed a post-race discourse where racism is not frequently acknowledged and accusations of racism are viewed as tantamount to racism. It may also be that it allows the government to focus on the political-national aspect of the activism and allows critics of the right to make the link between the extreme-right and more extreme elements on the right through overlapping anti-government ideology. This is something conservatives have criticised about the USDHS report, thus making the link themselves. In spite of concern and debate about overlap between different sectors of the right, the focus of the USDHS report and much analysis of violent incidents has been the so-called ‘lone wolf’. This is a perpetrator who, by definition, removes any affiliation with or responsibility from any movement, organisation, nationality, religion or race, an option that Muslims do not get.

Where does the extreme-right in the US stand now? While we are seeing an increase or cluster in high profile violent incidents, according to the SPLC, the number of anti-government groups is dropping slightly. The picture is also mixed in the mainstream where the Tea Party is given last rites every time a candidate is defeated and revived when another wins. As for the implications of this for Europe, the American extreme-right and Tea Party are focused on domestic affairs and while they both appear ready for a second American Revolution, it has little to do with Britain and its far-right, nor with the far-right in the rest of Europe.

References:

1. Ku Klux Klan (1952) ‘The Ku Klux Kreed’, The American Klansman, Jan. p. 14.

2. US Government (1966) Activities Of Ku Klux Klan Organizations In The United States, Hearings before the Committee On Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-Ninth Congress, 1965-66; (1967) The Present-Day Ku Klux Klan Movement, Hearings before the Committee On Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Ninetieth Congress, 11 Dec.

3. James Ridgeway (1990) Blood in the Face: The Ku Klux Klan, Aryan Nations, Nazi Skinheads, and the Rise of the New White Culture, New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, p. 87.

4. Louis Beam Jr. (1987) ‘Seditious Conspiracy’, Calling Our Nation, n. 58, p. 21.

5. George Michael (2007) The Enemy of My Enemy: The Alarming Convergence of Militant Islam and the Extreme Right, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press; Aaron Winter (2014) ‘My Enemies Must Be Friends: The American Extreme Right, Conspiracy Theory, Islam and the Middle East’, Conspiracy Theories in the Middle East and the United States: A Comparative Approach, eds, M. Reinkowski and M. Butter, Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 35-58.

6. Martin Durham (2007) White Rage: The extreme-right and American politics, London: Routledge. p. 79.

Aaron Winter is Senior Lecturer in Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of East London. His research is on organised racism, right-wing extremism, hate crime and terrorism. He is co-editor of Discourses and Practices of Terrorism: Interrogating Terror (Routledge, 2010) and Reflexivity in Criminological Research Experiences with the Powerful and the Powerless (Palgrave, in press), and has contributed to Religion and Violence: An Encyclopedia of Faith and Conflict (M. E. Sharpe, 2010) and Extremism in America (University Press Florida, 2013). He is co-convenor of the British Sociological Association Race and Ethnicity Study Group and a member of the editorial board of Sociological Research Online.