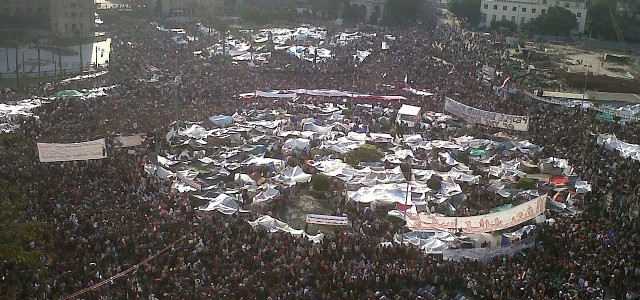

Image: Tahrir Square, 2011

Noor-ul-Ain Khawaja and Muhammad Hashsham Khan, University of Westminster

The former army chief, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, has won the Egyptian Presidential election, becoming the third President since 2012. His only rival, the leftist politician Hamdeen Sabahi, got a mere 3 percent of the votes. The turnout, at 46 per cent, was much lower than the elections that had brought the previously elected President, Mohamed Morsi, to power in June 2012.

Egypt has been experiencing political transformation since 2011 with the end of the three-decade long military regime of Hosni Mubarak. The establishment of a democratic system in 2012 opened a new chapter in Egypt’s history. The Muslim Brotherhood also acquired a powerful position for the first time in its history with the election of Mohamed Morsi as President. But this democratic change did not last longer than a year.

The former head of the military, Abdel Fatteh Sisi, overthrew Morsi’s government and imposed an interim government with the head of the Supreme Constitutional Council, Adly Mansour, appointed as President. New elections were called, but the Muslim Brotherhood was banned from contesting them and was declared a terrorist organization. Hundreds of its activists were sentenced to death, the first mass death sentences in the history of the country, and thousands of Muslim Brotherhood activists and leaders, including Morsi, have been held awaiting trial.

The election of Sisi – who is supported by the Supreme Constitutional Council (SCC) and the Supreme Council for Armed Forces (SCAF), as well as the Islamist Al-Nour party, the biggest Salafist party – suggests at least a temporary cessation of the crises and opposition encountered by Morsi.

After Mubarak

After the resignation of President Mubarak in 2011, the Supreme Council for Armed Forces (SCAF) assumed power and introduced constitutional reforms, which had already been promised by Mubarak, through an eight-member committee. Key political actors raised their voices against the reforms primarily because the committee members were appointed by SCAF itself and SCAF had not deposed the judges appointed by Mubarak. Instead, the judges were granted more powers. The Supreme Constitutional Council (SCC) was also empowered to dismiss, or declare as ineligible, members of the People’s Assembly (Lower House) and to supervise the election process.

Before the election of President Morsi, SCAF, in consultation with the SCC, had issued an addendum, which sought to enhance the judiciary’s role, along with its own, and to weaken the role of the President. The following reforms were made:

- The High Constitutional Court (HCC) was empowered to take oaths from the President in the absence of Parliament.

- SCAF secured powers to appoint its own members and their terms and extensions.

- Without SCAF’s approval the President could neither declare war, nor could call armed forces to maintain peace and stability.

Hence, SCAF gained significant powers, ranging from legislation to the state budget to the appointment of civilian and military employees and political representatives.

The scenario demonstrated that an atmosphere of mistrust between the institutions already existed before the new government assumed power. The reforms also suggested that the military was not ready to provide space for the new system.

The constitutional crisis took another twist when the SCC exercised its powers to dissolve the People’s Assembly just two days ahead of the Presidential elections. The dissolution of an Islamist majority parliament was a significant and challenging event. Setting aside the Political Exclusion Law, the SCC allowed the former Prime Minister of Mubarak’s regime, Ahmed Shafiq, to run for the Presidential elections.

SCAF supported the action and claimed that, ‘if any part of the Parliament is illegal, then the entire body should be dissolved.’ This mutual understanding between the SCC and SCAF was considered a great challenge to the new Morsi government.

Morsi’s Constitutional Measures

After winning the elections and assuming power, President Morsi realized that without strengthening his position he would not be able to make independent decisions. As a result, he took a series of measures to strengthen the role of the President.

He dismissed the head of SCAF, Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, who was also Defence Minister, and the Chief of Army, Sami Anan. But in order to secure his ties with the military, he appointed them as his advisers and awarded them with State Medals. The opposition, however, demanded that the generals should be put on trial for brutal violence against demonstrators during the post-Mubarak period and many considered Morsi’s decision as a provision of safe exit for the generals.

Morsi appointed a new prosecutor-general which invited the anger of the judiciary. He also cancelled SCAF’s proposed addendum (above) which challenged the authority of both SCAF and the SCC. As a consequence, the President regained all legislative and extra executive powers, which had been bestowed on the President through the 1971 Constitution.

The Shura Council was authorized to establish a Constituent Assembly to draft a constitution. The SCC was deprived of reviewing the President’s powers and of dissolving the Constituent Assembly. The Islamic Al-Azhar University was empowered with more consultative authority; military courts were given authority to conduct civilian trials; and there was a ban on the National Democratic Party (NDP), which was considered an attack on pro-Mubarak officials.

The unilateral announcement of this decree on 22 November 2012 inflamed the situation. It was condemned by all sections of society and triggered mass protests throughout the country. The opposition argued that Morsi’s move entailed the promotion of theocracy and the undermining of secular and liberal political sentiments. The military finally intervened to overthrow the Morsi government in July 2013.

Political outlook

The present state of affairs with Sisi appears to be different. The latter is a very strong candidate with an influential military background. In contrast, Morsi was a weak candidate with little prior political experience. In fact, at the beginning of the uprising in 2011, the Muslim Brotherhood adopted an apolitical stand. Mohamed Morsi, at that time, was the group’s media officer and had stated, ‘We want to participate, not to dominate’. The Muslim Brotherhood changed its agenda in May 2011, registered its political party, the Freedom and Justice Party, to contest elections. Its support for SCAF’s constitutional amendments immediately created a division within the party, with influential reformist leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood, such as Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, leaving it.

SCAF was seeking a weak Presidential candidate through which it might avoid judicial trial for its mishandling of protesters during the interim period. So, it chose the inexperienced Morsi, instead of more influential candidates.

Nevertheless, when Morsi assumed power, he neither addressed opposition demands, nor strengthened ties with his major ally, Al-Nour. The growing momentum of the protesters throughout the country pushed the country into turmoil. Despite Morsi’s rejection of SCAF’s 48-hours ultimatum, even Morsi’s Republican Guards did not resist when he was arrested.

Sisi enjoys the favour of the Gulf states. With the exception of Qatar, the overthrow of Morsi’s government was hailed by them. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE announced an aid package of 12 billion dollars in total to sustain the interim political order. Morsi’s open support for Hamas and restoration of ties with Iran after 30 years had triggered suspicion among the West and the Gulf states respectively.

Egypt is the second largest US aid recipient country, annually receiving 1.3 billion dollars in aid and over 50 per cent of its exports go to the US and Europe. Morsi did not seek to strengthen ties with the US which is one reason why he lost the West’s support. The US condemned the overthrow of Morsi’s government by the military, but avoided calling the action a coup, when, according to the US law, they would have to freeze all aid.

Egypt’s military runs the major enterprises in the country, roughly estimated at 40 per cent of the Egyptian economy. This estimation makes the situation potentially more favourable for Sisi and his military tycoons, but with some clear risks.

Morsi’s government could not be held responsible for economic failure, as his government had inherited a weak and failing economy. The director of emerging markets at Roubini Global Economics, Rachel Ziemba, has stated that, ‘the seeds for Egypt’s economic troubles were planted by Mubarak’. In addition, Mubarak’s government borrowed heavily to finance stimulus packages during the worldwide economic downturn, leaving Morsi to pick up the tab. Sisi will have to deal with tough economic challenges.

In the present circumstances, the new constitutional Charter has enhanced the role of the military. The assumption of power by Sisi represents a return to the status quo, as a former military head will once again become head of the state. However, Sisi will need to redefine his intention towards the 85-year old Muslim Brotherhood. He has said he would finish it off if he came to power. But it has deep roots – not only within the country, but in the whole Gulf region. Any coercive action against it may backfire and plunge the country into a civil war. Low turn-out in the election should put Sisi on notice that he does not enjoy the support of a large portion of population.

Noor-ul-Ain Khawaja is currently pursuing an MSc degree in the Department of International Relations, University of Karachi, Pakistan. She was previously Senior Research Officer and in charge of the Research Department, at the Pakistan Institute of International Affairs. Muhammad Hashsham Khan is currently pursuing an MA in International Relations, University of Westminster. He has recently held a four-month internship at the Pakistan Institute of International Affairs.