Les Back (Goldsmiths) and Shamser Sinha (University Campus Suffolk) [pdf]

Christian’s mobile phone vibrated as he settled into his seat for the flight to Croatia. Two weeks ago the UK Border Agency (UKBA) informed him that he no longer had leave to remain in Britain and asked him to provide flight details of when he planned to leave the country. On Facebook, he informed his friends in Croatia that he was coming home. Before turning his phone off for the flight, Christian looked down and checked a new text message. To his surprise it was from UKBA. It read: “have a pleasant journey.” The politeness of the British Immigration Officials that had questioned and scrutinized him was somehow the hardest thing to take.

Christian’s story is emblematic of the new realities of border control. Their technologies are as mobile as the migrants. In a hyper-connected world, the regulation of movement is more complex and technologically sophisticated. It is not just that migrants face institutionalised forms of marginalisation – without leave to remain they cannot work or have recourse to public funds – they also have to live with a sense of insecurity enhanced by the mobile phone in the palm of their hands.

In 2010, it was estimated that there were 214 million international migrants in the world, representing an increase of almost 40 million in the first decade of the 21st century. One in three of these migrants is a young adult. The regulation of youth migration is producing new hierarchies of exclusion and belonging that order and rank the life chances of this globally mobile generation.

It is not only that young people are moving but that the border is also moving and being multiplied. While it continues to exist at the edges of the EU and UK, internal immigration controls now proliferate everywhere – from the lecture theatre to the workplace, the crèche and the rental landlord – filtering by immigration status who can move through what spaces. The practices required to police differential inclusion move into communities and neighbourhoods.

It is a common observation that the relationship between time and space is radically transformed through technologies like jet planes, smart phones and the Internet. The connected nature of our world goes hand in hand with the proliferation of bordering practices. These no longer only happen at Heathrow or Calais when we fumble for the passport in our bags. Rather, border control is being ‘in-sourced’. Landlords, doctors, health visitors, teachers, University lecturers are all being asked to pass on information, through monitoring student attendance or documenting home visits. Willingly or not, they are enlisted as affiliates of immigration control.

Border policing is also being contracted out and privatised. In September 2012, the services company Capita won a contract from the British government to find and remove the estimated 174,000 migrants who have overstayed their visas. So it is not quite accurate to say that Christian’s text came from UKBA; the texts are sent from a private company on its behalf.

This year the controversy about the Home Office ‘Go Home or Face Arrest’ van campaign raised public concern about the damage done to Britain’s cosmopolitan cities. The campaign invited overstayers to text ‘Home on 7870” and the Home Office used Twitter to offer a running commentary on the van campaign. Anti-immigrant racism and xenophobia is given official public license in both off line and on-line worlds.

Theresa May, champion of the new Immigration Bill, says the government is set on “making it harder for people who are here illegally to stay here”. But these crackdowns are targeting people who have done nothing wrong. Capita’s text message campaign is resulting in people being wrongly told to leave the country.

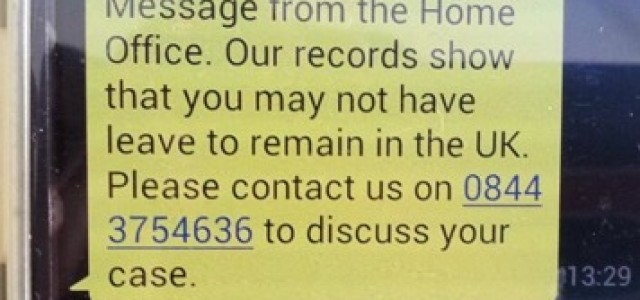

In September 2013 Suresh Grover received a text that read, “Message from the Home Office. Our records show that you may not have leave to remain in the UK. Please contact us to discuss your case” <<Article amended 19/10, 2013 to provide correction of message text sent to Suresh Grover. Others received the text attributed to him: “Message from the UK Border Agency, You are required to leave the UK as you no longer have the right to remain.” >> Suresh is a leading civil rights activist and founder of the Southall Monitoring Group, which was involved in campaigns for justice for the families of Stephen Lawrence, Zahid Mubarek and Victoria Climbie.

On the 12th September, Suresh Grover submitted a request to UKBA under the Freedom of Information Act (FOI) 2000 for an explanation as to why he had received the text. The response from UK BA is revealing. It said Capita is provided with a “regular data drop” containing information on people including mobile phone numbers who have a “negative outcome” on the Home Office immigration database”. It claimed that Capita had contacted 39,100 individuals by text, while acknowledging that this figure is “provisional and subject to change”. The numbers are almost certainly much higher.

The response said nothing about how they had obtained Suresh Grover’s mobile number. Rather it just stated that when an error is identified records are “immediately up dated and contact is ceased.” It also claimed that in a “very small number of instances” where their records relate to a “different person and this has only transpired during the contact process e.g. where a mobile phone number has changed hands.” Suresh is not alone. There are other cases where UK passport holders have received similar texts including an immigration advisor.

The FOI response from UKBA contained no explanation of how the mobile phone number of one of Britain’s leading civil rights activists found its way into the ‘data drop’ provided to Capita by the Home Office. No apologies are being made – either from Government or UKBA – for the potential damage that results from invasive e-border control of this kind.

Britain’s immigration system has often been referred to as Orwellian. These cases reinforce the idea that through our mobile phones “Big Brother” is watching. Although, Orwell’s state-controlled dystopia is not quite what is emerging. Ours is an out-sourced and privatised neo-liberal dystopia. We should have deep reservations about the social costs of entrusting an important issue like the implementation of migration policy to a private company that is making damaging mistakes.

Aggressive anti-migrant campaigns do little to face the issues raised by the fact that the human family is now more mobile than at any other point in history. The politics of scapegoating and blame targets whole communities and not just the ‘bad individual’ who are here illegally as is disingenuously claimed. The history of racism teaches us this lesson.

The mobile phone is now an instrument of border control, but it is also a connecting device. Salle, as a child in in Tirana, Albania, was obsessed with telephones. He pulled old telephones out of the rubbish bins and took them to pieces only to re-assemble them again like little telecommunication Frankensteins. His obsession with phones was in part due to the fact that the telephone was his link to his older brother who would call home every month or so with news of his life in London. Today he is still obsessed with phones but now it is with mobile ones.

In 1999 as a result of the Serbian persecutions 7,500 Kosovans fled into Albania and guns were circulating in Tirana. Salle’s parents were relatively well-off by Albanian standards – his mother was a nurse and his father worked as a Forest Ranger. A kidnap economy developed where relatively well off children were held to ransom. Salle was afraid and his brother paid £4,000 to a pair of smugglers – a man and couple posing as a family – to secure Salle’s passage to London. His route through Europe is a remarkable story and he eventually got himself into the back of a truck full of beer and was picked up by the Kent police. He was twelve years old.

He lived with his brother in Barking and ended up in a school in Dagenham in Greater London. Salle only found a footing when he met Harbhajan, a builder and a non-religious Sikh with left-wing leanings: ‘All the people in the building trade hate the Eastern Europeans but I love ‘em.’ His building firm is made up of Rastafarian painters and decorators, Polish labourers and Albanian plumbers. Salle’s fortunes changed when he connected with Harbhajan’s business which itself was built on a kind of multicultural labour market in a sector of the economy that is fraught with racism and resentment.

Salle’s immigration status is now stable and, unlike many, he can move freely around the world and return to London without fear of being held or deported. He works mainly repairing and restoring the properties of London’s super rich and middle class. His mobile phone is his way to stay connected to his family in Tirana, his multi-ethnic networks in London, and the young Albanians who arrange to meet via text message every Friday night at a pub in east London.

Successive British governments have claimed that the UK ‘points-based immigration’ system arbitrates on the basis of what young people can do rather than who are they are. This is little more than an ideological gloss concealing the thick lines being drawn within a generation of globally mobile young people. Here the terms of inclusion are set by where you are from, how much money is in your bank account, and whether or not you will be granted leave to remain as a result. The border itself moves, nets, captures and expels unwanted or unneeded people. This becomes visible chillingly when Christian receives a text message from UKBA: ‘have a pleasant journey’.

Les Back is Professor of Sociology at Goldsmiths University of London. Shamser Sinha is Senior Lecturer in Sociology and Youth Studies in the School of Applied Social Sciences, University Campus Suffolk. They are writing a book based on their joint research project, Migrant City, to be published by Routledge in 2015.