Solveiga Zibaite

During my recent personal explorations on what’s new in the gaming world, I came across something strangely relevant to my academic interests: a game called A Mortician’s Tale, released on 18th October 2017 by a Canadian indie company Laundry Bear Games, and marketed as ‘narrative-driven death positive video game’. Death in video games is often presented as a minor nuisance, followed by respawning (a gaming term meaning that after dying, the character is brought back into the game; a contrasting concept is permadeath where the death of a unique character is permanent), and engaging with death in a profound and instructive way is a fairly new development. Further Google searches produced a plethora of sensational headlines, such as: ‘A Mortician’s Tale might be the first game to really get death’, ‘Indie game dares to talk about death in a way few others have’. The user reviews on A Mortician’s Tale’s Steam shop page, however, had a completely different tone.

I was intrigued by the dissonance between the manufacturer’s claims and the feedback of the users. I realized this has something to tell us about the polarized understandings surrounding the contemporary death positivity movement. A look at A Mortician’s Tale as a video game, supposedly aligned with the goals of the death positivity movement, will serve well to highlight the inconsistencies. I will also discuss several other games that have succeeded in engaging with death positivity, because A Mortician’s Tale is not the first of its kind, despite appearing that way in the media.

The death positive movement is a contemporary proliferation of bloggers, artists, funeral directors, entrepreneurs, educators, death workers and other people connecting and speaking openly about death, dying and bereavement. Order of Good Death website is a good introduction to the movement. The majority of death positivity tenets on the website stress the importance of accessible self-education resources, building a competent vocabulary on issues surrounding death and acknowledging the presence of death, as well as exploring one’s fears and discontents. A significant problem is the term ‘death positivity’ is sometimes used by the public and content creators in ways that are not consistent with the movement’s mission. In part of articles, reviews, comments, etc. on the topic, death positivity is understood as having positive feelings towards death. Ideas about death positivity are perpetuated in a way that confuses, and limits, the amount of people who might want to identify with the movement.

Games that engage with death positivity precede A Mortician’s Tale and are increasing in number. In ‘The Graveyard’, developed by Tale of Tales in 2008, the player controls an elderly woman walking slowly through a graveyard towards a bench, all in grayscale and without a soundtrack, just birds chirping and dogs barking. The controls require patience – if you make her walk too fast she begins limping; her frailty is almost tangible. As she sits on the bench during a moment of introspection, a Dutch song about cleaning graves of unknown people plays. The song concludes with – Next time, perhaps I will stay here. Then you get up and exit the graveyard. Buying the full version provides the same gameplay except there is an added possibility for her to die at any moment. Introducing the possibility to die provides a well-developed death positive idea that death is a part of the human experience.

Another heart-wrenching example is That Dragon, Cancer, created by parents to honour and memorialize their terminally ill son. There is no winning objective; rather, it is an intimate look into the everyday attempts to make sense of their lot: cherishing precious moments of togetherness, drowning in helplessness of anticipatory grief, attending to an inconsolable child and other aspects of their experience. It’s a brave project in its vulnerability, as much about loss as it is about hope and exploring grief, the struggling mechanics of which help to convey the inability to have control over any outcome, whether in game or in life. In both of these games, the gameplay is a vehicle for enabling introspection and communication about mortality and grief. This is consistent with the goals of the death positivity movement.

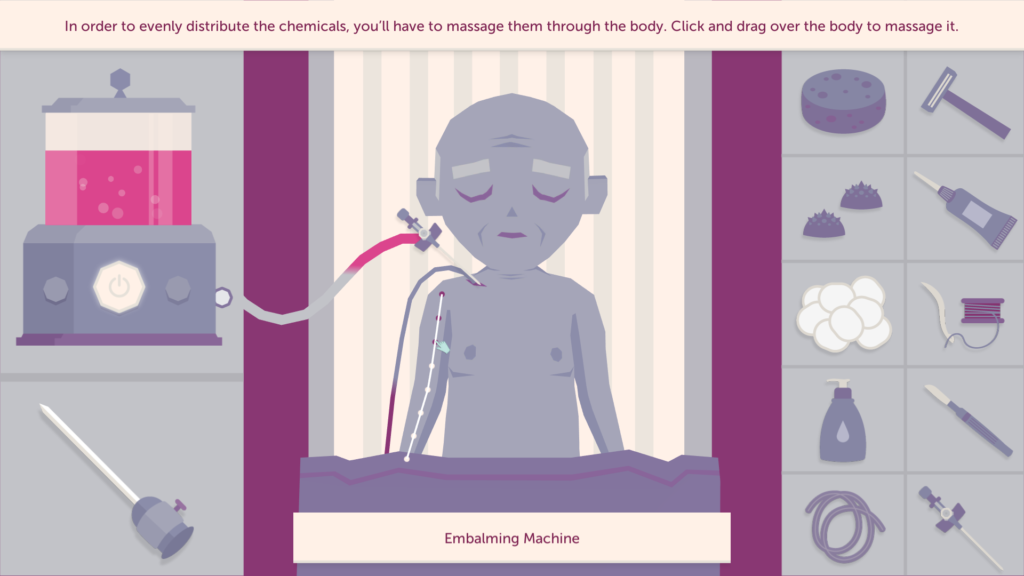

In A Mortician’s Tale, one plays as a recent mortuary science graduate who joins a family-run funeral business. In its short gameplay (around one hour) she prepares (washes, embalms, cremates) eight bodies with different backstories for viewings and deals with emails. The game has a feeling of a long tutorial, the player is guided very diligently through repetitive actions of embalming, interacting with the mourners only through listening to their conversations and is not allowed to fail. You read an email, there’s no option to respond, you prepare the presented body, attend a wake, repeat- all with a click of a mouse. The colour scheme mostly consists of various shades of pastel purples, characters’ bodily proportions are slightly exaggerated, and the soundtrack contributes to the aura of reverent concentration.

A selection of interviews with the designer of A Mortician’s Tale, Gabby DaRienzo reveals a discord with the mission of the death positivity movement, despite being inspired by it. She states that although containing leakage from various orifices is a pretty big part of corpse management and [they] wanted to be as accurate as [they] can, but this might be the thing that crosses the line (emphasis mine)]. She also states that she doesn’t want it to come across as a horror game (ibid). Because in A Mortician’s Tale, death is reduced to pastel colour scheme and cartoon-like corpses, the horrors of decomposition or disfigurement would be hard to depict anyway, but, if necessary, liquids are not hard to desensitize – blue menstruation liquid has been employed successfully in marketing. However, here only presentable liquids – those in sealed containers, not unbounded human bodies – are allowed.

In this game we meet Baudrillard’s simulacra at work. In the absence of real experiences of death in contemporary Western society, we simulate them. The simulation of death in A Mortician’s Tale has to be sterilised to be ‘digestible’. The simulation masks the reality, goes further – masks the absence of reality and eventually replaces the reality. The fact that this is perceived by the game’s creator and reviewers as ‘accurate’, or even breaking the taboo surrounding death, illustrates how far removed death is from everyday life.

DaRienzo also remarks that human heads are made bigger to ‘break any kind of uncanny valley vibes’. Uncanny valley theory suggests that the viewer’s affinity towards a humanoid object steadily increases as its resemblance to a human grows, until it dips significantly when the entity begins to appear eerily, but not quite human. This uncanniness subconsciously elicits fear and repulsion. Because A Mortician’s Tale seeks to portray the realities of death and death work, the concern with uncanniness and the revulsion players would supposedly experience if the game characters were extremely human-like should not be relevant. The death positivity movement promotes acknowledging death as a part of our shared human experience, thus it would never be considered foreign or revolting. This game is a double simulacra then – one of death and one of a dead human being. In the same interview DaRienzo states: ‘it’s really important for us to find the correct amount of accuracy versus comfort. It’s very different to read about a thing, and imagine it, and directly interact with a dead body, like you are right now. If clicking on a twice-removed cousin of a corpse on a screen is perceived as problematic, it signals that death in our society remains an extremely uncomfortable topic, but this supposed death positive game does not challenge it in any significant way.

The death positivity movement encourages self-education on death, but A Mortician’s Tale marginally fulfils this goal. It provides interesting facts in emails, such as different cultural customs around death, initiatives and innovations, such as Death Cafes, alkaline hydrolysis, etc. It also introduces embalming to the completely unaware, but I would argue that the game’s full potential might be reached by reworking it for children, and the visuals wouldn’t even have to be changed. Removing the subject of suicide and the storyline of corporate evil might make for a short non-frightening explanation on what happened to granddad.

Because anyone can contribute to the collective knowledge of the internet by sharing their opinions, it is hard for the death positivity movement to maintain an authoritative voice, image and ensure a clear understanding of its goals. A Mortician’s Tale is at most a lacklustre attempt to create a death positive video game. For its success, it relies on the largely young and digitally native demographics of the death positivity movement. This, combined with the game’s extensive marketing as a brave novelty, makes for an assertive yet misguided product. We should perhaps remain critical about the cultural output being produced under the umbrella of death positivity. What I see here is a careful selection and partial appropriation of the movement’s mission, akin to assembling a pick’n’mix in a candy store.

Solveiga Zibaite is a PhD student in the School of Interdisciplinary studies at the University of Glasgow. Her research interests include anthropology of death, online ethnography, anthropology of cyberspace, online memorial cultures.

Pictures from A Mortician’s Tale, Presskit (permission to use acquired)