Sait Bayrakdar

You only need to switch on the television or radio to listen to the latest discussions around the so-called EU-Turkey deal, designed to stem the flow of migrants from East to West to appreciate that migration is certainly one of the hottest topics of our time. Whilst media coverage is designed on one level to make us better informed of the facts, figures and arguments around migration, it is often both anecdotal and speculative, leaving the general public with perceptions that are one-dimensional, missing large parts of the story, lacking in the most important thing – hard evidence.

Few people would disagree that it is in everyone’s interests that we better understand the motivations of migrants and what difference migrating makes to their lives. How to do that effectively is a matter of concern not only to academic and social researchers, but to policy makers and society as a whole.

Also given that most research shows that migrants end up at the bottom of the ladder in the countries they move to, one might wonder why indeed they move at all. If the main motivation in migrating is to make a better life for themselves and their families, surely they would have been better off staying at home? Or would they? Can we prove that and, if so, how?

Data on 50,000 Turks

2000 Families: Migration Histories of Turks in Europe is a study led from the University of Essex involving an international team of researchers which is shedding a new and sometimes surprising light on the lives of migrants. By comparing the outcomes of migrants with their counterparts who chose not to migrate (rather than with the outcomes of natives in the receiving country), it is also offering a new and important perspective.

From the jobs they got to how they got on at school and university, their relationships with friends and family to their attitudes towards religion, marriage, gender and Turkish culture, the book provides a fascinating insight into the lives of the Turkish diaspora. In total the project has gathered information from some 50,000 participants.

Educational outcomes

Future articles will examine some of the other findings from the 2000 Familes study, but this article focuses on what an initial examination of the data tells us about educational outcomes for the study’s participants.

The unique design of the study allows researchers using the data to contribute to the debate on socio-economic outcomes of migrants and their children in two ways. First, they apply an innovative research perspective and include the context of origin. Second, because the dataset has information on family members of the same lineage in migrant and non-migrant families, they can compare the transmissions of resources over three generations in these two groups. This allows extended models exploring the effect of the parental socio-economic background on educational outcomes beyond the typical two-generation framework and determines the influence of grandparents’ socio-economic characteristics.

So the main question being asked was do migrants do better or worse educationally than their peers who stayed behind? The simple answer to that question is yes they do, but what the 2000 families data also shows which hasn’t been shown before is that while migrants, on the whole get better qualifications than their peers who stayed in Turkey, the gap between them has closed over time.

The research is also able to look at the links with the background of the child’s parents and grandparents, something often used by researchers to explain the gap in achievements between migrants and natives, but which, in isolation, doesn’t tell the whole story.

The 2000 Families data shows that the intergenerational transmissions of resources are weaker for migrants than non-migrants (which is in line with the findings of previous studies). However, given that Turkish parents in Europe did not have as high education as natives, the weak transmissions do not necessarily pose a real disadvantage.

The research looks at the descendents of the 1580 Turkish participants who migrated to Europe for work in the 1960s and 70s and 400 of their neighbours from the same regions who stayed behind (Generation 1). Once their children (Generation 2) and grandchildren (Generation 3) are included, the research had information on 23,000 individuals in total.

Participants were divided into 3 groups:

- Turkish born and educated

- Turkish born, but educated in the European Union

- Europe born and educated.

Those born in Europe and educated in Turkey were not included.

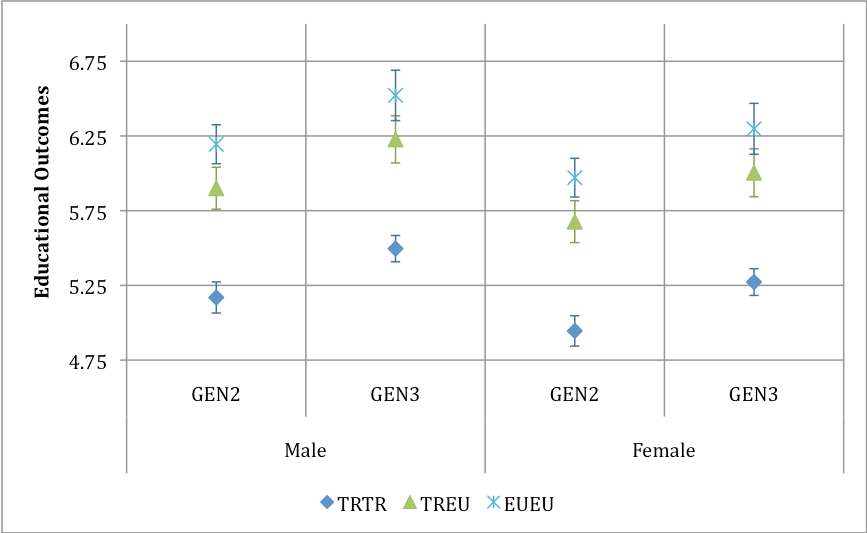

The Europe born and educated individuals had much higher educational outcomes than the Turkish born and educated participants. This was true for both second and third generation, although the gap was much smaller for the third generation. In other words, although individuals who completed their education in either Turkey or Europe have higher educational outcomes than the previous generation, the increase in educational outcomes in Turkey has been much greater than in Europe.

The educational advantage that migration once brought has lessened over time. It would seem that Turkey has ‘caught up’ or is catching up with Europe in terms of the educational opportunities it offers and this can explain the narrowing of the gap. However, those who were born and who completed their education in Europe are still doing better than non-migrant Turks. In line with the previous findings in the field, this reflects the better educational opportunities available in Europe compared to Turkey.

Migration as a rupture point

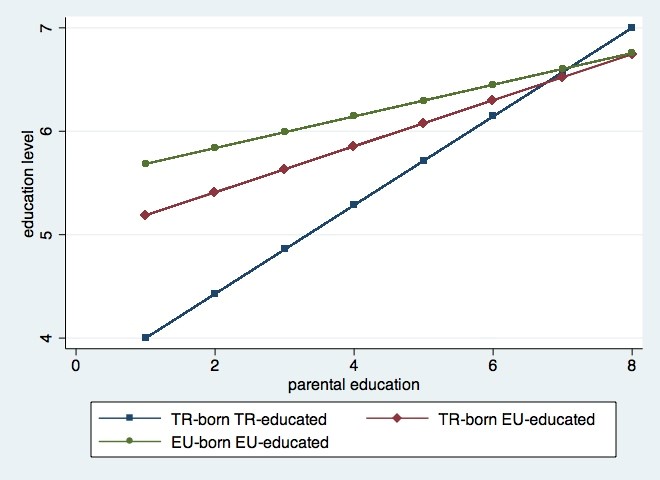

Parents’ education level and occupation were important factors for all the groups but less so for migrants, indicating a sort of ‘rupture’ point in the life course that weakens the links. Where a parent was also educated in Europe, there was no real influence on the education outcomes of the children. However, children from poorer backgrounds clearly benefited from the decision to migrate.

Figure 4.2: Educational outcomes of migrant groups and family generations by parental education

Source: 2000 Families Proxy Dataset, 2015

Socio-economic links over three generations were strongest where all had lived in Turkey. They were weakest where all three generations lived in Europe, once again indicating a sort of break point in the ‘inheritance’ of education and occupational status.

There was limited evidence of a stronger role for grandparents where the parents had a low socio-economic status.

Figure 4.4: Predicted outcomes for educational outcomes by family generation and migrant status

Source: 2000 Families Proxy Dataset, 2015

So it seems the descendants of Turkish economic migrants have secured better educational opportunities in Europe in spite of the cost migration brings, such as a possible lack of knowledge of the educational system, language problems or discrimination in the destination countries.

This is especially true for those from lower class families – the majority of Turkish migrants. Admittedly, as a result of the expansion of education in Turkey, non-migrant individuals are steadily improving their outcomes, but they have a long way to go before they catch up with their counterparts in Europe.

In other words, the decision to migrate has resulted in positive outcomes for the migrants’ descendants. Although multiple studies find they underperform compared to native groups in many destination countries, they are more educationally successful than their counterparts in Turkey. That said, the gap between migrant and non-migrant Turks is diminishing over time, possibly because of the rapid educational expansion in Turkey in recent decades. Therefore, whether people of Turkish descent in Europe will continue to enjoy educational gains from the migration decision remains an open question.

The 2000 Families Study data will be available to all researchers in 2016 and will be a fantastic resource for those genuinely interested in real evidence of how migrants benefit from the decision to leave their home and make a new life for themselves and their families in Europe.

Sait Bayrakdar is a researcher from the University of Essex. His main research interests are migration and ethnicity, social stratification, and socio-economic outcomes. This piece is a brief discussion of the results from his work on educational outcomes within the 2000 Families Study. The study begins with 2000 Turkish men born between 1920 and 1945 from five distinct regions in Turkey. It tracks the journeys to nine European countries of 1600 of them, following not just their lives, but the lives of their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren wherever they are in the world. It also follows the lives of some 400 hundred Turks who could have migrated but chose not to and compares their lives with those who left. Intergenerational consequences of migration: Socio-economic, family and cultural patterns of stability and change in Turkey and Europe, (Palgrave Macmillan 2016) present a range of initial findings from the data.