Liz Morrish (Nottingham Trent University)

In his Times Higher editorial in early February, John Gill wrote that higher education has been ‘weaponized’ as an issue for the forthcoming General Election. This outcome might now be contemplated ruefully by the nation’s vice-chancellors who, in future, might be careful what they wish for. After years of relative invisibility in the public sphere, mentions of universities in politics and the media are now as frequent as mentions of cricket. The optimists among us can congratulate ourselves that this signals a welcome democratization of higher education. Those with a glass half empty may point out that much of the publicity is damaging to the reputation of the sector.

Politicians from all quarters have charged universities with failing to address social inequality, failing to turn out employable graduates, failing to teach relevant courses, failing to prevent student radicalisation, failing to prevent illegal immigration, failing to give value for money, failing to tackle sexual assault on campus. Day after day, we learn that universities are failing, failing, failing. Indeed, only 38% of MPs think that universities spend money efficiently, according to a recent report. Despite the UK having one of the strongest higher education systems in the world, the signs do not augur well for universities in the inevitable review of spending after the 2015 election.

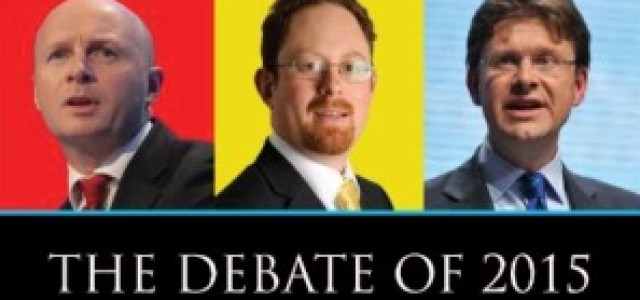

And so it was with great anticipation that on 2nd March I joined a sell-out crowd for the Higher Education Hustings sponsored by the Times Higher, HEPI, Universities UK and the Open University. This had to be among the most courteous of such events, historically. There was no bear pit heckling, just polite, if occasionally self-referential, questions from the floor. But then, this was Church House, Westminster, and a gathering of A List wonks including mission groups, think tanks and the occasional vice-chancellor. In a surreal postmodern trend, all of the hard core barracking was happening on Twitter. On the panel were politicians carrying the HE brief for each of the ‘main’ parties: Julian Huppert for the Liberal Democrats, Liam Byrne for the Labour Party, and Greg Clark for the Conservatives. The proceedings were tightly chaired by Baroness Martha Lane-Fox, Chancellor of the Open University, who seemed to be keeping tabs on the hashtag #HEhustings as unremittingly as she managed the politicians.

Fortuity had it that Labour had announced their policy on lowering tuition fees to £6000 just in advance of the event. However, this issue was not allowed to eclipse other pressing concerns for the sector, and questions on three more themes were invited: overseas students and immigration, research funding, and social mobility.

But tuition fees were the most urgent topic, and questions flew in from the floor. Liam Byrne vehemently argued that the current system has led to £280 billion being added to the national debt, a hole plugged currently by a bung from the Department of Business Innovation and Skills, and it is only a matter of time before the Treasury comes looking for its money back. The Labour policy, he claims, will represent a better deal for taxpayers, but it was judged regressive by Greg Clark, the current Minister for Higher Education, as it may favour only those high earning graduates who will end up paying back less money. However, as Andrew McGettigan has pointed out there are many reasons to seek to reduce students’ exposure to debt.

Vice-chancellors, though, probably care less about fee levels than about university funding generally. After three years of strong continuing student recruitment, they perhaps feel they have more reasons to put their faith in the stability promised by that line of credit, than to trust the government will not pull the plug on public spending in some future era of stringency. In that sense they are in harmony with Conservative thinking, but another view was put by Liam Byrne, that universities may benefit under the proposed Labour fee reduction, as this will entail a necessary restoration of at least some of the block grant from the government to compensate for the shortfall.

But vice-chancellors have another reason to be lighting candles for a Conservative election victory. A letter sent to The Times on 2nd February by their representative organisation, Universities UK, attempted to strangle the Labour fee policy even before it was announced. This defiance could be met by a swift settling of scores, if Labour are in government after May 7th. Vice-chancellors should have checked their privilege before casting their ballot so publically. We might be entertained by the spectacle of an immediate review of vice-chancellors’ remuneration, and the headlines in early March about the astounding heights that those salaries have reached since 2010 suggest this would have strong public support.

Julian Huppert is one Liberal Democrat whose seat is in danger at the election, so we might have expected some nervous allusions to his party’s aspirations to abolish tuition fees, overshadowed by mature regret about the impossibility of funding this. His new switch-and-bait was a line about getting rid of barriers to widening participation by funding a higher cost of living allowance: hey, who wants £15000? The addition of this multiplier to the escalating predictions of the RAB charge (loan write offs) did not unsettle him at all.

In contrast to the other higher education issues, the parties’ views about international students have been well known for some time. The Tory policy is dominated by Theresa May, and her insistence that non-EU students are counted in the (politically toxic) immigration figures. This was decried by both Labour’s Byrne and the Liberal Democrat Huppert. Perhaps Greg Clark had seen his predecessor David Willetts ousted for making a stand against the Home Office, but even so, he did not feel bound to oppose the more welcoming approach of Labour and the Lib Dems.

Research was skimpily dealt with by all three participants. It was essential for our science and innovation strategy, said Greg Clark. Science was excellent, and being done in excellent institutions. Excellence must be supported. “Will you support arts as well as science research”, interjected Baroness Lane-Fox? Absolutely. Huge contribution. Essential. The other two participants were rather let off the hook on the subject of research funding, and allowed to roam abstractedly over freedom of speech, where Julian Huppert emerged as rather a fundamentalist. When pressed about ring-fenced funding for STEM, Liam Byrne indicated there was a strong argument, but we need “a rational discussion”. It’s hard to decipher whether that is an endorsement, or code for “we would rather spend the money on earn-as-you-learn apprenticeships”.

Cheeringly, the debate roused a heckle from the floor when a former disabled student posed a question on the disappearing disabled students’ allowances. Greg Clark clearly wanted to unload the responsibility for supporting disabled students onto universities, without committing to funding this. The next question raised the shrinkage in mature and part-time students’ access to higher education. This, confessed Clark, was “not as well understood as it should be”. Martha Lane Fox declared her personal involvement in the issue as Chancellor of the Open University, which was recently hit by a 28% drop in numbers, and acknowledged that no party seemed to have a clear policy to prevent the shrinkage of that constituency.

And just as soon as the debate was catching fire, it was brought to a close. If Julian Huppert looked the most ill at ease of the three candidates, Greg Clark, as sitting Minister for Higher Education, was the candidate who lacked authority. My impression was that he must have been on one of those training courses where they teach you to use the language of the client group. His command of banalities, excellence, vision, sustainability, mirrored the lexicon of the average university strategy document (Sauntson and Morrish 2010). Martha Lane Fox relayed an accusation from Twitter that he was filibustering. I would have called it brain fade.

A show of coloured cards around the room indicated that the hustings had been a landslide to Liam Byrne. A seasoned commentator, and Assistant Vice-Chancellor of The University of Bolton, Patrick McGee, wrote on Twitter that it goes to show, despite modern theories of ‘presentation’, there really is no substitute for a candidate who has mastered the brief.

Reference:

Sauntson, Helen and Morrish, Liz. (2010). Vision, values and international excellence: The ‘products’ that university mission statements sell to students. In Molesworth Mike, Nixon, Elizabeth and Scullion, Richard (Eds). The Marketisation of UK Higher Education and the Student as Consumer. London: Routledge.

Liz Morrish is Principal Lecturer in Linguistics at Nottingham Trent University. Her research explores the discursive construction of sexual identity, and the growing area of critical university studies. With Helen Sauntson, she is co-author of New Perspectives on Language and Sexual Identity, Palgrave 2007. Her recent research has interrogated the kinds of academic subjectivity constructed by managerial discourse in British universities. Liz tweets @lizmorrish